Redress movement

The Redress Movement refers to efforts to obtain the restitution of civil rights, an apology, and/or monetary compensation from the U.S. government during the six decades that followed the World War II mass removal and confinement of Japanese Americans. Early campaigns emphasized the violation of constitutional rights, lost property, and the repeal of anti-Japanese legislation. 1960s activists linked the wartime detention camps to contemporary racist and colonial policies. In the late 1970s three organizations pursued redress in court and in Congress, culminating in the passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 , providing a national apology and individual payments of $20,000 to surviving detainees.

Early Efforts

During the war, Japanese Americans protested mass incarceration without due process in a variety of ways. Minoru Yasui , Gordon Hirabayashi , and Fred Korematsu , and other Japanese Americans challenged the constitutionality of the curfew, exclusion and confinement policies. [1] Some detainees refused to sign a loyalty questionnaire while behind barbed wire and others participated in strikes and demonstrations. [2] After the draft was reinstated in 1944, several groups, including the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee , encouraged detainees to defy induction procedures until the government clarified detainees' "citizenship status" and constitutional rights. [3] When the War Relocation Authority announced plans to close the camps in 1945, thirty representatives from seven camps attended an All-Center Conference in Salt Lake City and sent a protest letter demanding the government provide financial redress before forcing detainees out of the camps. [4]

Leaders of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) advocated military service to demonstrate loyalty and improve the treatment of detainees. [5] Camp administrators and government officials rewarded JACL's emphasis on loyalty, military valor, and cooperation by supporting the 1948 Evacuation Claims Act . Providing token compensation for lost property, this act excluded lost opportunities, earnings, or interest. [6] While 23,689 Japanese Americans applied for a total of $131,949,176 in damages, Congress appropriated $38 million for all claims. The Justice Department required written receipts that many detainees lost when uprooted from their homes. To avoid these bureaucratic procedures, many claimants accepted a government offer to provide $2,500 or three-fourths of their claim, whichever was less. [7] JACL also successfully lobbied for the 1952 McCarran-Walter Act giving Issei (first generation immigrants) the right to become naturalized citizens, and the repeal of alien land laws denying Issei the right to own land. [8]

Social Movements and Redress Campaigns

Civil rights, antiwar, and ethnic pride movements in the 1960s and 1970s resurrected and intensified Japanese American criticism of the mass detention. In 1967, Raymond Okamura and Edison Uno organized a JACL grassroots crusade to repeal Title II of the Internal Security Act of 1950 authorizing mass detention of suspected subversives without trial. Demonstrations of widespread community support convinced JACL leader Mike Masaoka and Japanese American politicians Spark Matsunaga and Daniel Inouye to support the movement that culminated in the repeal of Title II in 1971. [9] This combination of community activism followed by political lobbying also led to the official rescission of Executive Order 9066 in 1976 and the pardoning of Iva Toguri (convicted of treason as "Tokyo Rose") in 1977. [10]

In 1970 the JACL endorsed Edison Uno's resolution exhorting Congress to "compensate on an individual basis a daily per diem requital for each day spent in confinement and/or legal exclusion" but committed no resources. [11] National leaders Mike Masaoka and Bill Hosokawa argued that calling for monetary compensation would cheapen the sacrifice of Japanese American veterans and revive anti-Japan racism. [12] Refuting government claims of "military necessity," the 1976 book Years of Infamy by former detainee Michi Weglyn , inspired more protests against American "concentration camps" and JACL leaders' depictions of wartime patriotism and postwar recovery. [13] Clifford Uyeda , leader of the Toguri pardon campaign, became JACL president in 1978 and appointed John Tateishi, another JACL outsider, as chair of a newly formed Redress Committee. In 1979 Japanese American politicians convinced Tateishi's Redress Committee to switch from pursuing monetary compensation to lobbying for the creation of a federal commission to investigate the causes and consequences of the mass exclusion and incarceration.

The Commission on the Wartime Internment and Relocation of Civilians (CWRIC)

Congress and President Jimmy Carter approved the creation of a Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) in 1980. This bipartisan commission held 20 days of hearings with more than 750 witnesses and spent a year and a half researching scholarship and archival sources. [14] Ironically while JACL's advocacy of a commission proposal was criticized as a ploy to avoid monetary redress, the actual 1981 hearings expanded and strengthened community support for redress. [15] More than 500 former detainees testified, and many had never shared their experiences with the public or even their own children. Their accounts of pain and suffering galvanized redress support from Japanese Americans who attended the hearings or read excerpts of testimony in newspapers and magazines. JACL leaders and members testified at every hearing location and consistently urged the Commission to recommend that Congress provide an apology and compensation of $25,000 to each person who suffered exclusion and detention. [16]

The Commission's 1983 report acknowledged the injustice of mass exclusion, removal and detention and concluded these policies were caused not by "military necessity" but by "race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership." [17] Four months later, the Commission recommended Congress and the President issue a national apology, establish a foundation to educate the public, and provide $20,000 to each surviving detainee. [18] Commission chair Joan Bernstein later explained that the $20,000 amount was selected to avoid the appearance that the Commission was "in the JACL's pocket" while still providing a figure close to the $25,000 figure requested most often by JACL leaders and former detainees. [19] Limiting redress eligibility to living victims helped alleviate concern redress could set a precedent for the descendants of slaves, American Indians forced onto reservations, Mexicans who lost land, and other historical victims of racism. [20]

Different Philosophies Toward Redress: the National Council for Japanese American Redress Class Action Lawsuit and the Grassroots Lobbying of the National Coalition for Redress/Reparations

Critics of JACL support for a commission proposal in 1979 created two separate organizations. JACL dissidents in Seattle and Chicago formed the National Council for Japanese American Redress (NCJAR) and supported Washington Congressman Michael Lowry 's bill that year that called for reparations payments to former detainees of $15,000 plus $15 per day of incarceration. [21] After Lowry's bill died in committee, NCJAR, led by William Hohri , continued criticizing JACL "collaboration," celebrated wartime resisters , and filed a class action lawsuit in 1983. Providing 22 causes of action, the lawsuit demanded $220,000 per victim for "constitutional violations, loss of property and earnings, personal injury, and pain and suffering." [22] NCJAR charges of government fraud and conspiracy were bolstered when Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga , an NCJAR supporter and CWRIC researcher, uncovered evidence the government deliberately withheld from the Supreme Court a draft report by Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt declaring Japanese American loyalty could never be determined because "it was impossible to separate the sheep from the goats." [23] Legal historian Peter Irons and a team of Sansei (third generation) lawyers used this document and other evidence concealed from the Supreme Court to successfully petition for a writ of coram nobis (meaning "the error before us") vacating the wartime convictions of Minoru Yasui, Gordon Hirabayashi, and Fred Korematsu. [24] The Supreme Court heard NCJAR arguments in 1986, decided the lawsuit belonged in another jurisdiction, and ordered that the case be heard by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. NCJAR's campaign for judicial redress ended in 1988 when the Supreme Court declined to re-consider the Appeals Court's dismissal of the suit. [25]

The National Coalition for Redress/Reparations (NCRR), led primarily by Sansei activists, also challenged JACL redress leadership. NCRR founders included Manzanar Committee members who organized yearly pilgrimages to the Manzanar camp and conducted a community survey indicating overwhelming support for both an apology and monetary redress. Many NCRR activists had denounced American imperialism in Vietnam, protested against redevelopment in urban areas as a second "forced relocation," and supported multiethnic and multiracial campaigns against racism. [26] Afraid the JACL might limit participation in the Commission hearings to JACL leaders, veterans, politicians, and scholars, NCRR distributed leaflets and held workshops encouraging working-class and non-English speaking detainees to testify. NCRR letters, telegrams, phone calls, and petitions led to the addition of a Los Angeles community hearing in the evening and Japanese translators at the Los Angeles and San Francisco hearings. [27] In 1987 120 NCRR activists made 101 visits to congressional offices in Washington, D.C. [28] Veteran Rudy Tokiwa persuaded conservative Congressman Charles Bennett to support redress by recounting how only 17 of 258 members in his company survived the Battle of the Lost Battalion in the Vosges mountains. [29] NCRR activists sent more than 20,000 letters endorsing redress compensation. [30] Congressman Robert Matsui praised NCRR's role in "keeping the community informed and building local support" while Congressman Norman Mineta celebrated how NCRR's "grass roots action and advocacy have energized" Japanese Americans. [31]

The Passage of Redress Legislation

After the Commission issued its recommendations in 1983, the JACL immediately launched a campaign urging Japanese American members of Congress to implement the Commission's call for an apology and individual compensation. Proposed bills in the House and the Senate never made it out of committee until 1987 when Massachusetts Congressman Barney Frank chaired the House Subcommittee on Administrative Law and Ohio Senator John Glenn chaired the Senate Governmental Affairs Committee. [32] Coordinating JACL outreach efforts, Grayce Uyehara distributed sample form letters, lobbying advice, and "action alerts" scoring the position on redress of every member of Congress. By 1987 more than 200 organizations, including veterans groups and state legislatures, endorsed monetary redress. Congressmen Norman Mineta and Robert Matsui spoke eloquently about their incarceration as children and the suffering of their families when they urged the full House to approve redress legislation named H.R. 442 to honor the Japanese American 442nd Regimental Combat Team , the most decorated unit for its size and length of service. Mineta and House Speaker Jim Wright arranged to have the legislation discussed on September 17, 1987, the bicentennial of the Constitution. Spark Matsunaga, a decorated veteran from Hawai'i and a popular senator, rounded up 75 co-sponsors in the Senate. [33] JACL lobbyist Grant Ujifusa appealed to conservative supporters by presenting redress as a tribute to patriotism and military heroism, a reward for a "model minority," and an attack on Franklin Delano Roosevelt's big government. Ujifusa also persuaded Republican Governor Thomas Kean to convince President Ronald Reagan to sign the redress bill. Kean reminded Reagan of a speech he gave as an army captain at a December 1945 ceremony presenting the family of Kazuo Masuda with a posthumous Distinguished Service Cross. Quoting from this speech, Reagan declared, "blood that has soaked into the sands of a beach is all of one color," at a ceremony where he signed the Civil Liberties Act on August 10, 1988. [34]

Redress Appropriations

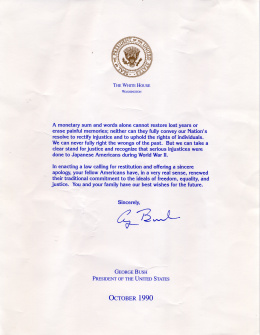

Senator Daniel Inouye became an important leader during the struggle for redress appropriations and succeeded in making redress an entitlement. In a 1990 ceremony in Washington D.C. Attorney General Richard Thornburgh presented the nine oldest surviving detainees a written apology signed by George H.W. Bush and a check for $20,000. [35] The Commission miscalculated when it estimated that there were approximately 60,000 surviving internees using actuarial tables based on white male life expectancies. Ultimately the Office of Redress Administration (ORA) identified, located, and paid $20,000 to 82,250 former detainees for a total of more than $1.6 billion before it officially closed in February 1999. [36]

Most Japanese Latin American internees, however, had to fight to receive any redress compensation because they were initially excluded from the provisions of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which limited redress to U.S. citizens and permanent residents. Understandably Japanese Latin Americans were outraged that after being uprooted from their homes and shipped to U.S. internment camps, they were denied redress because they had been labeled by the Immigration and Naturalization Service as "illegal aliens." [37] In 1996 Japanese Latin Americans filed a class action lawsuit, Carmen Mochizuki et. al. v the United States , to obtain redress. NCRR, JACL, the Japanese Peruvian Oral History Project, and the Southern California chapter of the ACLU joined the coalition Campaign for Justice: Redress Now for Japanese Latin Americans and negotiated a 1998 settlement providing an apology and individual payments of $5,000. [38] The ORA, however, ran out of funds after paying only 145 claimants and denied redress to more than 500 other eligible recipients. The Coalition sued the government for "breach of fiduciary duty" before Congress authorized an additional $4.3 million. [39] As of 2012, activists continue lobbying the U.S. government to provide Japanese Latin Americans with redress equity and the same $20,000 compensation amount given to Japanese Americans [40]

Redress Lessons

The Campaign for Justice illustrates how JACL and NCRR leaders have united to support other redress efforts. In the late 1970s JACL, NCRR, and NCJAR leaders may have developed separate organizations and promoted different strategies but all three strengthened the redress movement. Mobilizing diverse constituencies inside and outside the Japanese American community, the three campaigns became, in the words of Gordon Nakagawa, "three strands woven into a single fabric." [41] JACL won support for the creation of a federal commission that acknowledged the injustice of mass detention and recommended compensatory redress. JACL lobbyists gained support from conservatives as well as liberals and persuaded Reagan not to veto the legislation. NCRR enlisted the participation of ordinary Japanese Americans in the hearings and in congressional lobbying campaigns and displayed widespread community support for redress. NCJAR research and publicity documented constitutional violations and provided evidence used by other redress groups. NCJAR's calls for $220,000 for each wartime victim also made legislative demands for $20,000 per internee seem moderate. [42]

When Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, he proclaimed the government affirmed that day "our commitment as a nation to equal justice under the law." [43] Some Japanese American activists might agree and characterize the redress movement as a shining example of the greatness of American democracy. Other activists, however, believe the real lesson of redress is the need for continued vigilance to make sure civil liberties are never again sacrificed because of war hysteria or racism. After 9/11, these activists participated in demonstrations denouncing hate crimes, racial profiling, and unconstitutional detentions. Remembering how few Americans protested the decision to remove and incarcerate Japanese Americans in 1942, these individuals and groups wanted to prevent history from repeating itself and victimizing Arab, Muslim, and South Asian Americans because of wartime racism. These activists continue to call for the protection of the rights of immigrants and citizens targeted for government round-ups and deportation during the "War on Terror." They also continue to criticize the denial of due process, by the George W. Bush administration and by the Barack Obama administration, for "suspected terrorists" and "enemy combatants." [44]

For More Information

Print Resources

Scott, Esther, and Calvin Naito. "Against All Odds: The Japanese Americans' Campaign for Redress." Cambridge, MA: Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, 1990.

Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians . Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1982.

Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. Personal Justice Denied, Part II: Recommendations . Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1983.

Maki, Mitchell T., Harry H. L. Kitano, and S. Megan Berthold. Achieving the Impossible Dream: How Japanese Americans Obtained Redress . Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1999.

Hatamiya, Leslie T. Righting a Wrong: Japanese Americans and the Passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 . Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1993.

Hohri, William. Repairing America: An Account of the Movement for Japanese-American Redress . Pullman: Washington State University Press, 1984.

Murray, Alice Yang. Historical Memories of the Japanese American Internment and the Struggle for Redress . Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007.

Yamamoto, Eric K., et al. Race, Rights and Reparation: Law and the Japanese American Internment . Gaithersburg, NY: Aspen Publishers, 2001.

Films

The Color of Honor . Loni Ding. Asian American Telecommunications Association, 1996. VHS.

Conscience and the Constitution . Frank Abe. Transit Media, 2000. VHS.

Of Civil Wrongs & Rights: the Fred Korematsu Story . Eric Paul Fournier. National Asian American Telecommunications Association, 2000. VHS.

A Personal Matter: Gordon Hirabayashi versus the United States . John DeGraaf. National Asian American Telecommunications Association, 1992. VHS.

Rabbit in the Moon . Emiko Omori. Furumoto Foundation, 2004. DVD.

Redress: The JACL Campaign for Justice . Cherry Kinoshita. Visual Communications, 1991. VHS.

Resettlement to Redress: Re-Birth of the Japanese American Community . Don Young. PBS, 2005. DVD.

Uncommon Courage: Patriotism and Civil Liberties . gayle k. yamada. Bridge Media, 2001.VHS.

Unfinished Business: the Japanese-American Internment Cases . Steven Okazaki. New Video, 2005. DVD.

Online Resources

Campaign for Justice. Accessed August 20, 2012. http://www.campaignforjusticejla.org .

Conscience and the Constitution. Accessed August 20, 2012. http://www.resisters.com .

Japanese American Citizens League. "Historical Overview." Accessed August 20, 2012. https://jacl.org/history

Japanese American National Museum. "Redress Movement Selected Bibliography." Accessed August 20, 2012.

http://media.janm.org//events/2008/redress/redress_bibliography.pdf

.

Japanese American Voice. Accessed August 20, 2012. https://manzanarcommittee.org/who-we-are/

Manzanar Committee. Accessed August 20, 2012. http://blog.manzanarcommittee.org/about-the-manzanar-committeecontact-us/ .

National Japanese American Memorial Foundation. Accessed August 20, 2012. http://njamf.com .

Nikkei for Civil Rights & Redress. Accessed August 20, 2012. http://www.ncrr-la.org .

Footnotes

- ↑ Peter Irons, Justice at War: The Story of the Japanese American Internment Cases (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983) and Justice Delayed: The Record of the Japanese American Internment Cases , ed. Peter Irons (Middleton, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1989).

- ↑ Dorothy Swaine Thomas and Richard S. Nishimoto, The Spoilage: Japanese-American Evacuation and Resettlement during World War II (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1946); Donald E. Collins, Native American Aliens: Disloyalty and Renunciation of Citizenship by Japanese Americans during World War II (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985).

- ↑ Kiyoshi Okamoto, Fair Play Committee memo, Heart Mountain, March 26, 1944, courtesy of George Nozawa. The draft was reinstated for Japanese Americans in 1944. Sixty-three Heart Mountain resisters were prosecuted in a single trial, convicted of draft evasion, sentenced to three years in prison, and then pardoned by Harry Truman in 1947. See Douglas W., Heart Mountain: The History of an American Concentration Camp (Madison: The State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1976). For other examples of draft resistance, see Eric Muller, Free to Die for Their Country: The Story of the Japanese American Draft Resisters in World War II (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001) and Cherstin Lyon, Prisons and Patriots: Japanese American Wartime Citizenship, Civil Disobedience, and Historical Memory (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2012).

- ↑ WRA, Community Government in War Relocation Center (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, [1946]), 99.

- ↑ Bill Hosokawa, JACL: In Quest of Justice; History of the Japanese American Citizens League (New York: William Morrow, 1982), 275. During the war, the JACL dwindled to only 1,700 members but was recognized by the government as representing the entire community.

- ↑ See Nancy Nanami Nakasone-Huey, "In Simple Justice: The Japanese-American Evacuation Claims Act of 1948," Ph.D. diss., University of Southern California, 1986, 346.

- ↑ According to the WRA, 76,843 adult individuals were eligible to file claims. See War Relocation Authority, The Evacuated People: A Quantitative Description (Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1946), 96-97. Sixty percent of these claims were for less than $2,500. A ninety-two-year-old accepted $2,500 for a $75,000 claim because he didn't think he would live long enough to see his claim through the courts. Others pursued litigation, but the last claim was not settled until 1965. See Bill Hosokawa, Nisei: The Quiet Americans; The Story of a People (New York: William Morrow, 1969), 446.

- ↑ Mike Masaoka recounts his lobbying efforts on behalf of Issei naturalization rights in They Call Me Moses Masaoka: An American Saga (New York: William Morrow, 1987), 221-222. For campaigns against alien land laws, see Kevin Allen Leonard, "'Is That What We Fought For?' Japanese Americans and Racism in California: The Impact of World War II," Western Historical Quarterly 21, no. 4 (November 1990): 469-475.

- ↑ See Raymond Okamura, Robert Takasugi, Hiroshi Kanno, and Edison Uno. "Campaign to Repeal the Emergency Detention Act," Amerasia Journal 2, no. 2 (Fall 1974), 72-111.

- ↑ For the rescission of Executive Order 9066 and early redress activism, see Robert Sadamu Shimabukuro, Born in Seattle: The Campaign for Japanese American Redress (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003); Yasuko Takezawa, Breaking the Silence: Redress and Japanese American Ethnicity (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1995); and Bill Hosokowa, JACL: In Quest of Justice , 339-41. For the Toguri pardon, see Clifford I. Uyeda, A Final Report and Review: The Japanese American Citizens League National Committee for Iva Toguri (Seattle: Asian American Studies Program, University of Washington, 1980). For more analysis of the dynamic between Japanese American radical grassroots campaigns and political lobbying by JACL leaders with conservative credentials, see Alice Yang Murray, Historical Memories of the Japanese American Internment and the Struggle for Redress (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007).

- ↑ Edison Uno, "A Requital Supplication," Edison Uno Collection, Special Collections, University Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles, Box 38, Folder 3.

- ↑ Bill Hosokawa, "Out of the Frying Pan," Pacific Citizen , November 7, 1956 and Mike Masaoka, "JACL in the 1970s," Pacific Citizen , January 2-9, 1970.

- ↑ A small number of former detainees participated in desegregation and antinuclear campaigns in the 1950s but many more joined Sansei (3rd generation) activists in the civil rights, antiwar, and ethnic pride movements of the 1960s and 1970s and read Michi Weglyn's Years of Infamy: the Untold Story of America's Concentration Camps (New York: William Morrow, 1976). See Raymond Okamura, "The Concentration Camp Experience from a Japanese American Perspective: A Bibliographic Essay and Review of Michi Weglyn's Years of Infamy," in Counterpoint: Perspectives of Asian America , ed. Emma Gee (Los Angeles: University of California Asian American Studies Center, 1976), 27-30. JACL redress leader Clifford Uyeda and NCJAR leader William Hohri paid tribute to Weglyn for debunking the myth of "military necessity," documenting government racism, and recounting the suffering of Japanese American detainees. See Clifford Uyeda, "Letters from our Readers, " Pacific Citizen , July 16, 1976 and William Hohri, "Dear Friends," National Council for Japanese-American Redress (NCJAR) Newsletter , November 5, 1982, 1.

- ↑ President Carter, the House of Representatives, and the Senate each appointed three members to the Commission. Carter chose Dr. Arthur S. Flemming , chairman of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights and former Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare under President Eisenhower; Joan Bernstein , former general counsel of the Department of Health and Human Services; and former internee Judge William Marutani of the Philadelphia court of common pleas. The House selected former Supreme Court justice Arthur J. Goldberg , Republican Congressman Daniel Lungren of Long Beach, and Father Robert F. Drinan , a Jesuit priest and congressman from Massachusetts. The Senate named Edward W. Brooke , a black Republican and former Massachusetts senator; Hugh B. Mitchell , a former Democratic senator from Seattle; and Father Ishmail Vincent Gromoff , a Russian Orthodox priest.

- ↑ For criticism of the JACL, see Frank Abe and Karen Seriguchi, "Critique of Commission Approach," Rikka 6, no. 3 (Autumn 1979), 40 and Shosuke Sasaki , "Concerning Governmental Redress for Evacuation," Hokubei Mainichi , January 29, 1980.

- ↑ In 1978 JACL's Redress Committee called for compensation regardless of an individual's age or national origin; to give these funds to the heirs of detainees who had passed on; and to establish a 100 million dollar trust administered by a commission of Japanese Americans selected from the community. Ironically, the committee based the $25,000 figure on Mike Masaoka's claim that the Federal Reserve determined Japanese Americans had lost $400 million worth of property during the mass incarceration. Masaoka later confessed to Tateishi that he had simply invented this figure during government hearings for the 1948 Evacuation Claims Act. Author's interview of John Tateishi (March 16, 1998).

- ↑ The Commission on the Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, Personal Justice Denied: The Report of the Commission on the Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1982): 283-293.

- ↑ The Commission on the Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, Personal Justice Denied, Part Two: Recommendations (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1983), 8-10.

- ↑ Author's interview of Joan Bernstein (March 26, 1998).

- ↑ Author's interview of William Marutani (May 19, 1998).

- ↑ For the Lowry bill, see the Congressional Record , 96th Congress, First Session 125, No. 167, November 28, 1979 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1979).

- ↑ Testimony of William Hohri, Record Group 220, Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians ,Washington, DC, July 16, 1981, CWRIC files, National Archives. Twenty-five Japanese Americans agreed to appear as plaintiffs and NCJAR raised more than $300,000 and publicized their activities in monthly newsletters to 1,500 subscribers. See William Hohri, Repairing America: An Account of the Movement for Japanese-American Redress (Pullman: Washington State University Press, 1984), 225.

- ↑ NCJAR maintained that the failure of more than 40 lawsuits filed during and after the war served as evidence of the government's "conspiracy, misrepresentations, fraud, and concealment of evidence." See "Plaintiff's Supplemental Memorandum on the Statute of Limitations," January 20, 1984, Hohri et al. v. United States and Appeal No. 84-5460, Hohri et al., v. The United States , United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, October 12, 1984.

- ↑ See Korematsu v. United States , 584 F. Supp. 1406 (N.D. California 1984) and Dale Minami, "Coram Nobis and Redress," Japanese Americans: From Relocation to Redress , edited by Roger Daniels, Sandra C. Taylor, and Harry H. L. Kitano (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1986), 201.

- ↑ Hohri, Repairing America , 223.

- ↑ For information on the Manzanar Committee, see http://www.manzanarcommittee.org/The_Manzanar_Committee/About_Us.htmlWorking for Redress. Many NCRR leaders had been active in the Committee Against Nihonmachi Evictions in the Bay Area or in the Little Tokyo People's Rights Organization in the Los Angeles area. Both groups fought "urban renewal" plans that would evict poor and elderly former detainees, promoted Marxist revolutionary ideology, and denounced multinational corporations. See Glen Ikuo Kitayama, "Japanese Americans and the Movement for Redress: A Case Study of Grassroots Activism in the Los Angeles Chapter for the National Coalition for Redress/Reparations," Master's thesis, University of California, Los Angeles, 1993.

- ↑ National Coalition for Redress and Reparations (NCRR) Steering Committee Meeting, December 5, 1981; NCRR Flyer, n.d., courtesy of Jim Matsuoka. See also the author's interview of Alan Nishio (Los Angeles, CA, July 10, 1993) and the author's interview of Bert and Lillian Nakano (Gardena, CA, July 8, 1993).

- ↑ National Coalition for Redress and Reparations (NCRR) Steering Committee Meeting, December 5, 1981; NCRR Flyer, n.d., courtesy of Jim Matsuoka. NCRR grew from 1,000 members during the hearings to 8,000 who supported lobbying delegations sent to Capitol Hill in 1984 and 1987.

- ↑ NCRR Banner , August, 1987, 1.

- ↑ Author's interview of Sox Kitashima, August 13, 1990.

- ↑ National Coalition for Redress and Reparations brochure (N.p., n.d.), courtesy of Jim Matsuoka.

- ↑ In 1983, HR 4110 called for individual payments of $20,000 to an estimated 60,000 survivors for a total cost of $1.5 billion. Frank made redress a priority and focused on comparing different implementation methods. See Hearings before the Subcommittee on Administrative Law and Governmental Relation of the Committee on the Judiciary , House of Representatives, Ninety-Ninth Congress, Second Session, HR 442 and HR 2415 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1987). For more on JACL political lobbying, see Calvin Naito and Esther Scott, "Against All Odds: The Japanese Americans' Campaign for Redress," (Cambridge, MA: Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, 1990),15. See also Leslie Hatamiya, Righting a Wrong: Japanese Americans and the Passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1993), 101-102 and 108 and Grant Ujifusa, "The Same Car to Both Guys," Pacific Citizen , January 2, 1998.

- ↑ George Johnson, "Ujifusa Reveals 'Behind the Scenes' Look Behind Redress Success," Pacific Citizen , August 19-26, 1988.

- ↑ Naito and Scott, 27 and Ujifusa, "The Same Car to Both Guys."

- ↑ Ronald J. Ostrow, "First Nine Japanese World War II Internees Get Reparations," Los Angeles Times , October 10, 1990, A1.

- ↑ U.S. Department of Justice, "Ten Year Program to Compensate Japanese Americans Interned During World War II Closes Its Doors," (February 19, 1999), http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/1999/February/059cr.htm , Retrieved on August 20, 2012.

- ↑ During the war 2,264 Japanese Latin Americans were kidnapped from their homes in Central and South America, shipped to US internment camps for prisoner exchanges with the Japanese, and declared "illegal aliens" by the US government subject to deportation to Japan at the end of the war. See Weglyn, Years of Infamy ; and C. Harvey Gardiner, Pawns in a Triangle of Hate: The Peruvian Japanese and the United States (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1981).

- ↑ Campaign for Justice Forms a Northern California Chapter," Nichi Bei Times , March 28, 2000.

- ↑ Jason Ma, "Reparations Suit Dismissed," Asian Week , November 25, 1999.

- ↑ In 2000 Congressman Xavier Becerra from Los Angeles, introduced legislation providing Japanese Latin Americans $20,000 in compensation. The bill failed and in 2006 Congressman Becerra and Senator Daniel Inouye began lobbying for the creation of a federal commission. Other activists accused the US government of "war crimes and crimes against humanity" in a petition to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, a subset of the Organization of American States. For more information, see Editorial, Japanese Latin American internees deserve full redress," Honolulu Star-Bulletin , October 7, 2006 and www.campaignforjusticejla.org/history, accessed on August 20, 2012.

- ↑ Gordon Nakagawa, "Redress: More Work in the Midst of Victories," NCRR Banner , May 1986.

- ↑ Mitchell T. Maki et al., Achieving the Impossible Dream: How Japanese Americans Obtained Redress (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1999), 128.

- ↑ Ronald Reagan, speech at the August 10, 1988 signing of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, quoted at http://njamf.com .

- ↑ Japanese American individuals and groups continue to work with Arab, Muslim, and South Asian Americans to challenge discriminatory government policies. The JACL's "Bridging Communities" program promotes dialogue, understanding, and partnerships between Japanese Americans, American Muslim and Arab American civil liberties groups. See http://www.jacl.org/youth/youth.htm . NCRR became the The Nikkei for Civil Rights and Redress and established an NCRR 9/11 Committee that held a series of educational programs with the Revolutionary Alliance of Women from Afghanistan, the Muslim Public Affairs Council, the Council on American-Islamic Relations, and the American Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee. See Nikkei for Civil Rights and Redress 9/11 Committee, http://www.ncrr-la.org/about.html . Organizers of a 2003 Day of Remembrance program in Sacramento featured the panel "How Can We Defend Our Constitution?: From Japanese American Internment in 1942 to Backlash Against Arab, Muslim, and Sikh Americans Today" so that leaders from the different communities could share ideas on what we can all do to "stand up for our neighbors." See "Sacramento Time of Remembrance Program," Nichi Bei Times , February 22, 2003.

Last updated Jan. 30, 2024, 1:27 a.m..

Media

Media