Fort Snelling

Sitting on land near the convergence of the Mississippi River and the Minnesota River, Fort Snelling served as a military installation for the U.S. military from the early 19th century to the end of World War II. During World War II, the Military Intelligence Service Language School was housed at Fort Snelling from 1944 to 1946. Located near the Twin Cities—St. Paul and Minneapolis—in Minnesota, Fort Snelling sits on 300 acres and now serves as a space for the Minnesota Historical Society.

Originally called Fort Saint Anthony and constructed in 1820, the fort was renamed Fort Snelling in 1825 during the wars between U.S. military forces and Native American tribes. In the 19th century, Fort Snelling served as a "citadel in the wilderness" because it provided military protection for the Western frontier of the ever-expanding U.S. [1] During World War II, almost three hundred thousand young men entered the U.S. Army and made their way to the front through Fort Snelling. For Japanese Americans, Fort Snelling served as one of the military installations for the training of Japanese language interpreters, interrogators, and personnel in order to fight the Japanese militaristic forces in the Pacific Theater.

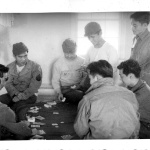

During World War II, the Military Intelligence Service Language School was housed at the Presidio in San Francisco, Camp Savage in Minnesota, and relocated to Fort Snelling in Minnesota in August 1944. At Fort Snelling, Colonel John F. Aiso and Colonel Kai E. Rasmussen both oversaw the military personnel and implementation of the MISLS. [2] Although since 1941 MISLS had taught only Japanese language, in 1944 at Fort Snelling, the MISLS established a Chinese language program in order to assist military forces on the South China coast. [3] Furthermore, the MISLS at Fort Snelling allowed for Nisei women in the Women's Army Corps to receive language training to serve as interpreters and translators. [4] By 1945, the school at Fort Snelling focused its training of linguists for the expected invasion and occupation of Japan. The school had graduated 2,078 Nisei by July 31, 1945 while 1,863 were still in training. [5] After World War II in June of 1946, the Military Intelligence Service Learning School was relocated from Fort Snelling to Monterey, California.

Spark Matsunaga , an AJA from Hawaii who was a member of the 100th Battalion and later became a Senator from the State of Hawaii, was assigned and reported to Fort Snelling on October 3, 1944. The War Relocation Authority approached Matsunaga, who was recuperating from his battlefield injuries, and asked him to speak to pacify anti-Japanese sentiments throughout the Midwest. While stationed at Fort Snelling, Matsunaga gave over 800 speeches, including speaking engagements in front of the soldiers and officers at the military base. [6] One of the main points that Matsunaga conveyed in his speeches was that the men of the 100th Battalion/ 442nd Regimental Combat Team fought "because they had to prove that they were worthy to be called American." [7]

The Fort Snelling National Cemetery holds the remains of soldiers from each of the wars that the U.S. engaged in throughout its history. In the earliest years of the cemetery, it was primarily used for those soldiers who died while stationed at Fort Snelling. Today, Fort Snelling National Cemetery is the final resting place for almost 170,000 servicemen and servicewomen. [8] George Tadashi Tani, who was incarcerated at Minidoka and volunteered for the Military Intelligence Service , was stationed at Fort Snelling from 1944-45. When Tani graduated from the MISLS, he joined U.S. occupation forces in Tokyo and served as a translator. After the war, Tani received his medical degree and opened up a private practice in the Twin Cities. In 1999, Tani passed away and was buried at Fort Snelling National Cemetery. [9] Due to the fact that Fort Snelling served as a language school for the Nisei in the MIS, there were not many deaths and the majority of the Nisei did not have a strong affinity with Minnesota, which influenced their decisions of where to be buried. In comparison, Arlington National Cemetery and the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific (Punchbowl Cemetery) has been a final resting place for the majority of Nisei veterans who served in World War II. [10]

Following World War II, the language school was relocated to Monterey, California, and recruits for the occupation of Europe and Japan were processed at surrounding locations like Fort McCoy in Wisconsin. Fort Snelling as a military installation and garrison closed its post headquarters on October 15, 1946. Since then, Fort Snelling has been utilized as a space for the Veterans' Administration, Bureau of Mines, Department of Natural Resources, General Services Administration, U.S. Army Reserve, and the Minnesota Historical Society. [11]

For More Information

Chicoine, Stephen. Our Hallowed Ground: World War II Veterans of Fort Snelling National Cemetery . Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2005.

Fort Snelling National Cemetery. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

Fort Snelling State Park. National Park Service.

Halloran, Richard. Sparky: Warrior, Peacemaker, Poet, Patriot—A Portrait of Senator Spark M. Matsunaga . Honolulu: Watermark Publishing, 2002.

Historic Fort Snelling. Minnesota Historical Society.

Jones, Evan. Citadel in the Wilderness: The Story of Fort Snelling and the Old Northwest Frontier . New York: Coward-McCann, Inc., 1966.

McNaughton, James C. Nisei Linguists: Japanese Americans in the Military Intelligence Service during World War II . Washington D.C.: Department of the Army, 2007.

Footnotes

- ↑ Evan Jones, Citadel in the Wilderness: The Story of Fort Snelling and the Old Northwest Frontier (New York: Coward-McCann, 1966).

- ↑ James C. McNaughton, Nisei Linguists: Japanese Americans in the Military Intelligence Service during World War II (Washington D.C.: Department of the Army, 2007): 299-304.

- ↑ McNaughton, Nisei Linguists , 315.

- ↑ McNaughton, Nisei Linguists , 316–17.

- ↑ McNaughton, Nisei Linguists , 329.

- ↑ Richard Halloran, Sparky: Warrior, Peacemaker, Poet, Patriot—A Portrait of Senator Spark M. Matsunaga (Honolulu: Watermark Publishing, 2002): 48-50.

- ↑ Halloran, Sparky , 49.

- ↑ Stephen Chicoine, Our Hallowed Ground: World War II Veterans of Fort Snelling National Cemetery (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2005): xvii-xx.

- ↑ Chicoine, Our Hallowed Ground , 238–41.

- ↑ Kathryn Shenkle, "Patriots Under Fire: Japanese Americans in World War II," U.S. Army Center of Military History, accessed on April 28, 2014.

- ↑ Stephen Osman, "Fort Snelling's Last War," Minnesota Historical Society website, accessed on April 28, 2014.

Last updated Jan. 13, 2024, 3:16 a.m..