Terrorist incidents against West Coast returnees

In the first year after Japanese Americans were allowed to return to the West Coast, they were greeted by dozens of terrorist incidents that included gunshots fired into homes, arson fires, threats, and vandalism. These incidents took place mostly in rural areas of Central California and, in combination with vocal efforts to dissuade Nikkei from returning to West Coast communities, were an attempt to intimidate those who wanted to return. Thanks in part to the reaction of state and federal officials, vigorous law enforcement, and national publicity, the attacks largely stopped by the end of 1945.

The West Coast was opened to "loyal" Japanese Americans in January of 1945. (See Return to West Coast .) Those who sought to return faced vigorous opposition driven by a variety of factors including reports of unrest at some of the camps as well as the supposed "coddling" of the incarcerated Nikkei, continuing reports of atrocities committed by Japanese troops in Asia, and economic interests on the coast that were benefiting from the absence of Japanese Americans.

One of the first families to return to the West Coast in January was the Doi family in Placer County, California, soon to be the epicenter of the renewed anti-Japanese agitation. Longtime residents of the area prior to the war, the Dois were confronted with a two night ordeal that involved the attempted dynamiting and burning down of their packing shed, followed by shots fired at their house from passing cars. One of the Doi sons, Shig, was at that time serving in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team in Europe, having just taken part in the rescue of the Lost Battalion . As he recounted in a later interview, "See, I was getting shot at from the enemy, and then at home in my own country, people were shooting at my dad. I was risking my life for this country, and my government was not protecting my folks. And they come home from camp with nothing." [1]

One incident after another took place in the following weeks and months: Three shotgun blasts into a Fowler home on February 10, another in Fresno on February 16, a home burned down in Selma. Shots fired into homes in Visalia and Lancaster on February 26, the Buddhist Temple in Delano burned down on February 27 followed by the Delano Japanese school going up in flames on March 11. A fire is set on a home outside of San José on March 6; when the family rushes outside to put out the fire, they are fired upon by a passing car. Five shots fired into the home of Nisei war veteran in Madera on March 26, with one of the bullets passing within five inches of his head. [2]

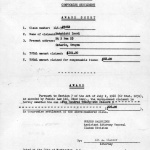

In early February, four men were arrested in the Doi case and went to trial in April. Despite the confession of one man that implicated the others, their defense attorney made no attempt to present any evidence of their innocence, instead citing the Bataan Death March and argued that "[t]his is a white man's country" while imploring the jury to keep it so. The jury acquitted the defendants of all charges. [3]

Reports of these incidents found their way back to the incarceration camps and somewhat understandably added to inmates' uneasiness about leaving the camps. As a group of the WRA social scientists in the Community Analysis Section wrote:

Fear grew in the centers. The existing hostility outside was magnified many times. People imagined what could happen to themselves if they should go back to the Coast. Even if no evacuee had yet been killed, the first to be killed might be oneself. Each new incident increased the fears, and many who had thought of going back to the Coast decided against it. [4]

As the incidents continued to pile up over the summer, several things took place. As local authorities in the central valley proved unwilling or unable to find any of the other suspects, state and federal officials stepped in, with California Attorney General Robert Kenny going so far as to send a state "special agent" to the central valley to "assist" local law enforcement in their investigations and to offer a monetary reward (put up by the American Civil Liberties Union ) for any arrest and conviction of perpetrators. In the summer, a spate of newspaper editorials from around the country decried the violence, nearly all of them citing the parallels with Nazi Germany and emphasizing the cases where the victims of the attacks were World War II veterans. Some local groups in the affected communities went out of their way to assist returning Nikkei. By June, a couple of arrests had been made in other cases, and in the fall, the Doi defendants were back on trial on federal charges. [5]

Likely the result of all of these factors—and the turn in public opinion in favor of the Japanese Americans that was beginning to take place—the attacks began to wane in the fall and slowed to a trickle by the early 1946. The vast majority of Japanese Americans returned without incident and issues of jobs and housing slowly pushed the attacks off the front pages of the vernacular newspapers.

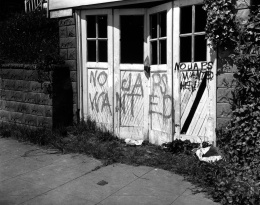

In total, there were about twenty shootings—including one into the home of a War Relocation Authority official—along with dozens of other incidents, including the defacing of Japanese graves in Fresno and the graffiti attack of famed scientist Linus Pauling's house after he hired a returning Nisei student, along with the by now commonplace arson, vandalism, and terroristic threat cases. Though most took place in the Central Valley, there were some cases in the major cities and up and down the West Coast. Miraculously, there were no deaths or serious injuries, though there were cases of the more numerous Chinese and Filipino Americans being beaten up and a Chinese American stabbed by war workers all after being mistaken for being "Japanese." There were also a couple of Nikkei who were murdered in robbery cases that didn't have obvious racial overtones. [6]

Though largely forgotten today, the terrorist incidents are an indication of the environment Nikkei returning to West Coast faced. They are also no doubt part of the reason so many Nikkei had to be forcibly evicted from the incarceration camps as they closed down throughout 1945.

For More Information

Girdner, Audrie and Anne Loftis. The Great Betrayal: The Evacuation of Japanese-Americans during World War II . New York: Macmillan, 1969.

Leonard, Kevin Allen. "'Is That What We Fought For'? Japanese Americans and Racism in California, the Impact of World War II." Western Historical Quarterly 21.4 (Nov. 1990): 463-82.

The Pacific Citizen Digital Archives. http://www.pacificcitizen.org/digital-archives .

Spicer, Edward H., Asael T. Hansen, Katharine Luomala, and Marvin K. Opler. Impounded People: Japanese Americans in the Relocation Centers . Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Interior, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1946. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1969.

Footnotes

- ↑ Pacific Citizen , January 13, 1945, 3 and January 27, 1945, 1; Shig Doi oral history in John Tateishi, And Justice for All: An Oral History of the Japanese American Detention Camps (New York: Random House, 1984), 159.

- ↑ Pacific Citizen , February 17, 1945, 1 [Fowler], February 24, 1945, 1 [Fresno and Selma], March 3, 1945, 2 [Visalia and Lancaster], March 10, 1945, 1 [Delano and San José], March 17, 1945, 1 [Delano], March 31, 1945, 1 [Madera].

- ↑ Pacific Citizen , April 28, 1945, 1.

- ↑ Edward H. Spicer, Asael T. Hansen, Katharine Luomala, and Marvin K. Opler, Impounded People: Japanese Americans in the Relocation Centers (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Interior, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1946. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1969), 259.

- ↑ Pacific Citizen , April 28, 1945, 3 [special agent], July 14, 1945, 2 and July 21, 1945, 5 [reward], May 12, 1945, 6 and May 26, 1945, 5 [editorials], May 26, 1945, 2 [example of group assisting Nikkei], June 2, 1945, 1 and July 28, 1945, 7 [arrests], August 11, 1945, 1 [federal charges]. The Doi defendants would eventually be acquitted of the federal charges as well [ Pacific Citizen , October 13, 1945, 2].

- ↑ Audrie Girdner and Anne Loftis, The Great Betrayal: The Evacuation of Japanese-Americans during World War II (New York: Macmillan, 1969), 399–402. Pacific Citizen , June 30, 1945, 3 [shooting into home of WRA official], March 17, 1945, 3 [Pauling incident], March 10, 1945, 6 [Chinese and Filipino American mistaken identity cases], November 10, 1945, 1 and November 24, 1945, 1 [murder cases].

Last updated Dec. 21, 2023, 3:41 a.m..

Media

Media