No-no boys

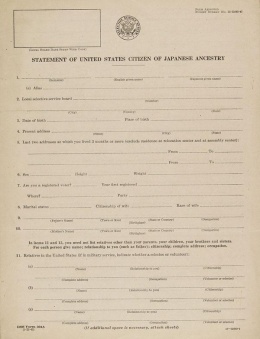

Colloquial term for those who answered "no" to questions 27 and 28 , the so-called "loyalty questions" on the Application for Leave Clearance form (aka the loyalty questionnaire .) As part of the segregation of the "loyal" and the "disloyal," the no-no group were moved to Tule Lake . Though stigmatized as "disloyal," the no-noes had a wide variety of reasons for their actions. No-no status was stigmatized after the war, and many have remained reluctant to tell their stories.

In the winter of 1943, the War Relocation Authority launched their loyalty questionnaire in an attempt to segregate the "loyal" and the "disloyal." Though the vast majority eventually answered the key loyalty questions affirmatively, a significant minority either refused to answer, gave qualified answers, or answered negatively—about 12,000 out of the 78,000 people over the age of seventeen whom the questionnaire was distributed to. [1] People who answered in any of these manners were considered "disloyal" and were ultimately segregated at Tule Lake . (See segregation .) Though not all of them technically answered "no" to questions 27 and 28, the adult male portion of what the WRA called "segregees" became synonymous with the "no-no boys" in the years after the war.

Further complicating matters is the fact that the term "no-no boys" has often been used to refer to Japanese American draft resisters over the past two or three decades. [2] Some of this confusion may be due to the classic novel No-No Boy by John Okada. Largely ignored upon its initial publication in 1957, it was rediscovered in the 1970s and has been twice republished and widely read since then. In that book, the characteristics of both the "segregees" and the draft resisters are conflated in the lead character, a young man who answers "no" to the loyalty questions and is sent to prison for refusing military service. While many draft resisters did go to prison, they generally answered the loyalty questions "yes-yes"; those who answered them "no-no" were mostly segregated at Tule Lake, but were not imprisoned (at least not outside of Tule Lake).

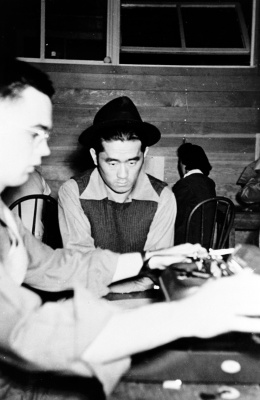

The conflation of the no-no boys and the draft resisters was no doubt encouraged by their common postwar experience. Both groups were largely shunned by a Japanese American community that emphasized loyalty and military service after the war. As essayists Gary Tachiyama and Roland Kotani explained, "Those who answered 'no' to both questions 27 and 28 the 'no-no boys'—were castigated by the Japanese American community and the broader public as being disloyal traitors to the United States." [3] Both groups were also embraced by mostly younger community activists in the 1970s looking for those who resisted the mass incarceration and as part of the lead up to what would become the redress movement. At the July 1977 dedication of a commemorative plaque at site of the Tule Lake camp, Ben Takeshita stated that "up to ten years ago, I would not have told anyone where I learned my Japanese nor would I have admitted that I had been at Tule Lake as a 'No-No.'" He added that he now felt "comfortable enough to admit" that "some of us were indeed No Nos and others were Yes Yeses, and to agree that we sure were suckered into fighting against each other." [4]

Nonetheless, community divisions over differing responses to the incarceration continue to linger. As filmmaker Chizu Omori—whose film Rabbit in the Moon explores these divisions—notes, "The tragedy is that for many, the lines that were drawn long ago have become so hardened that dialogue seems almost impossible." [5]

For More Information

Murray, Alice Yang. Historical Memories of the Japanese American Internment and the Struggle for Redress . Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008.

Okada, John. No-No Boy . Rutland, VT: Charles E. Tuttle, 1957. San Francisco: Combined Asian American Resources Project, Inc., 1976. Introd. Lawson Fusao Inada. Afterword by Frank Chin. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1979.

Omori, Chizu. "The Life and Times of Rabbit in the Moon ." In Last Witnesses: Reflections on the Wartime Internment of Japanese Americans , edited by Erica Harth. New York: Palgrave, 2001.

PBS. Rabbit in the Moon . Last modified Feb. 11, 2011. https://www.pbs.org/pov/films/rabbitinthemoon/

Footnotes

- ↑ Of the 77,842 "eligible to register," 65,312 answered yes to question 28, 3,254 refused to register, 2,083 gave a qualified answer, 6,733 answered "no," 426 did not answer, and 34 were "unknown." The Evacuated People: A Quantitative Description , United States Department of the Interior, n.d. [1946], 164, Table 73.

- ↑ For examples of this in the vernacular press, see the Hawaii Herald , September 1, 1989, 16 ("Simply put, the 'No-No Boys' were those men sent from internment camps to prison for refusing the U.S. Army draft.") and November 17, 2000, A-15 ("Darrell Kunitomi, who plays a Japanese American refusing to fight for the United States in the war, was approached by a 442nd RCT veteran who revealed that the show taught him the 'no-no boy' perspective.")

- ↑ Gary Tachiyama and Roland Kotani, "No-no Boys: Old and New," The Hawaii Herald , July 3, 1981, 1.

- ↑ Comments by Ben Takeshita at the Tule Lake plaque dedication July, 1977, cited in Alice Yang Murray, Historical Memories of the Japanese American Internment and the Struggle for Redress (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008), 278.

- ↑ Chizu Omori, "The Life and Times of Rabbit in the Moon " in Last Witnesses: Reflections on the Wartime Internment of Japanese Americans , ed. Erica Harth (New York: Palgrave, 2001), 227–28.

Last updated Feb. 20, 2024, 5:41 a.m..

Media

Media