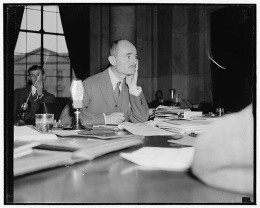

Francis Biddle

| Name | Francis Biddle |

|---|---|

| Born | May 9 1886 |

| Died | October 4 1968 |

| Birth Location | Paris, France |

Wartime attorney general, Nuremburg Trials judge, and writer. Francis Biddle's (1886-1968) Justice Department initially opposed the mass removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast states, but external pressures and internal politics led to a conflict with the Western Defense Command and the War Department over the issue. Eventually Biddle approved Executive Order 9066 , a decision he would regret later in life.

Before the War

Francis Biddle was born on May 9, 1886, the third of four sons of Algernon Sydney Biddle, a law professor at the University of Pennsylvania and Francis Robinson Biddle while the family was in Paris due to his father's poor health. After his father died in 1892, the family lived in Switzerland for two years before returning to the U.S. Francis attended Groton Academy in Massachusetts, then Harvard, where he graduated cum laude in 1909 and received his law degree in 1911.

Out of law school he became the secretary for Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes before becoming a corporate lawyer in Philadelphia for twenty-three years. In 1918, he married the poet and essayist Katherine Garrison Chapin Biddle (1890–1977). The couple had two sons, Edmund Randolph (1921–2000) and Garrison Chapin (1923–30). Despite his Republican roots, he grew disillusioned with the party over labor issues and campaigned against Herbert Hoover in 1932. His support and interest in labor issues led to his appointment by President Franklin D. Roosevelt as chairman of the National Labor Relations Board in 1934. After a return to his law practice, he became chief counsel for a congressional investigation into corruption allegations against the Tennessee Valley Authority, charges that he helped to disprove. The President went on to appoint him a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals in 1939, solicitor general in 1940, then attorney general in 1941. At the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor, he had been attorney general for only three months.

Wartime Attorney General and the Road to Executive Order 9066

Soon after taking office, Biddle found himself dealing with enemy alien related issues. The Justice Department had already built a series of internment camps for enemy aliens and held some 2,000 German and Italian nationals in custody. Biddle also testified in favor of H.R. 3, the "Hobbs Concentration Camp Bill," which called for an expansion in the ability to detain aliens without hearings or due process. (The bill did not pass.) [1]

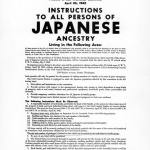

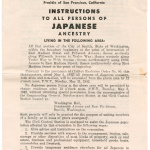

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Biddle's Justice Department carried out the initial roundup of enemy aliens on the ABC list . Using FBI agents and local law enforcement, 2,300 enemy aliens were arrested by December 10, of which some 1,300 were Japanese. [2] Though noted as a civil libertarian, many of the initial actions of the Justice Department belied that reputation. On December 8, the Justice Department closed the borders with Canada and Mexico to "all persons of Japanese ancestry, whether citizen or alien," what Roger Daniels cites as the "the very first act of wartime discrimination against citizens." [3] Later in December, the Justice Department approved searches of any household where an Issei lived without a warrant "where the time is insufficient in which to procure a warrant"; hundreds of households were raided as a result, with Biddle later admitting that little of note was discovered in these searches. [4] Biddle did also issue a press release on December 10 calling for an orderly roundup and for other Americans not to mistreat resident Japanese Americans.

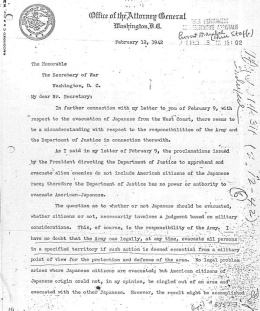

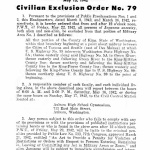

Over the next six weeks, Biddle's Justice Department would butt heads with the War Department and Western Defense Command over the Japanese American issue. At an early January meeting with John DeWitt , head of the Western Defense Command, Biddle agreed to the establishment of Category A zones around important military related facilities from which enemy aliens could be excluded. Two weeks later, on January 24, Biddle received the zone plan from Secretary of War Henry Stimson , which he approved, since it involved only aliens and would move out only 7,000, 3,000 of whom were Japanese.

But DeWitt's Western Defense Command—aided by growing pressure from West Coast journalists and politicians—pressed for harsher measures. Hoping to head these off, Biddle called a meeting with the War Department leaders on February 1 at which he proposed a joint press release issued in the two departments stating that "the present military situation does not at this time require the removal of American citizens of the Japanese race" and "that appropriate steps have been and are being taken." The meeting turned contentious, with his aides, Edward Ennis and James Rowe , clashing with solicitor general Allen Gullion and his assistant Karl Bendetsen . Assistant Secretary of War John McCloy refused the proposal pending DeWitt's response; by then a convert to a plan to remove all Japanese Americans including American citizens, DeWitt refused cooperation.

The attacks on Biddle continued. Nationally syndicated columnist Henry McLemore wrote that Biddle wouldn't be elected "third assistant dog catcher" in California and that "Californians have the feeling that he is the one in charge of the Japanese menace, and that he is handling it with all the severity of Lord Fauntleroy." [5] California Congressman Leland Ford threatened that if Biddle didn't approve mass removal of Japanese Americans, "I would drag the whole matter out of the floor of the House" and that they would "clean the god damned office out in one sweep." [6] Before a Senate committee headed by Senator Monrad Wallgren of Washington, Biddle reiterated his opposition to mass removal but also left the door open by stating that the "military must determine the risk and undertake the responsibility for evacuation of citizens of Japanese descent." [7] He also lunched with the President on February 7, again reiterating his opposition to mass removal.

After his lunch with FDR, Biddle asked Interior Department lawyer Benjamin V. Cohen for a legal opinion on mass removal of Japanese Americans. Cohen's subsequent memo argued that military factors outweighed any constitutional protections; "In times of national peril any reasonable doubt... must be resolved in favor of action to preserve the national safety." [8] On February 17, Biddle wrote a final memo to FDR reiterating his opposition to mass removal at which time the President informed him that had already granted approval to Stimson, ending Biddle's opposition. Later that day, at a meeting at his house with War Department leaders, he stunned Rowe and Ennis with his announcement that he had earlier agreed to mass removal. Executive Order 9066 followed.

After EO 9066 and Subsequent Career

Biddle remained as attorney general until the death of FDR in 1945. In this role, he was involved in discussions about the fate of Dillon Myer and the War Relocation Authority when that agency came under attack after the Tule Lake riot of late 1943 and the debate about when to allow Japanese Americans to return to the West Coast, taking pragmatic rather than ideological positions each time.

In his 1962 autobiography, he regretted his part in the Japanese American removal and incarceration. His admiration for Stimson and Roosevelt no doubt played a part in his acceptance of the policy they favored. "I was new to the Cabinet," he wrote "and disinclined to insist on my view to an elder statesman [Stimson] whose wisdom and integrity I greatly respected." He also wrote that "decisions were not made on the logic of events or on the weight of evidence, but on the racial prejudice that seemed to be influencing everyone." [9] At the same time, Greg Robinson points out that he was himself not immune to such prejudice, stating in October 1942 that "the Jap is in a class of his own... No one seems to understand the operations of his mind, and he becomes an imponderable quantity." [10] Former aide James Rowe summed it up succinctly in a later oral history: "Frankly, he just folded under, I think." [11]

He resigned after FDR's death and was subsequently appointed a judge at the Nuremberg trials. He later testified in favor of the Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act in 1948. In 1950, he became chairman of the Americans for Democratic Action. He also authored several books, including a novel, a biography of Oliver Wendell Holmes, and two volumes of memoirs. He died of a heart attack on October 4, 1968.

For More Information

Finding Aid to the Francis Biddle Papers. Georgetown University.

Biddle, Francis. In Brief Authority . Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1962. [The second volume of Biddle's autobiography.]

Finding Aid to the Katherine Biddle Papers. Georgetown University.

Daniels, Roger. Concentration Camps, U.S.A.: Japanese Americans and World War II . New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1971.

———. Concentration Camps, North America: Japanese in the United States and Canada during World War II . Malabar, FL: Robert E. Krieger Publishing Co., 1981. [Updated edition of the Concentration Camps U.S.A. whose relevant sections are identical to the earlier book.]

Irons, Peter. Justice at War: The Story of the Japanese American Internment Cases . New York: Oxford University Press, 1983.

Aid to the Japanese American Internment Collection. Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library.

Pennsylvania Center for the Book. "Francis Biddle Biography." Penn State University.

Robinson, Greg. By Order of the President: FDR and the Internment of Japanese Americans . Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001.

Footnotes

- ↑ Greg Robinson, By Order of the President: FDR and the Internment of Japanese Americans (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001), 49–50.

- ↑ Tetsuden Kashima, Judgment Without Trial: Japanese Imprisonment during World War II (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002), 50–51.

- ↑ Roger Daniels, Asian America: Chinese and Japanese in the United States Since 1850 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1988), 204.

- ↑ Daniels, Asian America , 206–08.

- ↑ Roger Daniels, Concentration Camps, North America: Japanese in the United States and Canada during World War II (Malabar, FL: Robert E. Krieger Publishing Co., 1981), 63.

- ↑ Klancy Clark de Nevers, The Colonel and the Pacifist: Karl Bendetsen, Peter Saito and the Incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2004), 91.

- ↑ Peter Irons, Justice at War: The Story of the Japanese American Internment Cases (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983), 52.

- ↑ Irons, Justice at War , 54.

- ↑ Robinson, By Order of the President , 112.

- ↑ Ibid., 171.

- ↑ James H. Rowe, interview in The Earl Warren Oral History Project: Japanese-American Relocation Reviewed: Volume 1, Decision and Exodus (Regional Oral History Office, University of California Berkeley, 1976), 9. http://content.cdlib.org/view?docId=ft667nb2x8&brand=calisphere&doc.view=entire_text .

Last updated Dec. 8, 2023, 8:17 p.m..

Media

Media