Iva Toguri D'Aquino

| Name | Iva Toguri d'Aquino |

|---|---|

| Born | July 4 1916 |

| Died | September 26 2006 |

| Birth Location | Los Angeles, California |

| Generational Identifier |

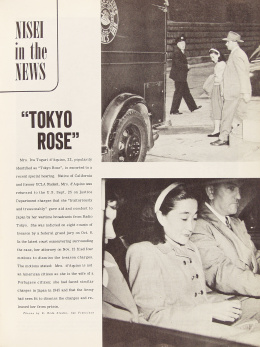

Iva Toguri d'Aquino (1916–2006) was among those

Nisei

visiting Japan before the war who were unable to return once war broke out. She was singled out, accused of being the legendary World War II radio icon "Tokyo Rose," and was tried and convicted of treason after the war. D'Aquino served six years of a ten-year sentence in federal prison. In the 1970s, Japanese Americans convinced of her innocence began a movement that led to a presidential pardon in 1977.

Background

d'Aquino was born Ikuko Toguri in Los Angeles on July 4, 1916. During her school years, she adopted the first name Iva. d'Aquino was raised Methodist and attended grammar schools in Calexico and San Diego before returning with her family to Los Angeles where she went to Compton High School and later Compton Community College. As a young student, she joined the Girl Scouts, played varsity tennis for Compton High, played piano and dreamed of being a medical doctor.

d'Aquino graduated from University of California at Los Angeles in June of 1941 with a degree in zoology. During her college years, peers considered her a popular student and a "loyal American." Her favorite pastimes included sports, hiking, and swing music. d'Aquino, a registered Republican who reportedly voted for Wendell Wilke in 1940, spent much of her time assisting her father in his mercantile shop.

Wartime

The day after her 25th birthday, d'Aquino boarded the Arabia Maru and sailed for Japan from San Pedro, California. The Toguri family sent Iva to care for her Aunt Shizu, who had health issues. The urgency of this trip required a reluctant d'Aquino to leave the country with a "Certificate of Identification" rather than a U.S. passport. During September of that year, d'Aquino attempted to secure a passport for a return trip, but the U.S. stalled her application. Before a passport could be issued, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 , and diplomatic relationships ceased.

Unable to leave Japan during wartime she took Japanese culture classes to improve her ability to communicate. Money earned from teaching piano lessons to neighborhood children paid for her classes.

d'Aquino began to feel the pressure of being an American in Japan during this difficult time. Her aunt began to receive complaints of "harboring an enemy' due to rumors of d'Aquino's pro-American attitude. d'Aquino found work with the Domei News agency and left her aunt's home. She was asked to renounce her American citizenship and refused. As a typist from mid-1942 until late 1943, she barely earned enough to cover housing, and as a result of her poor diet she was hospitalized for six weeks. She took a second job with Radio Tokyo, to cover her medical bills and debts. At Radio Tokyo, she translated English-language scripts drafted for broadcast to the Allied troops in the Pacific. While at Domei, she met Filipe d'Aquino, a Portuguese citizen who was fluent in English and who was three-fourths Japanese. Bonding over shared interests and political views, the couple eventually married.

In November 1943, she reluctantly agreed to announce for Radio Tokyo's "Zero Hour" show. Broadcasted daily, the "Zero Hour" show was part of a Japanese propaganda campaign designed to lower the morale of Allied military forces. Allied POWs were forced to produce the show and they requested that d'Aquino participate in most weekday broadcasts while other women handled weekend shows. Initially she broadcasted anonymously, but eventually was given the name "Orphan Ann."

The "Zero Hour" crew insisted that since their conscription into Radio Tokyo, the Allied POWs and d'Aquino waged a covert campaign to sabotage the Japanese propaganda effort. The use of on-air flubs, innuendo, double entendre, and sarcastic, rushed or muffled readings conjured morale-lifting images of home and spirit. When their Japanese overseers discovered these techniques, the "Zero Hour" crew resorted to mechanical intonations of "reading at gunpoint." From most accounts, these assertions proved accurate. U.S. Army analysis suggested that "Zero Hour" had no negative impact on troop morale and may have improved morale.

Tokyo Rose

Following the Japanese surrender in September 1945, the search for war criminals and Axis military leadership ensued. Allied Forces and news reporters scoured Japan for people of interest. Two of these reporters, Henry Brundidge and Clark Lee, sought out the female radio personality "Tokyo Rose."

"Tokyo Rose" was not any one person, but was a fabricated moniker given by Allied soldiers to any English-speaking woman who was on the radio in the Pacific Theatre. Brundidge and Lee quickly identified d'Aquino as the propagandist. They offered her a significant sum of money, which they later reneged on paying, for an exclusive interview with "Tokyo Rose." Desperate for enough money to return to America, d'Aquino agreed to an interview, unaware of the detrimental consequences of adopting the label of "Tokyo Rose."

In September 1945, after the press had reported that d'Aquino was "Tokyo Rose," U.S. Army authorities arrested her. She spent a year in prison in Japan with limited visits from her husband. The FBI and the Army's Counterintelligence Corps conducted an extensive investigation to determine whether she had committed crimes against the U.S. By the following October, authorities decided that there was insufficient evidence and she was released.

Before the year was out, d'Aquino, who was pregnant, again requested a passport so that she could return to the U.S. American veterans groups and noted broadcaster Walter Winchell learned of this and became outraged that the woman they thought of as "Tokyo Rose" wanted to return. Amidst public furor and political pressure, the Justice Department re-opened the investigation. New witnesses were sought out (who later admitted they were pressured to commit perjury) and d'Aquino was re-arrested in August of 1948.

With new witnesses and evidence, the U.S. Attorney in San Francisco convened a grand jury, and d'Aquino was indicted on a number of counts in September 1948. She was detained in Japan and brought under military escort to the U.S., arriving in San Francisco on September 25, 1948. There, she was immediately arrested by FBI agents, who had a warrant charging her with the crime of treason for adhering to, and giving aid and comfort to, the Imperial Government of Japan during World War II.

d'Aquino's trial began on July 5, 1949, one day after her 33rd birthday. Witnesses supporting d'Aquino were ignored and witnesses detrimental to the case later admitted that the Justice Department forced them to lie in their testimony. On September 29, 1949, a jury found her guilty on one out of eight counts in the indictment. The jury ruled that:

...on a day during October, 1944, the exact date being to the Grand Jurors unknown, said defendant, at Tokyo, Japan, in a broadcasting studio of the Broadcasting Corporation of Japan, did speak into a microphone concerning the loss of ships.

This made d'Aquino, who had gained notoriety as "Tokyo Rose," the seventh person to be convicted of treason in U.S. history. On October 6, 1949, she was sentenced to ten years of imprisonment and fined $10,000 for the crime of treason.

On January 28, 1956, she was released from the Federal Reformatory for Women at Alderson, West Virginia, where she had served six years and two months of her sentence. She successfully fought government efforts to deport her and returned to Chicago, where she worked in her father's shop.

Presidential Pardon

Two petitions (1954 and 1968) for d'Aquino's pardon were denied and despite support from her legal team, including noted civil rights attorney Wayne Collins who worked on the case until his death, she had been unsuccessful in clearing her name.

In the 1970s, Clifford Uyeda of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) became interested in her case. As he found out more about the story of "Tokyo Rose," he rallied the leadership in the JACL to begin a campaign. The JACL National Committee for Iva Toguri was formed in April of 1975. Given the past hurt and injustices suffered by d'Aquino, she was reluctant to trust the JACL's efforts. When she first heard of the interest in her case she said, "Why now, after 30 years? I didn't know what it meant." [1] With the support of Wayne Merritt Collins, the son of her original lawyer, who had since passed away, she agreed to participate in the campaign.

In November of 1975 the JACL printed an informational booklet entitled "Iva Toguri (d'Aquino): Victim of a Legend." A series of positive newspaper articles across the country (including the Denver Post , Chicago Tribune , San Francisco Chronicle , Wall Street Journal and Honolulu Advertiser ) helped to spur interest in the case. On March 22 in 1976, Walter Cronkite featured a sympathetic story about d'Aquino in the CBS Evening News and on June 20, she was featured in a segment of 60 Minutes . The impact of the positive press was tremendous—d'Aquino remarked, "It's a 180 degree turn from twenty-seven years ago." [2]

President Gerald Ford granted her a full and unconditional pardon on his last day in office on January 19, 1977. It was the first and only time such a pardon for treason was ever given. The pardon restored her U.S. citizenship that was taken as a result of her conviction.

Later Years and Legacy

The Toguri case has been the subject of an enormous amount of scholarship with legal scholars, various historians, and both American and Japanese journalists examining both the original case and the 1970s push for a pardon from various angles. Chroniclers of the 1980s Redress Movement have cited Japanese American community mobilization to seek a pardon for Toguri as an important precursor. Her story has received far more attention than the other two Japanese American treason cases, which remain little known. [3]

In 2006, she received the Edward J. Herlihy Citizenship Award for which is given to citizens or veterans for contributions to preserving the legacy of America's service members.

d'Aquino was never reunited with her husband who was forced to return to Japan after her trial. d'Aquino died in Chicago on September 26, 2006.

For More Information

Close, Frederick P. Tokyo Rose/An American Patriot: A Dual Biography . Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press, 2010. Revised and Expanded Edition. Lanham Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2014.

Duus, Masayo. Tokyo Rose: Orphan of the Pacific . Translated by Peter Duus. New York: Kodansha International, 1979.

Hada, John Juji. "The Indictment and Trial of Iva Ikuko Toguri d'Aquino." Thesis, University of San Francisco, 1973.

Howe, Russell Warren. The Hunt for "Tokyo Rose" . Lanham, MD: Madison Books, 1990.

"Iva Toguri d'Aquino and 'Tokyo Rose.'" FBI website.

Kawashima, Yasuhide. The Tokyo Rose Case: Treason on Trial . Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 2013.

Kutler, Stanley I. "Forging a Legend: The Treason of 'Tokyo Rose'." Wisconsin Law Review 6 (1980): 1341-82.

Lipton, Dean. "Wayne M. Collins and the Case of 'Tokyo Rose'." Journal of Contemporary Studies 8.4 (Fall/ Winter 1985): 25-41.

Shibusawa, Naoko. "Femininity, Race and Treachery: How 'Tokyo Rose' Became a Traitor to the United States after the Second World War." Gender & History 22.1 (April 2010): 169–188.

Simpson, Caroline Chung. An Absent Presence: Japanese Americans in Postwar American Culture, 1945-1960 . Durham: Duke University Press, 2001.

Uyeda, Clifford I. A Final Report and Review: The Japanese American Citizens League, National Committee for Iva Toguri . Seattle: Asian American Studies Program, University of Washington, 1980.

Ward, David A. "The Unending War of Iva Ikuko Toguri D'Aquino: The Trial and Conviction of 'Tokyo Rose'." Amerasia Journal 1.2 (1971): 26-35.

Footnotes

- ↑ Clifford I. Uyeda, A Final Report and Review: The Japanese American Citizens League, National Committee for Iva Toguri (Seattle: Asian American Studies Program, University of Washington, 1980), 23.

- ↑ Uyeda, A Final Report , 31.

- ↑ On redress, see Mitchell T. Maki, et al., Achieving the Impossible Dream: How Japanese Americans Obtained Redress (Urbana: Univeristy of Illinois Press, 1999) and Alice Yang Murray, Historical Memories of the Japanese American Internment and the Struggle for Redress (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008). The other two treason cases: Tomoya Kawakita, like Toguri, a Nisei strandee, who was convicted of treason and sentenced to death for mistreating allied POWs in Japan and the Shitara Sisters , convicted of conspiracy to commit treason for aiding German POWs in Colorado.

Last updated Dec. 19, 2023, 5:30 p.m..

Media

Media