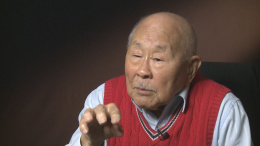

Fred Y. Hoshiyama

| Name | Fred Y. Hoshiyama |

|---|---|

| Born | December 7 1914 |

| Died | November 30 2015 |

| Birth Location | Livingston, California |

| Generational Identifier |

A Nisei community leader and career YMCA executive in San Francisco and Los Angeles, Fred Y. Hoshiyama was also a key figure in the history of the Japanese American National Museum and the Little Tokyo Service Center. Incarcerated at Tanforan and Topaz after graduating from the University of California, he was a fieldworker for the Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study (JERS) whose reports from those two camps provide glimpses of inmate life from his unique perspective.

Early Life

Yaichio Hoshiyama was born on December 7, 1914, in Livingston, California. (A schoolteacher gave him the name "Fred" when he was around six years old.) His parents, Yajuro and Fusatani Takato Hoshiyama, were immigrants from Niigata Prefecture. Yajuro came to the U.S. around 1900 and worked in an Alaska cannery and as a farm laborer, eventually saving money to invest in a farm with two others in Livingston's "Yamato Colony," the first of three Christian farm colonies started by Kyutaro Abiko , the publisher of the Nichibei Shimbun and a fellow Niigata kenjin. After marrying Tani—a marriage arranged in part by Yonako Abiko, the wife of Kyutaro—the couple bought their own farm in Livingston in Yaichio's name shortly after his birth. Five more children would follow, though only four including Fred—all boys—survived childhood. Tragedy struck again when Yajuro died of an intestinal ailment at the age of forty-seven in 1922, leaving Tani alone with four young boys. She struggled to run the farm for the next seven years, with the family coming close to starvation after the onset of the Great Depression in 1929. Yonako Abiko once again stepped in to help the family, introducing them to Hachiro Furuhata, who eventually married Tani and became a step-father to the four boys. The new family moved to San Francisco at the end of 1929. Hachiro worked as a collection agent for the Nichibei and later as an insurance agent.

The now teenaged Fred flourished in the city, attending Hamilton Junior High School and Commerce High School while working various jobs, including an arduous paper route for the Nichibei . Due to space constraints, Fred actually lived with the Abikos for the first year, doing chores around the house. Despite his work duties, he played basketball (despite standing just 5'2" tall), ran track and made the varsity tennis team. He also attended Sunday school every week, once going five years without missing a day. After graduating high school in 1933, he found a job with the Nippon Goldfish and Tropical Fish Co. and worked full-time helping to support the family for the next four years. He subsequently began attending San Francisco City College, earning an associates degree and went on the University of California in 1939, graduating in May of 1941 having majored in social psychology, social economics, and public administration. He supported himself by working as a live-in domestic worker. Upon graduation, he took a job as the boys' work secretary of the Japanese branch of the San Francisco YMCA. Working under Lincoln Kanai , Hoshiyama organized boys' activities including camping trips and sports leagues. He also taught Sunday school and continued to play tennis. Drafted prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor, he was rejected due to his poor eyesight.

With the outbreak of war, the Japanese YMCA became a center of community activity. Fred worked late nights helping families with future plans, helping them apply for relief and later, gathering supplies and equipment for use in the " assembly centers ." Initially angry and embittered by the exclusion orders, he wrote in a personal history for JERS, "I did think of staying put and was even willing to go to jail if necessary to fight for my rights and privileges which I cherished," though he eventually decided to accept and obey the government's decision. [1] Though he considered applying to graduate schools, he decided to be an early "volunteer" at Tanforan to help prepare the camp.

Wartime Incarceration and JERS Fieldworker

He drove to Tanforan in his own car on April 28, 1942, selling it to government for $40. He would eventually be placed in a horse stall with his mother and brothers. Though disgusted by conditions and by what he saw as the army's lack of preparation—"so many disgraceful mistakes were made," he wrote in his JERS personal history—he worked late nights to help inmates get settled and was eventually tapped by the administration to run the boys' recreational activities, given his YMCA experience. [2] After four months, he again volunteered to be part of the advance crew at Topaz, leaving on September 9 and arriving two days later. Upon arrival, he was recruited by Lorne Bell, a fellow YMCA staffer who was the camp's head of community services, to greet inmates as they entered the camp. "I was privileged to get to know the administration right away because they needed me to be the greeter," he wrote in his memoir. "Perhaps I was used, as that was another way of looking at it," he added. [3]

After working for Bell in community services and transferring to the welfare section a month later, he got word through the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council (NJASRC) that he had been accepted into a graduate program at Springfield College in Massachusetts that came with a scholarship, a guarantee of a job and additional funds for living expenses and travel. But needing additional funds to take the offer, he took a job at Topaz with Anderson, Doughty and Hargis, a plumbing contractor that was finishing up various plumbing systems at the camp, after having been tipped off by a friend. This job was an exceedingly rare one in that it allowed inmate workers to be paid at prevailing outside wages; even after reimbursing the War Relocation Authority (WRA) for room and board, Hoshiyama received some ten times the pay that inmates who worked for the WRA received. Inevitably, this arrangement generated significant resentment from other inmates. Though the work digging holes and installing pipes and fire hydrants was arduous, he made nearly $500 in the next two months despite injuries to both hands. He delayed his departure for Springfield, finally leaving on January 9, 1943, after four months at Topaz.

While at Tanforan, he was recruited by Dorothy Thomas to be a JERS fieldworker. During his incarceration at both Tanforan and Topaz, he wrote reports on various aspects of camp life, a detailed personal and family history, and kept a diary. "I didn't think much about the value of doing this, so I didn't do a good job," he told an interviewer in 2010. [4] Historian Brian Hayashi wrote that reports by Hoshiyama and his Berkeley classmate Doris Hayashi "were less informative in part because the two were too preoccupied with their own personal lives to observe carefully their subjects," and indeed Hoshiyama's diary is filled with concerns about making money for graduate school, his AD&H work, and his dating life. But Hayashi added that Hoshiyama's "observations of political factions in Tanforan proved priceless...." [5] Hoshiyama's observations of Topaz's first month or so are also candid and insightful. Once he began the job with AD&H, his JERS work beyond his diary largely ended.

Postwar Life and Career

Though initially miffed that Springfield put him in an international dorm—"I thought it was kind of interesting that I was put among the 'foreigners,' even though I was a U.S. citizen...," he wrote in his memoir—he had a good experience there and graduated with a master's degree in 1944. [6] But despite the help of sympathetic faculty members, he was unable to land a job beyond menial positions. Receiving an offer of a scholarship at Yale Divinity School, he thus took it. He was there for only a short time, though, when a former Springfield classmate, Henry Koizumi, told him about a YMCA job opening in Honolulu. When he got to Honolulu in September 1945, he discovered that Lorne Bell, his old boss at Topaz, would be his supervisor. In late 1946, he was offered a job heading the Japanese YMCA in San Francisco, but was enjoying his life in Hawai'i so much that he turned it down initially. But upon further reflection, he decided there was a greater need there, and he took the position, returning to San Francisco in January 1947. He oversaw the transition to the non-segregated Buchanan Street YMCA-YWCA Center, and over the next decade saw his responsibilities increase with three additional branches coming under his supervision. During this period, he also marred Irene Sumiye Matsumoto in 1948, whom he had met at a YMCA dance. The couple had a son and a daughter.

Fired in 1967 after a change in leadership at YMCA, he was later reinstated and became part of the national staff based in Los Angeles as part of the Urban Action and Development group that focused on urban problems and at-risk youth. In this capacity, he ran the program that he became best-known for, the National Youth Program Using Minibikes (NYPUM). Leveraging connections with the Japanese American Citizens League and with Honda, he expanded the program to serve over half a million youth in its first ten years. He retired from the YMCA in 1980. In retirement, he became one of the founders of and a key fundraiser for the Japanese American National Museum and served as a board member of the Little Tokyo Service Center for twenty-seven years. Among his many honors are an honorary doctorate from Springfield College, induction into the YMCA Hall of Fame, the naming of the YMCA Asian Leadership Network scholarship as the "Fred Y. Hoshiyama Scholarship Fund." After a gala 100th birthday celebration at the Japanese American National Museum in 2014, Hoshiyama passed away a few days before his 101st birthday on November 20, 2015.

For More Information

Densho interview with Fred Hoshiyama by Tom Ikeda, February 25, 2010.

Hoshiyama, Fred Y. and Doug Nakashima. Pearls: The Fred Y. Hoshiyama Story . Edited by Craig Altschul. Chicago: Marshall Jones Company and YMCA Asian Leadership Network, 2010.

JERS Highlights

Many of the documents Fred Hoshiyama wrote as part of the JERS project are available online as part of The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement: A Digital Archive collection at the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. Some of the collection highlights (with the Bancroft call number noted) are below.

Tanforan: Population and Composition , BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder B8.23. [Report on various aspects of Tanforan, including the demographics of its population, administration, economic organizations, and employment. 28 pages.]

Political Activity at Tanforan , BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder B8.25. [Covers both the political groupings of the inmates and political activity at Tanforan. 41 pages.]

Family History and Autobiography , BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder B12.35. [Written mostly at Tanforan in August and September 1942. 103 pages]

JERS related correspondence , BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder B12.40. [June 22 to Sept. 20, 1942. 22 pages.]

Fred Y. Hoshiyama Diary, October 2 to December 9, 1942 , BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder H9.04. [65 pages.]

Miscellaneous Topaz reports , BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder H9.06. [Various reports and observations from the first two months of the camp including profiles of white staff and pieces on recreation, religion, delinquency, and various other topics. 80 pages.]

JERS related correspondence , BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder W 1.09. [August to November '42. 36 pages.

Footnotes

- ↑ Fred Hoshiyama, Personal History, [1942], p. 1l, The Japanese American Evacuation the Resettlement: A Digital Archive, Bancroft Library, University of California (JAERDA) BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder B12.35, accessed on June 27, 2020 at http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_b024b12_0035.pdf .

- ↑ Hoshiyama, Personal History, 7.

- ↑ Fred Y. Hoshiyama, Pearls: The Fred Y. Hoshiyama Story , as told to Doug Nakashima, edited by Craig Altschul (Chicago: Marshall Jones Company and YMCA Asian Leadership Network, 2010), 22.

- ↑ Fred Y. Hoshiyama interview by Tom Ikeda, Segment 23, Culver City, California, Feb. 25, 2010, Densho Visual History Collection, Densho Digital Archive, http://ddr.densho.org/media/ddr-densho-1000/ddr-densho-1000-275-transcript-f825bde443.htm .

- ↑ Brian Masaru Hayashi, Democratizing the Enemy: The Japanese American Internment (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004), 297.

- ↑ Hoshiyama, Pearls , 30.

Last updated Nov. 3, 2020, 10:25 p.m..

Media

Media