Jiro Onuma

| Name | Jiro Onuma |

|---|---|

| Born | February 2 1904 |

| Died | June 27 1990 |

| Birth Location | Kanegasaki, Iwate Prefecture, Japan |

| Generational Identifier |

Jiro Onuma (1904-90) was a gay Japanese American born on February 2, 1904, in Kanegasaki, Iwate Prefecture, Japan. In 1923, he immigrated to the United States and spent most of his adult life in the San Francisco Bay Area. His collection of personal materials, held at the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society archive, is one of their few archival collections documenting the lives of LGBTQ Japanese Americans. It consists of photographs, personal documents, and an assortment of male homoerotic ephemera. It also contains rare photographs of adult gay Issei taken in the American concentration camps.

Jiro Onuma and Same-Sex Intimacy among Japanese Americans

The scarcity of wartime accounts of Japanese American same-sex intimacy and sexuality may be related to the unusual organization of the incarceration camps. Unlike most prison facilities that are gender segregated, the American concentration camps organized inmates by family unit, housing up to six family members in a single horse stall or barrack space. Silence around same-sex relationships may also relate to internal pressure within Japanese American communities to assimilate by conforming to American norms of heterosexuality. [1] During World War II, this pressure to conform was heightened especially among some Nisei men, who sought to prove their masculinity and loyal citizenship by disavowing homosexuality or enlisting in the highly decorated 442nd Japanese American combat team. [2]

Onuma was 19 years old when he and his father boarded the Shinyo Maru steamship in Yokohama headed for San Francisco in 1923. His father, Kogoro Onuma, was already working for a laundry in Coalinga, California, and he returned to Japan to accompany his son's journey. Within six months of Jiro Onuma's arrival, the possibility that the rest of his family might move to California was denied by the passage of US federal law prohibiting Japanese immigration.

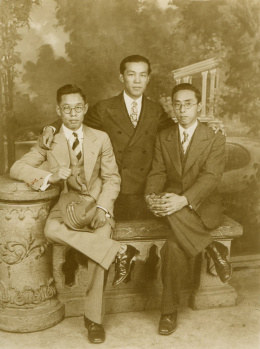

By 1932, Onuma was working in the present-day Tenderloin district of San Francisco as a laundry machine presser for Mercury Laundry and Cleaners, where he and a dozen other Nikkei laundrymen also rented rooms. During the prewar era, Onuma took numerous photographs with his Japanese American male friends and lovers dressed up for professional portraits at the Moriyama Studio in Japantown or posed casually together in and around San Francisco.

Onuma was an avid collector of homoerotic male physical culture ephemera and magazines. He owned a postcard displaying a matador with a bronze erect penis that could be detached and used as a necktie clip. Onuma was especially fond of Earle Liederman, a professional body builder who promised to make his clients muscular in twelve weeks through his mail-order correspondence school. [3] Onuma collected scores of Liederman keepsakes and put together an intimate photo album devoted exclusively to his beloved muscular icon.

World War II Incarceration

In 1942, Onuma spent five months confined in San Bruno, California, at the Tanforan Assembly Center , where U.S. authorities imprisoned nearly 8,000 Japanese Americans inside a racetrack complex hastily converted to house inmates in whitewashed horse stables, converted grandstands, and quickly constructed barracks in the infield area. According to Onuma's WRA case file, Tanforan authorities did not even issue Onuma a cot and straw tick mattress to sleep on until twenty-five days after his arrival. [4]

On September 11, 1942, the federal government transported Onuma to Topaz concentration camp in central Utah. [5] As a 38-year old single bachelor, Onuma could have been housed in the bachelor's quarters. However, he was placed in Block 3, Barrack 5, Unit B, with Topaz baseball star Masao Akagaki and his mother Fuku Nishi. Akagaki's father had been arrested by the Justice Department in 1942 and held in custody in Santa Fe until his entire family was confined in the Alien Enemy Detention Center Facility in Crystal City, Texas.

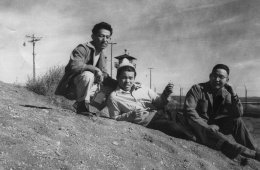

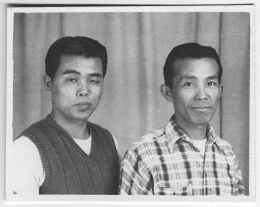

Onuma's collection contains three photographs taken while he was imprisoned at Topaz. The first is a group portrait showing Onuma and his workmates from the Block #3 Mess Hall. The second photograph shows Onuma and his boyfriend Ronald (last name unknown). It is quite possible that his portrait was taken at the cooperatively run Topaz Photo Studio in the summer of 1943, shortly before Ronald and their Kibei friend Sakae Sasaki were sent to Tule Lake , the high security concentration camp redesignated as a " segregation center " for "disloyal" inmates. [6] In spring 1943, pro-administration forces used fear tactics and shame to urge inmates to change negative responses to questions 27 and 28 of the " loyalty questionnaire ." [7] Onuma initially answered "no" to both questions, but four weeks later he filed to change his answer to question 28, thereby enabling him to remain at Topaz until his release on May 19, 1944. [8] Although Onuma did not go to Tule Lake with his friends and lover, he did receive a photograph of Ronald, Sasaki, and another man at Tule Lake showing barbed wire and a guard tower in the distance. [9] Onuma's wartime pictures might be the only known photographs of adult gay Issei in the American concentration camps.

Postwar and Legacy

Upon his release from Topaz, Onuma was placed in a menial job washing floors at St. Marks Hospital in Salt Lake City, Utah. He quit after four days of demeaning labor and was unable to find other employment in the area. Onuma moved to Denver, Colorado, where he lived for two years and worked at Navarre Café as a bus boy. By 1951, Onuma was back in San Francisco working at Pine Street Laundry in Japantown. On August 29, 1956, Onuma became a naturalized citizen of the United States. Later in life, Onuma worked as a housekeeper and traveled extensively in Asia and Latin America.

During the last ten years of his life, Onuma befriended Peter Mycue (1938-99), a single man who had spent time in Japan during his military service and enjoyed singing musical show tunes from memory. According to Mycue's gay brother Edward, Jiro was clearly in love with Peter even though this love remained unrequited during their many years of friendship and companionship. [10]

Onuma had no other family or relatives in the United States. On June 27, 1990, at age 86, Onuma died alone in his spare studio apartment in a building known as the Lone Star Hotel. Edward Mycue found his body many days after his death. Within hours of this discovery, Onuma's apartment was robbed and stripped of its valuables while his body was still in the room. In his last will and testament, Onuma left half of his modest estate to Peter Mycue and half to Kimochi, a nonprofit caregiving organization primarily serving Japanese American seniors. In 2000, Edward Mycue and his partner Richard Steger gifted Onuma's materials to the GLBT Historical Society. Although Jiro Onuma was not a prominent figure in LGBT or Japanese American communities during his lifetime, the dual legacies that he honors in his last will and testament appear remarkable today amidst the scarcity of queer Japanese American wartime images, stories, and memories.

For More Information

Howard, John. Concentration Camps on the Home Front: Japanese Americans in the House of Jim Crow . Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2008.

Takemoto, Tina. "Looking for Jiro Onuma: A Queer Meditation on the Incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II." GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 20.3 (2014): 241-275.

Footnotes

- ↑ Tina Takemoto, "Looking for Jiro Onuma: A Queer Meditation on the Incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II," GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 20.3 (2014): 241-275.

- ↑ Greg Robinson, "The Great Unknown and the Unknown Great: Nikkei Activists, History and Homophobia," Nichi Bei Times Weekly (June 18-24, 2009).

- ↑ For a discussion of the homoerotism of male physical culture see Michael Anton Budd, "Every Man a Hero," in The Passionate Camera: Photography and Bodies of Desire , ed. Deborah Bright (London and New York: Routledge, 1998): 41–57.

- ↑ Jiro Onuma Case File, War Relocation Authority, Record Group 210, National Archives (hereafter cited WRA RG 210, NA).

- ↑ Jiro Onuma Case File, WRA RG 210, NA.

- ↑ "Photo Service for Residents," Topaz Times , May 20, 1943, 2; "Departure Order Set for Tule Lake Bound," Topaz Times , August 24, 1943, 1.

- ↑ WRA set June 1, 1943, as the last date for cancelling requests for repatriation and changing responses to questions 27 and 28. "Directors Plan Meeting to Discuss Segregation," Topaz Times , July 15, 1943, 1.

- ↑ Jiro Onuma Case File, WRA RG 210, NA.

- ↑ Takemoto, "Looking for Jiro Onuma, 260-264. See John Howard, Concentration Camps on the Home Front: Japanese Americans in the House of Jim Crow (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2008); 117.

- ↑ Edward Mycue and Richard Steger (donors of the Onuma Collection, GLBT Historical Society), interview with author, January 17, 2011.

Last updated June 22, 2020, 7:16 p.m..

Media

Media