Franklin D. Roosevelt

| Name | Franklin D. Roosevelt |

|---|---|

| Born | January 30 1882 |

| Died | April 12 1945 |

| Birth Location | Hyde Park, NY |

The 32nd president of the United States, President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882–1945), signed Executive Order 9066 , which authorized the mass removal of all persons of Japanese descent from the West Coast. Roosevelt then approved their subsequent incarceration in concentration camps. Perhaps blinded by racialized thinking, he was quick to believe unfounded reports of Japanese American espionage and was largely indifferent to the human cost of the policy, failing to appoint a property custodian or issue a timely statement in support of Japanese American loyalty after EO9066. Even after promising to expedite the return of loyal Japanese Americans to their homes, he delayed lifting exlusion for six months in 1944. Almost universally regarded as one of history's greatest and most influential presidents, EO9066 and its aftermath remain a blot on his record.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt was born on January 30, 1882, in Hyde Park, New York. Each of his parents was from a wealthy old New York family, and he grew up in privileged circumstances, attending Groton School and graduating from Harvard in 1904. He married Anna Eleanor Roosevelt (1884–1962; she was his fifth cousin, once removed) in 1905. After serving as a New York state senator (1911–1913) and assistant secretary of the navy (1913-1920), he ran for vice-president on the Democratic ticket in the 1920 national election, but was defeated. Stricken in 1921 by polio, which left him unable to walk, he spent much of that decade attempting vainly to recover the use of his legs. After serving as governor of New York (1929–32) he was elected president in 1932. During his unprecedented twelve years in office, he was renowned for his direction of New Deal programs to fight the Great Depression and then for his leadership during World War II.

Prewar Attitudes Towards Japanese

From the beginning, Roosevelt's attitudes towards Japan and Japanese Americans were shaped equally by his cosmopolitan family life and the Social Darwinist racial attitudes of his time. He had a number of friends and acquaintances who were Japanese and family members who had visited Asia, most notably his mother, who had accompanied her merchant father to China. He was greatly influenced by his distant cousin Theodore Roosevelt, who admired the Japanese but viewed Japan as a military threat. The young Franklin Roosevelt was also greatly influenced by author and navy booster Alfred Thayer Mahan, whom he discovered at age eleven, and by author Homer Lea, who viewed Japanese immigration as a catalyst for war in the Pacific. During his stint as assistant secretary of the navy in the Woodrow Wilson administration, FDR warned repeatedly of the need to protect the West Coast from Japanese attack. In his 1920s writings, he called for peaceful engagement with Japan but favored exclusion and alien land laws for Japanese immigrants based on their supposedly innate and incompatible racial characteristics.

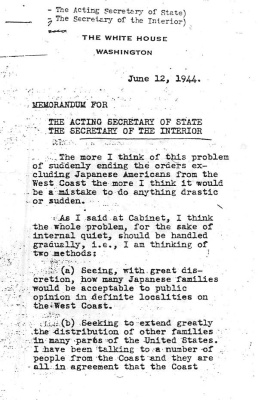

During the 1930s, FDR hardened his stance on Japan due largely to Japan’s naval buildup and aggression against China, and in the process on Japanese Americans, whom he suspected of loyalty to Tokyo. After a 1936 Joint Planning Committee report on Hawai'i and the Japanese population there, he wrote a memo stating in part:

One obvious thought occurs to me—that every Japanese citizen or non-citizen on the Island of Oahu who meets these Japanese ships or has any connection with their officers or men should be secretly but definitely identified and his or her name placed on a special list of those who would be the first to be placed in a concentration camp in the event of trouble. [1]

Subsequently, further surveillance was undertaken on the West Coast Japanese population, but not on resident German and Italian populations.

The Road to Executive Order 9066

With war approaching, Roosevelt sought information on Japanese Americans from government intelligence agencies. He meanwhile hired his friend John Franklin Carter to conduct secret intelligence gathering activities on a variety of topics, one of which was the Japanese American situation. Carter in turn hired businessman Curtis Munson, whose investigations of Japanese communities on the West Coast and in Hawai'i found little threat from Japanese Americans. (See Munson Report .) Other intelligence confirmed these findings. Whatever evidence his intelligence provided, it was not enough to overcome FDR's racially-informed propensity to believe the worst about Japanese Americans.

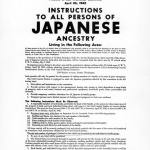

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt granted Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox 's request to visit Hawai'i to investigate firsthand. After a 36-hour visit, Knox issued incendiary and widely publicized claims about Japanese American fifth column activity in Hawai'i, which were later proven to be untrue. Meanwhile the President half-heartedly consented to John Franklin Carter’s plan to assist loyal Japanese Americans. Over the next two months, West Coast military commanders, interest groups and politicians built up pressure for the removal of Japanese Americans from the coast. A policy debate took place within Roosevelt's cabinet between the War Department on one side and the Justice Department on the other over the fate of Japanese Americans. Roosevelt ultimately sided with the military, despite Attorney General Francis Biddle’s protests. On February 11, in a phone call with Secretary of War Henry Stimson , Roosevelt give his approval to exclude both aliens and citizens, sealing the fate of Japanese Americans. On February 17, he gave final approval to Stimson and his more gung-ho assistant John McCloy and instructed them to come up with an executive order. On February 19, 1942, he issued Executive Order 9066.

The reasons for Roosevelt's approval of mass forced removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast are complex, and are perhaps best summarized by Milton Eisenhower's assessment that the "President's final decision was influenced by a variety of factors—by events over which he had little control, by inaccurate or incomplete information, by bad counsel, by strong political pressures, and by his own training, background, and personality." [2] Historian Greg Robinson proposes that, beyond his immense burden as Commander-in-Chief, Roosevelt's history of anti-Japanese prejudice and racialized thinking led to a carelessness in judging information about the Japanese American situation and a malign indifference to the rights of Japanese Americans in the face of political pressure for their exclusion. [3] This indifference was best dramatized by his failure to appoint an alien property custodian with the power to take charge of the possessions of West Coast Japanese Americans. As a result, the communities suffered crushing financial losses. Furthermore, despite many requests from figures both within and outside his administration for a statement in support of Japanese Americans, he maintained a long public silence on the issue.

After Exclusion

After EO9066, Roosevelt approved the developing plans for mass confinement of those removed, and on March 18, 1942 signed an Executive Order creating the War Relocation Authority to operate the camps, with Milton Eisenhower (later replaced by Dillon Myer ) as its director. Meanwhile, together with Knox and the Joint Chiefs of Staff, FDR ordered mass confinement of Japanese Americans in Hawai'i. Despite his repeated urgings, Japanese Americans in Hawai'i were mostly spared, thanks to quiet opposition by Military Governor Delos Emmons and Assistant Secretary of War McCloy. Prompted by the War Department chiefs and by Office of War Information director Elmer Davis, Roosevelt did approve the creation of a volunteer Nisei combat battalion. On February 1, 1943, on the occasion of Nisei being allowed into the military, Roosevelt finally issued a widely publicized statement. Authored by Davis and Myer, it read in part, "Americanism is a matter of the mind and heart; Americanism is not, and never was, a matter of race or ancestry." He continued to offer public praise for the exploits of Nisei soldiers.

Given Roosevelt's failing health and the exigencies of directing a worldwide war, his subsequent involvement with Japanese American issues was limited. External pressures and sensational press charges that Myer was "coddling" the inmates led to a chain of events that led Roosevelt to approve his advisors’ plan to move the WRA under the umbrella of the Department of Interior, where Secretary Harold Ickes paid close attention to assisting resettlement. In part to quell this negative publicity, he authorized First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt to make a fact-finding visit to a camp, and at her urging he met personally with Myer. He also issued a ghost written statement in September 1943 promising a return to the West Coast for Japanese Americans "whose loyalty to this country has remained unshaken through the hardships of the evacuation which military necessity made unavoidable." However in subsequent months, Roosevelt acted to delay allowing Japanese Americans to return to the West Coast—even after the army agreed that there was no longer any conceivable military rationale for exclusion. This was partly for election year political purposes, given the continued opposition from West Coast political leaders, and also a product of his sincere belief that Japanese Americans should be "distributed" in small groups around the country to foster assimilation. Three days after his reelection, on Nov. 10, 1944, he agreed to allow Japanese Americans to return to the West Coast if the army would assume responsibility.

Franklin D. Roosevelt died in office on April 12, 1945.

For More Information

"Franklin Delano Roosevelt: A Resource Guide." Library of Congress. http://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/presidents/fdroosevelt/index.html .

Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum. http://www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/ .

Robinson, Greg. By Order of the President: FDR and the Internment of Japanese Americans . Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001.

Morgan, Ted. FDR: A Biography . New York: Simon & Schuster, 1985.

Footnotes

- ↑ Cited in Peter Irons, Justice at War: The Story of the Japanese American Internment Cases (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983), 20

- ↑ Cited in Greg Robinson, By Order of the President: FDR and the Internment of Japanese Americans (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001), 112

- ↑ Robinson, By Order of the President , 123

Last updated June 19, 2020, 4:07 p.m..

Media

Media