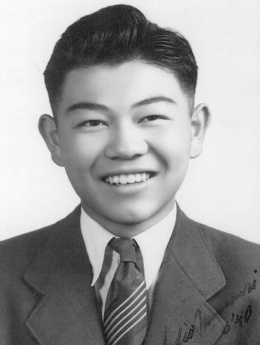

Sadao Munemori

| Name | Sadao Munemori |

|---|---|

| Born | August 17 1922 |

| Died | 1945 |

| Birth Location | Glendale, CA |

| Generational Identifier |

Nisei war hero, Congressional Medal of Honor recipient. For over five decades, Sadao Munemori (1922–45), a Nisei from Los Angeles, was the only Japanese American to be awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, the country's highest military award, for his service in World War II.

Soldier

Sadao Munemori was born on August 17, 1922, to Kametaro and Nawa Munemori, immigrants from Hiroshima prefecture, in Glendale, California, a suburb of Los Angeles, the fourth of five children. He attended Fletcher Drive Elementary School and Lincoln High School, graduating in 1940. After his graduation, he entered Frank Wiggins Trade School, studying to become an auto mechanic. Unable to get a job as a mechanic after graduating, he decided to enlist in the army in February 1942. [1]

Like many of the Nisei already in the army prior to the formation of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team , Munemori entered a sort of limbo, barred from combat training and relegated to menial jobs at Camp Robinson in Arkansas and Camp Grant in Illinois. (See Japanese Americans in military during World War II .) William Shinji Tsuchida, a friend who knew Munemori and who was in the same situation later recalled,

In 1942, the Army on the mainland was at a loss as to what to do with us 18 and 19 year old Asians with no college degrees. So most of us were shipped to army bases located in the Midwest, away from the west or east coast.... We were assigned all the menial jobs, where we had to endure—permanent KP, peeling mountains of potatoes daily, cleaning bed pans at the base hospital. Not my idea of patriotic duty. [2]

He also did a stint at Camp Savage, preparing that camp for the Military Intelligence Service Language School . Along the way, he picked up the nickname "Spud," reportedly because he was the rare Nisei who preferred potatoes to rice. In the meantime, his family was forcibly removed along with all other West Coast Japanese Americans, ending up confined at the Manzanar camp in central California.

After the formation of the 442nd early in 1943, earlier inductees such as Munemori were once again allowed bear arms and most were assigned spots in the 442nd. Munemori went to Camp Shelby in January 1944 and became a 100th Infantry Battalion replacement. He went overseas in April of 1944, seeing action in Italy, then in France, where he took part in the rescue of the Lost Battalion .

In 1945, he returned with the 442nd to Italy. In the assault on the Gothic Line on the morning of April 5, he found himself in charge of his squad when his squad leader fell wounded. Trapped with two others in a shell crater by machine gun fire with grenades being hurled at them, Munemori crawled out of the crater and knocked out the enemy machine gun nests with grenades. Scrambling back to the crater, a grenade bounced off his helmet and into the crater. He smothered it with his body and was killed instantly. The other two men suffered concussions and partial deafness but survived.

Honors and Legacy

For his heroic actions, Munemori was posthumously awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, the only one awarded to a Nisei in the immediate aftermath of the war. (A review in the 1990s led to the awarding of twenty additional medals to Japanese American soldiers for their actions in World War II.) The medal was presented to his mother on March 13, 1946.

In 1948, the 10,000 ton troop ship "Wilson Victory" was renamed the "Pvt. Sadao S. Munemori." In addition, the interchange of the 105 and 405 freeways in Los Angeles is named the "Sadao S. Munemori Memorial Interchange, Medal of Honor—World War II" and in 1993, the "Sadao S. Munemori Hall" at the U.S. Army Reserve Complex in West Los Angeles was dedicated. Most recently the town of Pietrasanta, Italy dedicated a statue of Munemori by sculptor Marcello Tommasi on April 25, 2000.

For More Information

"An American Hero: The Story of Sadao Munemori." Nisei Vue , Summer 1949, 12–14.

Aoyagi-Storm, Caroline. "A Hometown Honor for Sadao Munemori?" Pacific Citizen , April 18, 2008.

Crost, Lyn. Honor by Fire: Japanese Americans at War in Europe and the Pacific . Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1994.

Mori, Henry. "Sadao Munemori: Nisei of '46." Rafu Shimpo , Holiday Issue, Dec. 1946, 7–8.

Tamashiro, Ben. "The Congressional Medal of Honor: Sadao Munemori." Hawaii Herald 6.6 (March 15, 1985): 10–11.

Tsuchida, William. " Peek Into the Past: My Friend, Spud. " Puka Puka Parade , Oct. 2007.

Footnotes

- ↑ There is conflicting information with various sources on when he enlisted, with some suggesting he enlisted just prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor, some saying he enlisted after the attack, and others saying that he volunteered/was recruited from Manzanar to attend the Military Intelligence Service Language School. His enlistment record in the National Archives ( http://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=893&mtch=1&tf=F&q=sadao+munemori&bc=&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=7559539 ) indicates that he was inducted on February 11, 1942. This date is confirmed by a 1946 interview with his brother Isao and mother Nawa by journalist Henry Mori ("Sadao Munemori: Nisei of '46," Rafu Shimpo , Holiday Issue, Dec. 1946, 7–8). Accounts by Sue Kunitomi [Embrey] in the Pacific Citizen (April 6, 1946, http://ddr.densho.org/ddr-pc-18-14/ ) and Ben Tamashiro's account in the Hawaii Herald (Marcy 15, 1985, http://nisei.hawaii.edu/object/io_1149130450078.html ) both cite a November 1941 enlistment date. A check of the family records in the "Japanese-American Internee Data File" National Archives database ( http://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=893&mtch=1&tf=F&q=sadao+munemori&bc=&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=7559539 ) shows his mother and three siblings at Manzanar (the fourth was in Japan) but not Sadao.

- ↑ William Shinji Tsuchida, "Peek Into the Past: My Friend, Spud," Puka Puka Parade , Oct. 2007, accessed on May 4, 2012, http://www.100thbattalion.org/archives/puka-puka-parades/mainland-training/discrimination/peek-into-the-past-my-friend-sadao-spud-munemori/ .

Last updated April 11, 2024, 5:22 p.m..

Media

Media