Hood River incident

Notorious incident involving the removal of sixteen Nisei servicemen's names from the county "roll of honor" in Hood River, Oregon. The incident on November 29, 1944, was part of a string of anti-Japanese actions taken to try to prevent removed Japanese Americans from returning to the area after World War II. National outrage against the community heightened five weeks later when a local Japanese American serviceman died after completing a heroic mission in the Philippines. Under great pressure, the local American Legion post restored Nisei names to the wall of the county courthouse in April 1945. (See also Return to West Coast .)

Incident

During World War II, the community of Hood River, Oregon, held a national reputation for its support of the war effort. The 11,500 residents in this rural county, along the Columbia River Gorge north of Mt. Hood, were distinctive in the nation for doubling their bond quota during their Fifth War Loan drive; in the next drive, residents led all Oregon counties with sales of $750,000. Hundreds attended war bond rallies at the Victory Center in front of the county courthouse. [1] The local American Legion post also erected a war memorial there, affixing wall plaques that listed the names of more than 1,600 residents serving their country. On the evening of November 29, 1944, Legion Post No. 22 removed the names of sixteen, all Japanese Americans. It did so, it explained, because these young men were dual citizens of Japan and the United States. [2] The veterans' group also protested Nisei serving in the armed forces and proposed an amendment to the U.S. Constitution that would deny citizenship to all Americans of Japanese descent ( Nikkei ). [3]

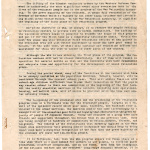

As part of its campaign to deter Japanese Americans from returning to the valley after the war, Legionnaire Kent Shoemaker wrote a series of paid, full-page public notices that appeared in two local newspapers from January through March 1945. With titles such as, "So Sorry Please, Japs are Not Wanted in Hood River," these ads included lists of Japanese landowners and their acreage, with the goal that whites would purchase their properties. Five of the six ads included the names of more than a combined 1,800 locals, under a statement that they were "one hundred percent" behind "efforts to keep the Japs from returning to this county." The second notice added a poem:

Hood River, Golden Valley in the hills,

Who is to possess its acres and its rills?

A horde of aliens from across the sea?

Or—shall it be a Paradise for you and me? [4]

Background

As early as 1900, the Hood River valley, fertile with volcanic ash from Mt. Hood, had earned a reputation for its quality apples, including awards that year at the World's Fair in Chicago. [5] New landowners, eager to clear their heavily forested property, employed Japanese immigrant ( Issei ) laborers who were working for the Mt. Hood Railroad. In exchange for clearing fifteen acres of woods, some landowners enticed Issei by offering five-acre plots of land, typically stumpland or brushland. [6] As a result, Issei in Hood River gradually came to own their own property, and their plots were spread throughout the valley, rather than in colonies, as in many communities. By 1920, three-fourths of Hood River's more than 350 Issei were farmers, and they held more than half the acreage owned by Nikkei in Oregon. In Hood River they also cultivated 75 percent of the valley strawberries, raised as quick cash crops between their apple seedlings. [7]

Success of Japanese farmers in Hood River brought exclusionist sentiments that gained statewide attention. In 1917 Hood River state senator George Wilbur introduced Oregon's first alien land bill to prevent Nikkei from buying property. (Oregon's anti-alien land law passed in 1923.) Two years later locals formed the Anti-Alien Association, vowing to neither sell nor lease land to Japanese and to prevent further immigration of "Asiatics." [8] In 1920 legislator Frank Davey, conducting a study for the governor on the Japanese situation, concluded, "'The Japanese Question' is more acute in Hood River than in any other place in Oregon." [9]

With intensive, cooperative farm practices and involvement of their entire families, Nikkei were becoming successful and enviable farmers. By 1940, when Hood River led the state in the value of its fruit harvest at $2.2 million, Nikkei farms contributed 25 percent of the valley's production, even though they comprised less than ½ percent of the population. [10]

Responses

Newspapers, organizations, and citizens from across the country, as well as military in service, responded quickly to Hood River's honor roll incident, most with contempt. News headlines included "Hood River's Blunder" ( New York Times ), "Not So American" ( Chicago Sun ), and "Dirty Work at Hood River" ( Collier's ). [11] The American Civil Liberties Union, the Portland Council of Churches, and the Hood River Ministerial Association were among organizations condemning the action. [12] Letter writers chastised these "nazi tactics," questioned whether names of GIs with German and Italian names had been removed, and even threatened not to eat Hood River apples again. [13] The Stars and Stripes , a military newspaper, decried the assault on these soldiers, with one GI claiming, "We say they're a helluva lot better, that they've got more guts." [14] 14 Of the more than 300 servicemen who wrote letters to the Hood River News , all but one criticized the action. Three local servicemen even independently requested that their names be removed from the honor roll unless Nisei names were replaced. [15]

Still others favored the Legion's action. Iowa's Bellevue Herald questioned whether "millions of Japs" would buy up the West Coast as Pendleton's East Oregonian accused Japanese of a plan to "out-breed whites." [16] The Pasadena Ban the Japs Committee and the Oregon Anti-Japanese, Inc. offered support. [17] An Oregon state senator exhorted, "Get your heart in America and the Japs out!" [18] Others maintained that "a Jap is a Jap no matter where he was born" and that they "multiply like flies" and "can live on a few handfuls of rice a day." [19] Of the almost 400 letters that Post 22 received, only one-third favored their action. But eight other Legion posts removed Nisei names from their honor rolls too. [20]

Five weeks after Nisei names were removed from the honor roll, on January 3, 1945, Hood River-born Frank Hachiya died in the Philippines, where he had been a linguist with the U.S. Army's Military Intelligence Service . After volunteering to interview a captured Japanese prisoner behind enemy lines, Hachiya was likely mistaken as an infiltrator by American troops. Citizens contrasted his heroism with the community's shame, including a New York Times headline, "Private Hachiya, American" [21] as well as three Florida infantrymen, who criticized the Legion for "knif[ing] fighting men in the back." [22]

In February 1945 American Legion National Commander Edward N. Scheiberling announced that the actions of Post 22 were "ill-considered and ill-advised" and contrary to the organization's ideals. Seven weeks later, on April 9, 1945, the names of fifteen of the sixteen Nisei were repainted. (One of the Nisei had been dishonorably discharged in an incident at Ft. McClellan, Alabama, an action that would not be voided until 1983.) Still, Commander Jess Edington maintained that replacing Nisei names did not change Post #22's stance. [23]

Aftermath

Hood River mayor Joe Meyer discouraged Nikkei from returning home after the war, charging, "Ninety percent are against the Japs." The community attracted national attention as a "plague spot" and "test area" where prejudice ran high. Rumors spread that locals would deter returning Nikkei at the train depot, and some predicted bloodshed. [24] Fears increased as Nikkei saw names of neighbors and friends in newspaper notices discouraging their return. [25]

Once home, veterans and their families could not buy food, furniture, gasoline, or farm equipment at most local stores and were often forced to drive twenty miles away to make purchases. A downtown barber denied a haircut to decorated war veteran George Akiyama, threatening to cut his throat. An army adjutant general took action by pressuring merchants to sell goods to Nikkei or face martial law as a consequence. [26] On their farms, many Japanese Americans found that caretakers gave unfair financial returns and left their farms in deplorable conditions. Despite this, a small group of about fifty citizens, forming the League for Liberty and Justice, offered to shop and drive produce trucks for returning Nikkei families. [27] In all, only forty percent of prewar Nikkei residents returned to Hood River, compared to almost seventy percent in the state. [28]

Worried about his community's unwelcome climate, Frank Hachiya's father finally buried his son at Hood River's Idlewilde Cemetery in 1948, almost three years after his son's death in the Philippines. State and national dignitaries served as honorary pallbearers, including Charles Sprague, former Oregon governor, who had reversed his previous inaction and began advocating for Japanese American civil rights. [29]

Legacy

In the seven decades since World War II, Hood River's economy began embracing tourism and outdoor activities with less emphasis on agriculture. By 2010, its population was almost thirty percent Latino, and Nikkei composed little more than one-half percent (although with mixed-race Japanese, that rose to 1.1%). [30] Residents who experienced the war often chose not to speak about it and newcomers were unfamiliar with their community's past. One local once described the situation as "an eerie crime scene, which nobody dare[d] discuss." [31]

With Hood River's increased cultural and ethnic diversity, greater intermarriage, the involvement of Japanese Americans as active community participants and leaders, [32] and the passage of time, efforts to memorialize the past and pay tribute to Nisei veterans have finally taken place. In 2001 George Akiyama and Mamoru Noji served as grand marshals of the annual Fourth of July parade. That fall on Veterans Day, Post #22 dedicated a brick at the downtown Overlook Memorial Park "in honor of all Nisei veterans." [33] In 2007 more than five hundred attended a Day of Remembrance to "break the silence" of the past. [34] And on Memorial Day in 2011 at Idlewilde Cemetery, the community unveiled a marble monument with engraved names of the sixteen Nisei veterans as well as all Nikkei who had served in the armed forces. [35]

Related Articles

For More Information

Girdner, Audrie, and Anne Loftis. The Great Betrayal: The Evacuation of the Japanese-Americans during World War II . New York: Macmillan, 1969.

Hegwood, Robert Alan. "Erasing the Space Between Japanese and American: Progressivism, Nationalism, and Japanese American Resettlement in Portland, Oregon, 1945—1948." M.A. thesis, Portland State University, 2011.

Robbins, William G. "'The Kind of Person Who Makes This America Strong': Monroe Sweetland and Japanese Americans." Oregon Historical Quarterly 113.2 (Summer 2012): 198–229.

Tamura, Linda. "Ironic Heroes: 'The Enemy's Our Cousin,'" The COLUMBIA , Washington State Historical Society, Spring 2006.

———. Nisei Soldiers Break Their Silence: Coming Home to Hood River . Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2012.

———. "'Wrong Face, Wrong Name': The Return of Japanese American Veterans to Hood River, Oregon, after World War II." In Remapping Asian American History , ed. Sucheng Chan. Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press, 2003. 107–25.

Footnotes

- ↑ Linda Tamura. Nisei Soldiers Break Their Silence: Coming Home to Hood River (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2012), 141.

- ↑ Linda Tamura. "'Wrong Face, Wrong Name': The Return of Japanese American Veterans to Hood River, Oregon, after World War II" in Sucheng Chan, ed., Remapping Asian American History , Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press), 112.

- ↑ Tamura, Nisei Soldiers , 138.

- ↑ Tamura, Nisei Soldiers , 151-53.

- ↑ Tamura, Nisei Soldiers , 19.

- ↑ Tamura, Nisei Soldiers , 20.

- ↑ Tamura, Nisei Soldiers , 22.

- ↑ Tamura, "The Enemy's Our Cousin: Pacific Northwest Nisei in the United States Military Intelligence Service," Columbia , (Spring 2006), 17.

- ↑ Tamura, "Wrong Face," 109-10.

- ↑ Tamura, Nisei Soldiers , 173.

- ↑ Tamura, Nisei Soldiers , 143.

- ↑ Tamura, Nisei Soldiers , 148.

- ↑ Tamura, Nisei Soldiers , 145.

- ↑ Ralph G. Martin, "Legion Post Arouses Ire of 7th's GIs," The Stars and Stripes , January 5, 1945, 2.

- ↑ Tamura, Nisei Soldiers , 145-46.

- ↑ Tamura, Nisei Soldiers , 144.

- ↑ Tamura, Nisei Soldiers , 148.

- ↑ Tamura, "Wrong Face," 114.

- ↑ Tamura, Nisei Soldiers , 148.

- ↑ Tamura, Nisei Soldiers , 147.

- ↑ Tamura, "The Enemy's Our Cousin," 16-17.

- ↑ Tamura, Nisei Soldiers , 155.

- ↑ Tamura, Nisei Soldiers , 153-54.

- ↑ Tamura, Nisei Soldiers , 160.

- ↑ Tamura, Nisei Soldiers , 162.

- ↑ Tamura "Wrong Face," 116, 107, 117.

- ↑ Tamura, Nisei Soldiers , 166-70.

- ↑ Tamura, Nisei Soldiers , 17.

- ↑ Tamura, "The Enemy's Our Cousin," 18; Tamura, Nisei Soldiers , 308-09.

- ↑ In the 2010 census, 139 (0.6%) residents in Hood River identified themselves as Japanese. The number of self-identified mixed-race Japanese was almost double at 251 (1.1%). U.S. Census Bureau, Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data, http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk ). Pew Social Trends, Asian-Americans map data, 6, 2010 http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=5&ved=0CDkQFjAE&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.pewsocialtrends.org%2Ffiles%2F2013%2F04%2Fasian-americans_map-data.xlsx&ei=UrfHVO-GFtDioASFoIG4Cg&usg=AFQjCNFv0glU-PKmMHQy0aMVjf7u1VIt0g&sig2=frb3zVNV3KrnKdHOWkz_ew&bvm=bv.84607526,d.cGU

- ↑ Tamura, Nisei Soldiers , 234-36.

- ↑ Tamura, Nisei Soldiers , 233-34.

- ↑ Tamura, Nisei Soldiers , 254-56.

- ↑ Tamura, Nisei Soldiers, 243-47.

- ↑ Tamura, Nisei Soldiers , 270-72.

Last updated June 9, 2020, 5:59 p.m..

Media

Media