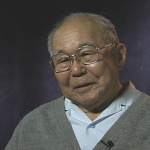

Tamotsu Shibutani

| Name | Tamotsu Shibutani |

|---|---|

| Born | October 15 1920 |

| Died | August 4 2004 |

| Birth Location | Stockton, California |

| Generational Identifier |

Tamotsu Shibutani was one of the Japanese American researchers who worked for the Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study (JERS) under Dorothy S. Thomas. As was the case with these Nisei workers, Shibutani was in a double role of researcher and inmate and frustrated by aspects of the study in part because of the absence of any clear methodology. After the war, Shibutani earned a doctorate and reputation as a well-respected sociologist. While he dealt with a range of topics during his long career, he did return to his wartime notes on at least two occasions to write about incarceration on his own terms.

Early Life

Born in 1920, Shibutani had been interested in aspects of race since the mid-1930s, when he experienced discrimination as a youth in Stockton, California. A capable student and avid reader, he pursued an interest in race and human relations from the outset of his academic career, first at Stockton Junior College and then at Berkeley, where he majored in sociology and philosophy. Before meeting Thomas at Berkeley, however, Shibutani was heavily influenced by his Issei father Naonosuke, who was also an intellectual. By the time Shibutani was in high school he had become keenly aware of racial discrimination, especially against Japanese immigrants in central California. He asked his father what to study to learn about race relations, and his father suggested sociology. As a result, by high school, Shibutani was already reading the work of key sociologists as well as that of Freud, who piqued his interest in psychology. While at Stockton Junior College, Shibutani read John Steinbeck's Grapes of Wrath , and according to John Baldwin, "Tom dreamed of writing such a novel that would help the Japanese Americans as Steinbeck had helped the Okies." By 1939, moreover, Shibutani read John Dewey's How We Think (1910), which confirmed in him a general affinity for pragmatist sentiment. He felt that this philosophical stance was the best for identifying and solving problems, both personal and social. Furthermore, he believed that it was flexible, because it recognized that "all knowledge is hypothetical and open to challenge, further investigation, and further reconstruction." As would become evident in Shibutani's later writings, he embraced the idea that pragmatisism focuses not only on problems but solutions. From his perspective, sociological pragmatism thus created an opening for intellectuals not only to understand the cause of racial tensions, but also to offer up possible mechanisms for resolution. [1]

By the time Shibutani transferred to the University of California, Berkeley, he realized he did not possess the writing skills that would allow him to produce the great Japanese American novel, but he was still committed to pragmatism as an alternative foundation for writing about race relations. [2] As a result of the Second World War, however, Shibutani's university education would be interrupted. Eventually, he would return to university life and earn doctorate in sociology from the University of Chicago but not until several years after the war's end.

Descriptions of Wartime Experience and JERS

In 1942, Shibutani and his family reported to the Tanforan Assembly Center . He eventually went to Tule Lake where he would work until 1944 for Dorothy S. Thomas who was conducting one of the main studies (JERS) about wartime incarceration. A student of Thomas's at U.C. Berkeley, Shibutani had made a positive impression, and she therefore arranged to have him assist her with JERS. In addition to knowing that Shibutani had basic research skills, Thomas realized that she needed "insiders" to collect information for her study—information that only Japanese American inmates could obtain through direct observation and contact with fellow prisoners. Even under suboptimal conditions, Shibutani was glad to have a chance to have some connection with intellectual life and to continue to work with one of his former U.C. Berkeley professors.

As did many of the other JERS participant observers, Shibutani had a complex relationship with Thomas. She was simultaneously academic mentor, friend, director of the study and wife of a central authority in sociology (W.I. Thomas). And yet, as unequal as the power relationship was and despite his appreciation for the personal aspects of their relationship, Shibutani's priority was to advance a practical understanding of the experience of wartime prisoners that would build on a more applicable sociological model. As Yuji Ichioka first established, several Japanese American researchers pressed Thomas for clarification concerning both the objectives and method of study. [3] Shibutani in particular did not want to simply record every little detail of life at Tule Lake; he wanted to find the theoretical framework best suited for understanding his predicament and subject. Notably, Shibutani was willing to challenge his academic mentor despite his simultaneous role as student and inmate. Indeed, that willingness reveals a scholar whose academic pursuits were driven by something other than professional survival, specifically the desire to explain the dynamic nature of belonging. It in fact was an extension of his interest in race relations (originating from his experiences with racism in Stockton) and sociological method that appealed to him in the first place.

After the war, Shibutani started doctoral work in sociology at the University of Chicago at the urging of W.I. and Dorothy Thomas. He studied with Louis Wirth, Everett Hughes, and Herbert Blumer, whose own ideas about sociological method greatly influenced Shibutani's future work on descriptions of Japanese American experience. [4] He also continued to study the work of Herbert Mead, having discussed Mead's work with S. Frank Miyamoto when the two worked together as participant observers at Tule Lake. Although he was graduate student, he continued his work for Thomas, shifting his focus to studying Japanese Americans who were resettling in Chicago during and after the war.

After Shibutani finished his doctoral studies in 1948, the University of Chicago offered him a job to study and teach sociological pragmatism there for three years, after which time he took a job at the University of California at Berkeley. Unfortunately for Shibutani, Berkeley had just finished a long, tense battle dealing with the combination of comparative history and sociology into a single department. [5]

Postwar Career and Scholarly Descriptions of Wartime Experience

Despite the administrative and diplomatic problems he encountered, Shibutani used his time both at Chicago and at Berkeley to think and write about Symbolic Interactionism (SI). He was now free from the constraints imposed by Thomas and JERS, and armed with the necessary tools and resources for designing his own studies of race relations. He used SI both to review earlier academic descriptions of the wartime experience and to make significant contributions to the field of sociology. As a result of his postwar understanding of social scientific practice and the ability to work as a principal investigator, Shibutani produced two foundational texts, neither of which deals primarily with incarceration of Nikkei, but both of which are inspired and informed by the conflicts of 20th-Century Japanese American experience: Improvised News: A Sociological Study of Rumor (1966), which treated rumor as a barometer of shifting social configurations, and The Derelicts of Company K: A Sociological Study of Demoralization (1978), which examined tension within groups and its relationship to social disincorporation.

Though published well before The Derelicts of Company K , Improvised News is perhaps the subtlest example of how incarceration shaped Shibutani's postwar work and how he, in turn, influenced the sociological view of individuals in society. It therefore deserves especially close attention. Basing his work in part on the observations and field notes he had made on behalf of JERS, Shibutani was able to mate his earlier interest in social cohesion and disjunction to a fascination with rumors that he developed while at Tule Lake. The result is a text that tracks impromptu social reconfiguration. Tracing these behavioral patterns, Shibutani hoped, would ultimately reveal "some of the processes whereby new social structures come into existence." [6] Although Improvised News uses sixty examples of situations involving rumor, the motivation and analysis for the larger argument of the book comes from the mere four case studies Shibutani conducted regarding Japanese Americans and wartime experience. [7]

In 2004, Shibutani died at the age of 83 in Santa Barbara, California, after a long and distinguished career at the University of California, Santa Barbara in the Department of Sociology. While he published numerous books and articles—publications that advanced the method of Symbolic Interactionism more generally—his work was informed by his personal experiences with race relations, including his wartime incarceration.

For More Information

Baldwin, John. "Advancing the Chicago School of Pragmatic Sociology: The Life and Work of Tamotsu Shibutani." Sociological Inquiry 60.2 (2001): 115–26.

Hirabayashi, Lane. The Politics of Fieldwork: Research in an American Concentration Camps . Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1999.

Ichioka, Yuji, ed. Views from Within: The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study . Los Angeles: Asian American Studies Center, University of California, Los Angeles, 1989.

Inouye, Karen. "Japanese American Wartime Experience: Tamotsu Shibutani and Methodological Innovation," 1935–1978." Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences (2012): 318-38.

Shibutani, Tamotsu. Improvised News: A Sociological Study of Rumor . Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1966.

---. The Derelicts of Company K: A Sociological Study of Demoralization . Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978.

Yu, Henry. Thinking Orientals: Migration, Contact, and Exoticism in Modern America . New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Footnotes

- ↑ Information on Shibutani's early life and thinking comes from John Baldwin, "Advancing the Chicago School of Pragmatic Sociology: The Life and Work of Tamotsu Shibutani," Sociological Inquiry 60.2 (2001): 115–26. Direct quotes come from page 117.

- ↑ Baldwin, "Advancing the Chicago School," p. 121.

- ↑ Yuji Ichioka, Views from Within: The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study (Los Angeles: Asian American Studies Center, University of California, Los Angeles, 1989).

- ↑ Baldwin, "Advancing the Chicago School," p. 119.

- ↑ Stephen O. Murray, "The Rights of Research Assistants and the Rhetoric of Political Suppression: Morton Grodzins and the University of California Japanese-American Evacuation and Resettlement Study," Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences 27.2 (April 1991): 130–56.

- ↑ Tamotsu Shibutani, Improvised News: A Sociological Study of Rumor (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1966): v–vi.

- ↑ Shibutani, Improvised News , vii.

Last updated Jan. 16, 2024, 2:07 a.m..