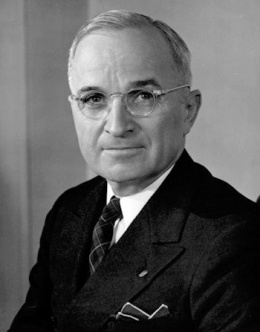

Harry S. Truman

| Name | Harry S. Truman |

|---|---|

| Born | May 8 1884 |

| Died | December 26 1972 |

| Birth Location | Lamar, Missouri |

Harry Truman (1884-1972), 33rd President of the United States, was in office during the final exodus of Japanese Americans from the camps. A strong supporter of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, Truman helped push for enactment of evacuation claims legislation to atone in part for mass confinement.

Early Life

Harry S. Truman (he had no middle name beyond the initial) was born in Lamar, Missouri, on May 8, 1884, the first of three children of John Anderson Truman, a farmer, and Martha Ellen Truman. After spending his early years in a variety of locations, Truman moved to Independence, Missouri, with his family in 1890, and spent his childhood there. A sickly, bespectacled boy and a self-proclaimed "sissy," Truman read widely and studied piano. In 1902, after completing high school, Truman moved to Kansas City, where he worked as a bank employee. In 1906 he moved to Grandview to help operate the family farm.

In 1917, Truman helped organize the 2nd regiment of Missouri Field Artillery. After being absorbed into the 129th Field Artillery Unit, the unit was sent to France. Truman was promoted to captain and assigned command of Battery D. He served with the unit in action in France during World War I, notably at the Meuse-Argonne campaigns.

Upon his return home in 1919, Truman married Elizabeth "Bess" Wallace, a childhood friend, and opened a haberdashery business in Kansas City. The business soon failed, however, and Truman would spend years paying off his accumulated debt. Through the intervention of an army buddy, Truman was taken up by Tom Pendergast, the powerful "boss" of the Pendergast political machine that dominated Kansas City politics. With the support of the machine, Truman was elected as a judge of the Jackson County Court (an administrative position) in 1922, and twice re-elected.

Rising Political Fortunes

In 1934, Truman was elected U.S. Senator from Missouri. While his personal honesty was unquestioned, his complete reliance on the corrupt machine for political support led him being dubbed "The Senator from Pendergast." After an undistinguished first term, Truman managed to win re-election in 1940, despite the collapse of the Pendergast machine and President Franklin D. Roosevelt's refusal of support. During his second term, Truman gained national renown due to his founding and direction of the Senate Special Committee to Investigate the Defense Program (widely known as the "Truman Committee"). The committee investigated incidents of fraud and waste in the defense program and was credited with saving taxpayers billions of dollars. Truman had little contact with Japanese Americans during this period.

At the Democratic National Convention in July 1944, Truman was pushed by party political leaders, notably Robert Hannegan, as a popular vice presidential candidate—the party chiefs considered the existing vice president, Henry Wallace, too liberal, while the other main candidate, former senator and Supreme Court Justice James Byrnes, was a Southerner whom they considered too unpopular with labor unions and progressives. President Roosevelt accepted Truman (dubbed "the second Missouri Compromise") as his running mate, but excluded him from policy deliberations. After Truman was elected vice president in November 1944, he hardly saw Roosevelt.

On April 12, 1945, Roosevelt died of a cerebral hemorrhage, and Truman became president. Although he had virtually no preparation for the presidency, he led the government in the months that followed, as World War II reached its final stages. Truman accepted the surrender of Nazi Germany, and met with Soviet leader Joseph Stalin and British Prime Ministers Winston Churchill and Clement Attlee at the Potsdam Conference in July 1945. Most notably, it was Truman who made the final decision to proceed with the mass bombing of Tokyo and other Japanese cities during mid-1945, and ultimately the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945. Japan's surrender in September 1945 ended World War II. Truman later publicly asserted that he had no regrets over the bombing, which he considered necessary to end the war.

Civil Rights and Japanese Americans

With the end of the war, Truman was confronted by conflicts over inflation, labor strikes, health care, and especially racial justice for African Americans. To help resolve problems of racial discrimination, in 1946 Truman created the President's Committee on Civil Rights. In fall 1947, the Committee delivered its report, To Secure These Rights , recommending various federal government actions to promote equal rights. In February 1948, with an eye both on principle and on attracting liberal votes in that year's presidential election, Truman sent a message to Congress in which he proposed a series of civil rights laws based on the report. Congress, controlled by a coalition of Republicans and conservative Southern Democrats, refused to enact them. Blocked in Congress, Truman used his presidential powers where he could, issuing executive orders desegregating the federal government bureaucracy and integrating the U.S. armed forces. He also authorized the Justice Department to intervene as amicus curiae in favor of civil rights in a series of cases before the U.S. Supreme Court.

It was in the context of civil rights that the Truman Administration became involved with Japanese Americans. In December 1945, Eleanor Roosevelt sent the President letters with information about the terrorism and discrimination by white vigilantes in California against returning Issei and Nisei . Shocked by the reports, Truman responded, "These disgraceful actions almost make you believe that a lot of our Americans have a streak of nazi in them." [1] Truman asked his attorney general, Tom Clark , whether the federal government could either prosecute the vigilantes or oblige California state authorities to provide protection, and added, "It certainly makes me ashamed." When Clark responded that the federal government generally lacked authority to act, Truman ordered him to take whatever action he could. [2] Aside from his disgust over the violence, Truman (himself the first army veteran in the Oval Office in two generations) was motivated by admiration for the exploits of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team . In February 1946, he sent a message to the first postwar convention of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) to pay tribute to the Nisei soldiers. "Their service is a credit not only to their race and to America, but to the finest qualities in human nature." [3] When the 442nd returned from overseas in July 1946, Truman reviewed the unit in a ceremony at the White House, and in a speech told the veterans, "You fought not only the enemy, but you fought prejudice—and you have won." [4]

In the wake of his speech to the Nisei soldiers, Truman offered his personal support to the efforts of the Department of the Interior to secure evacuation claims legislation. In July 1946 Truman sent public letters to the heads of the Senate and House Judiciary Committees, calling passage of the claims bills, "A task that, in all good conscience, should be done if the government is to accord justice to those of its people who, during the war, were dealt with so harshly." [5] After the bills were defeated, Truman's minority advisers Philleo Nash and David Niles worked with JACL staffer Mike Masaoka to line up support, while the President's Committee on Civil Rights not only proposed evacuation claims legislation in To Secure These Rights , but supported laws barring discrimination based on national origin and called for an inquiry into the entire wartime confinement policy, which the report termed "the most striking mass interference since slavery with the right to physical freedom." [6]

When President Truman sent his proposed civil rights legislation to Congress in February 1948, among the reforms was evacuation claims legislation. In his civil rights message to Congress, Truman again underlined the importance of the legislation, noting that Japanese Americans had been removed "solely because of their racial origin" (significantly, the President provided no justification on the ground of military security) and had suffered property loss through no fault of their own. [7] In July 1948, the Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act passed—the only part of Truman's civil rights program to be enacted by Congress. Sadly, for many Japanese American families, the law would prove to be a slow and ineffective means of obtaining restitution, a problem made worse by the adversarial position of the Justice Department.

The Truman Administration found other ways to support equal rights of Japanese Americans. In Spring 1948, with the blessing of the president, Attorney General Tom Clark submitted an amicus curiae brief in the Supreme Court case of Takashashi v. California Fish and Game Commission , opposing California's anti-Asian fishing law as a violation of the 14th Amendment. Truman also supported statehood of the Territory of Hawai'i, with its large ethnic Japanese population, and amendments to existing immigration legislation to provide at least token entry for Japanese and to make it possible for Japanese immigrants to naturalize. Though these provisions were absorbed into the McCarran-Walter Act , Truman vetoed that bill because of other, more repressive elements. While many progressive Nisei hailed Truman's veto, JACL agents bent on securing Issei immigration and naturalization lobbied Congress to override the president's veto, and the bill was enacted in summer 1952.

Cold Warrior and Legacy

Harry Truman, who had trailed in the polls during much of the 1948 presidential campaign, surprised many commentators when he won reelection in November 1948. During his second term, however, he grew less concerned with Japanese Americans as his presidency became increasingly dominated by the growing military and ideological conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union known as the Cold War. Already, beginning in 1947, Truman's administration had offered military aid to Greece and Turkey, fighting Communist-led insurgencies, as part of the "Truman Doctrine." The Truman administration also proposed the Marshall Plan to help finance European postwar recovery, and preserve democratic institutions. In 1949, the United States became a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, the nation's first-ever peacetime military alliance. To further mobilize forces against the perceived Soviet threat, Truman signed the National Security Act of 1947, which merged the military services into the Department of Defense, and created the National Security Council and the Central Intelligence Agency. (It also established the Loyalty-Security Program for testing federal employees, an action that would help fuel the anti-Communist hysteria of the McCarthy period). Following the North Korean invasion of South Korea in June 1950, Truman mobilized American troops under the command of General Douglas MacArthur under the aegis of the United Nations, thus fighting an undeclared war. The war ultimately resulted in a two-year standoff that sharply reduced Truman's popularity. Although eligible for re-election, he chose not to run for a third term.

After leaving the White House in January 1953, Truman returned to his hometown of Independence. There he wrote his memoirs and assisted the setting up of the Truman Library. He died in December 1972, following a long illness. While he was not generally well regarded during his presidency, his historical reputation has grown considerably since his death. In the same way, his position as a warm supporter of Japanese Americans has added to his overall stature as a civil rights president.

For More Information

Hosokawa, Bill. JACL in Quest of Justice . New York: William Morrow, 1982.

Nakasone-Huey, Nancy Nanami. "In Simple Justice: The Japanese-American Evacuation Claims Act of 1948." Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Southern California, 1986.

Robinson, Greg. A Tragedy of Democracy: Japanese Confinement in North America . New York: Columbia University Press, 2009.

Footnotes

- ↑ Letter, Harry Truman to Eleanor Roosevelt, December 21, 1945, Eleanor Roosevelt correspondence file, Harry S Truman Library, Independence, MO (henceforth HSTL).

- ↑ Letter, Harry Truman to Tom Clark, December 21, 1945. Tom Clark Papers, HSTL. Harry Truman, memorandum to the Attorney General, January 17, 1946. President's Secretary's File, 197, HSTL.

- ↑ Harry Truman, "Statement to the Japanese American Citizens League," February 7, 1946, reprinted in "Pres. Truman Sends Special Greetings to Nisei Convention," Utah Nippo , February 18, 1946.

- ↑ Harry Truman, "Remarks Upon Presenting a Citation to a Nisei Regiment," July 15, 1946, Public Papers of the Presidents, Harry S. Truman , accessed on March 18, 2014 at https://www.trumanlibrary.org/publicpapers/index.php?pid=1666&st=&st1=

- ↑ Letter, Harry Truman to Sen. Pat McCarran, July 22, 1946, PSF 6-Y, HSTL.

- ↑ U.S. Government. President's Committee on Civil Rights, To Secure These Rights: Report of the President's Committee on Civil Rights (Washington DC, Government Printing Office, 1947), 30-31.

- ↑ Harry Truman, Special Message to the Congress on Civil Rights, February 2, 1948, in Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Harry Truman: Containing the Public Messages, Speeches and Statements of the President: Vol. 3,1948 (Washington D.C. Government Printing Office, 1966), 121.

Last updated July 7, 2020, 7:49 p.m..

Media

Media