Harold Ickes

| Name | Harold Ickes |

|---|---|

| Born | March 15 1874 |

| Died | February 3 1952 |

| Birth Location | Hollidaysburg, PA |

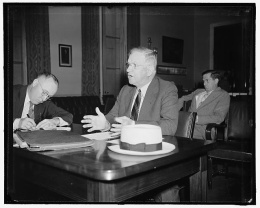

As secretary of the interior from 1933 to 1946, Harold Ickes (1874–1952) was a key architect of liberal principles through the depression and World War II. A staunch advocate for civil rights, he opposed the mass exclusion and incarceration of Japanese Americans, and, after the War Relocation Authority came under his management in 1944, was one of the most outspoken advocates for ending exclusion to the West Coast and for fair play for Japanese Americans.

Early Life

Harold LeClair Ickes was born on March 15, 1874, in Hollidaysburg, Pennsylvania, to Jesse Boone Williams Ickes and Matilda "Mattie" McCune. The family moved to Altoona, Pennsylvania, shortly after his birth, where his father was a salesman and accountant. His mother's death from pneumonia in 1890 when Harold was a teenager dramatically changed his life; he and his sister were subsequently sent to live with an aunt and uncle near Chicago. Given little support by his father, he worked long hours at his uncle's drug store for room and board. Despite the difficult conditions, he was senior class president and valedictorian when he graduated high school in 1892.

He worked his way through the University of Chicago, graduating in 1896, and took a job as a newspaper reporter. He went to law school at the University of Chicago, graduating with a law degree in 1907 and working as a lawyer subsequently. During this time, he became involved in Chicago politics, managing the mayoral campaign of John Harlan in 1903 and becoming active with the Progressive wing of the Republican Party. He subsequently served as Theodore Roosevelt's Cook County campaign manager during his unsuccessful 1912 presidential bid. Ickes also served overseas with the YMCA during World War I.

Married in 1911 to Anna Wilmarth Thompson, he managed his wife's successful campaigns for the Illinois General Assembly in 1928, 1930 and 1932. In 1932, he headed a Western Independent Republican Committee for Franklin D. Roosevelt and upon FDR's election, was appointed secretary of the interior.

Secretary of the Interior

Ickes served as secretary of the interior for thirteen years, the entirety of FDR's presidency. In this capacity, he managed some 30,000 employees and oversaw the governments of Hawai'i, Alaska, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, and the Philippines (after 1934) among other possessions. His charge also included the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the Civilian Conservation Corps, and the Public Works Administration, which he personally directed. His administration of the PWA's $6 billion of construction projects over six years without a hint of impropriety earned him the nickname "Honest Harold." He was also noted for his commitment to conservation and his enlargement of the National Park Service.

Ickes was also had a notable civil and human rights record. He was one of the first in the administration to speak out on Nazi atrocities in Europe and promoted civil rights for African Americans. Under his watch, the Department of Interior was desegregated, and he appointed the first African American federal judge, William Hastie in 1937. Ickes also played a key role in arranging Marion Anderson's influential 1939 performance on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

He was known for his hot temper and repeatedly clashed with agriculture secretary Henry Wallace, Work Projects Administration head Harry Hopkins and often with FDR himself, offering numerous resignations that were not accepted. Yet he became one of the President's closer advisers and was a tireless and effective campaigner in his various reelection bids.

His wife Anna was killed in an auto accident in 1935, and he remarried in 1938 to Jane Dahlman, a woman nearly forty years his junior. The couple had two children, Harold, Jr. (born 1939) and Elizabeth (1941) and operated a working farm in Maryland. Already in his late 60s as the war approached, he was by all accounts happy in his personal life, but burdened with a bad heart and "problems with whisky and barbiturates." [1]

War and Japanese Americans

Though he played a background role in the decision to remove all Japanese Americans from the West Coast, he personally disagreed with that decision. Calling the camps "fancy-named concentration camps" in his diary, he noted shortly after Executive Order 9066 that mass exclusion was "both stupid and cruel. At vast expense and with a total disregard of any considerations due any Japanese, these people will be torn from their homes and transported to inland camps, there to be maintained by the Government until drum-head court martials shall decide whether it is safe for them to return." [2] Having oversight over the governance of Hawai'i, Ickes also pushed unsuccessfully to loosen military rule over the islands starting in 1942.

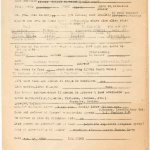

In the spring of 1943, Ickes and his wife hired four Japanese Americans who had been incarcerated at Poston to work on their farm, in part to boost support for resettlement and in part because they need the labor. He also wrote to the President expressing his concerns about the continuing incarceration embittering Nikkei in the camps who would otherwise be "well-meaning and loyal." [3]

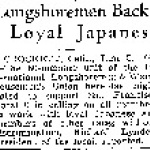

Since unrest in the incarceration camps at the end of 1942, the War Relocation Authority had come under sometimes withering attack by anti-Japanese agitators. By the end of 1943, Attorney General Francis Biddle advised the President that the WRA would be better off under the wing of some larger department. Given his prior support of Japanese Americans, he reluctantly agreed to take on the WRA within the Department of Interior. At his first press conference afterwards, he defiantly faced the critics, calling their statements "vindictive, bloodthirsty onslaughts of professional race-mongers." [4]

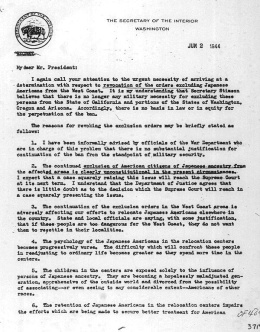

For much of 1944, Ickes pushed to allow Japanese Americans to return to the West Coast, working both internally to convince the War Department and the president and externally to denounce anti-Japanese activists on the West Coast. In an April 1944 speech in San Francisco, for instance, he praised the work of the WRA and characterized opponents as wanting it to become a "lynching party" and that "to do this would be to lower ourselves to the level of the fanatical Nazis and Japanese warlords. Civilization expects more from us than from them." [5] He continued to speak out in favor of Japanese Americans after the West Coast was finally opened to Japanese Americans at the end of 1944.

After the War

Ickes lobbied President Harry Truman for consider legislation to redress Japanese Americans for property losses due to exclusion. Such legislation—the Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act —would eventually pass in 1948. Ickes resigned from office in February 1946 after a dispute with Truman, ending his thirteen-year run as secretary of the interior.

In retirement, he continued his voluminous diary—eventually edited by Anna and published in part—and worked as a columnist for the New York Post and New Republic . He died on February 3, 1952.

For More Information

Robinson, Greg. By Order of the President: FDR and the Internment of Japanese Americans . Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001.

Watkins, T. H. Righteous Pilgrim: The Life and Times of Harold L. Ickes, 1874–1952 . New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1990.

White, Graham and John Maze. Harold Ickes of the New Deal: His Private Life and Public Career . Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1985.

Footnotes

- ↑ Graham White and John Maze, Harold Ickes of the New Deal: His Private Life and Public Career (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1985), 222.

- ↑ T. H. Watkins, Righteous Pilgrim: The Life and Times of Harold L. Ickes, 1874–1952 (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1990), 792.

- ↑ The four were brothers Fred, Roy and Joseph Kobayashi, along with Barbara Kobayashi, wife of Fred. Pacific Citizen , April 22, 1943, p. 3; Watkins, Righteous Pilgrim , 793.

- ↑ Ibid., 795.

- ↑ Kevin Leonard, Battle for Los Angeles: Racial Ideology and World War II (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2006), 234.

Last updated June 19, 2020, 4:07 p.m..

Media

Media