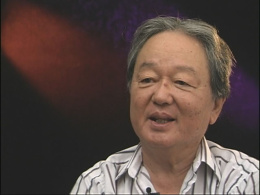

William Hohri

| Name | William Hohri |

|---|---|

| Born | March 13 1927 |

| Died | November 12 2010 |

| Birth Location | San Francisco, CA |

| Generational Identifier |

Writer, civil rights activist and lead plaintiff in the National Council for Japanese American Redress (NCJAR) class action lawsuit. William Hohri (1927–2010) spearheaded the NCJAR class action lawsuit, which sued the U.S. government for $27 billion for injuries suffered as a result of the exclusion and imprisonment of Japanese Americans in U.S. concentration camps during World War II. The long court battle began on March 16, 1983, and ultimately was disallowed on technical grounds on Oct. 31, 1988, two months after the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 was signed. [1]

Before the War

William Minoru Hohri was born to Daisuke and Asa Utsunomiya Hohri in San Francisco on March 13, 1927, the youngest of six children. His parents were Protestant Christian missionaries who had immigrated to the United States in 1922. Hohri became sensitized to racial issues at a young age through his two oldest brothers and older sister. Although all three siblings were raised in the U.S., they were born in Japan, and were forced to live restricted lives in the U.S. due to racist laws that, for example, prevented them from becoming naturalized U.S. citizens, owning land or voting.

In 1930, Hohri's parents contracted tuberculosis and were hospitalized at the Olive View Sanitarium in the San Fernando Valley. The older children were split up and sent to live with different families, while William, 3, and brother Sohei, 5, went to live at the Japanese Children's Home of Southern California, often referred to as the Shonien, which took in Japanese American orphans or children whose parents could not take care of them. About a year later, another brother, Takuo, joined William and Sohei at the Shonien.

War Years

Three years later, the family was reunited, and they initially lived in Sierra Madre for two years. The family moved several more times in the Southern California area before settling in North Hollywood when Pearl Harbor was attacked on Dec. 7, 1941.

Hohri's father, a Christian minister who made his living at a nursery shop, was picked up by the FBI within hours of the Pearl Harbor attack. The father was sent to the Department of Justice Camp at Fort Missoula , Mont., before being reunited with his family months later at the Manzanar War Relocation Authority camp.

Hohri was fourteen years old and in the 10th grade at North Hollywood High when the U.S. government forcibly removed all people of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast. The Hohri family were sent directly to Manzanar in April 1942. Their address became 10-4-2 Manzanar. Hohri graduated from Manzanar High, the makeshift camp school, in June 1944, and shortly thereafter was given leave clearance to head out to Madison, Wisconsin.

In March 1945, Hohri returned to Manzanar where his parents were still imprisoned. He had hoped to tell his parents not to relocate to Madison because jobs were scarce, but instead, Hohri was jailed for traveling without a travel permit, despite the fact that the U.S. government had lifted the exclusion order for Japanese Americans in January 1945. At gunpoint, Hohri was issued an individual exclusion order, requiring him to leave the State of California by midnight that same day.

Postwar Activism

In 1949, Hohri graduated from the University of Chicago while working full time to pay for his college tuition. He married Yuriko Katayama in 1951, and the couple honeymooned in New Orleans, where they became conscious of the Whites Only/Blacks Only segregation issue. Once the couple returned to Chicago, Hohri found a job as a computer programmer but the issue of discrimination was never far from his mind.

The couple became active members of the United Methodist Church (UMC), and Hohri took part in civil rights marches and anti-war rallies against the Vietnam War. Hohri's participation in UMC's governing structure was a good training ground for his future involvement in the redress movement. He represented his Chicago church at a march organized in the Deep South by James Meredith, an African American who broke the color line when he was admitted to the University of Mississippi. Hohri was one of the few Japanese Americans participating in the march.

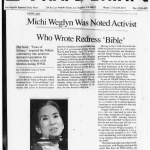

During the 1970s, Hohri and Nelson Kitsuse worked through the UMC to support the national movement to seek a presidential pardon for Iva Toguri , who had been tried, convicted of treason and served a 10-year prison term for being "Tokyo Rose." They dubbed their campaign "Pardon me, Iva." Toguri received a pardon in 1977 by President Gerald Ford on his last day in office.

Following on the heels of the successful Toguri presidential pardon campaign, Hohri and Kitsuse hoped a similar situation would occur with the redress movement , which was gaining national momentum. Starting again from the local church level, Hohri submitted a resolution that backed JACL's redress initiative, calling for a redress bill. However, JACL's National Committee for Redress changed their support from pushing for redress legislation to backing a bill for a study commission. To Hohri, this was a throwback to JACL's wartime accommodationist stand, which favored, above all else, a good public image to gain mainstream acceptance.

Hohri and his church opposed the study commission and stayed the course, calling for direct redress legislation. He was joined by a group from Seattle that included Frank Abe, Frank Chin, Chuck Kato, Rod Kawakami, Ron Mamiya, Mitch Matsudaira, Henry Miyatake , Tomio Moriguchi, Shosuke Sasaki , Emi Somekawa and Kathy Wong, along with Karen Seriguchi from San Francisco.

It was in Seattle that the group came up with the name for a new redress organization, the National Council for Japanese American Redress. New wording for the UMC's resolution was adopted from Shosuke Sasaki's legislative proposal. Two weeks after meeting the Seattle group, Hohri agreed to lead the newly formed group and thus, NCJAR came into existence in May 1979. Hohri adopted Frank Fujii's "ichi-ni-san" barbed wire logo from Seattle's Day of Remembrance for NCJAR's newsletter masthead.

The NCJAR's focus eventually turned to a class action lawsuit that wound its way through the courts and had a hearing by the Supreme Court. Despite being rejected by the Supreme Court, some observers feel that the suit may have influenced the ultimately successful passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988.

In addition to the NCJAR newsletter, Hohri put out The Epistolarian newsletter and was part of an informal group of writers who called themselves the Asian American Literary Arts Society.

Return to California

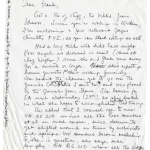

Hohri never forgot the individual exclusion order he received during the war, and when he and Yuriko decided to move back to California in the early 1990s, he wrote a letter to the Secretary of the Interior, wondering if he was permitted to return to California. Hohri never expected a response and none was given.

In his later years, Hohri continued to conduct research and write. In particular, Hohri pursued research on the draft classification issue and whether the U.S. government violated the Selective Service Act of 1940 by drafting Japanese Americans males from what essentially was a prison camp. He also utilized his computer skills to reformat Deborah Lim's report on JACL's wartime activities to make it easier for readers.

In the Rafu Shimpo newspaper, Hohri wrote a regular column titled, "Rambler's Nemesis," which was the same name as a column published in the Sangyo Nippo newspaper before the war by his brother, Sam, who died from tuberculosis in 1947.

Books published by Hohri include Repairing America: An Account of the Movement for Japanese-American Redress (1988), Resistance: Challenging America's Wartime Internment of Japanese-Americans (2001), and Manzanar Rites, A Novel (2002).

Hohri passed away on November 12, 2010, after a brief battle with Alzheimer's.

For More Information

Axford, Roger W. Too Long Silent: Japanese Americans Speak Out . New York: Media Publishing and Marketing, Inc., 1986.

Hohri, William. "Redress as a Movement Towards Enfranchisement." In Japanese Americans: From Relocation to Redress , edited by Roger Daniels, Sandra C. Taylor, and Harry H. L. Kitano: 196–99. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1991.

———. Repairing America: An Account of the Movement for Japanese-American Redress . Pullman: Washington State University Press, 1988.

———. "Afterword." In Only What We Could Carry: The Japanese American Internment Experience , edited by Lawson F. Inada. Berkeley: Heydey Books, 2000.

———. Resistance: Challenging America's Wartime Internment of Japanese-Americans . Lomita, Calif.: The Epistolarian, 2001.

———. Manzanar Rites: A Novel . Lomita, Calif.: The Epistolarian, 2001.

Murray, Alice Yang. Historical Memories of the Japanese American Internment and the Struggle for Redress . Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008.

Footnotes

- ↑ Sources for this article include e-mail correspondence with William Hohri and Frank Abe; conversations with Yuriko Katayama Hohri, daughter Sylvia Hohri, and brother Sohei Hohri; and the Densho interview with William Hohri.

Last updated April 8, 2024, 2:38 a.m..

Media

Media