Japanese American Hibakusha

Japanese American survivors of the U.S. atomic bombings of Japan. The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 bring to mind the Japanese people devastated by the first nuclear attacks in history. But there are also a considerable number of Japanese Americans who were victimized by the bomb at the end of the Pacific War. These U.S. hibakusha , most of whom currently live in California and Hawai'i, have had a hard time getting recognized in either Japan or America. Similar to the Japanese Americans who were confined in concentration camps during the war, Japanese American bomb survivors remained silent about their suffering for a long time. This has made it a challenge for their experiences to be known and remembered as an important part of Japanese American history.

A Range of Experiences

Although little-known, an estimated 3,000 Japanese Americans—second-generation American citizens—along with several hundred Japanese who became American citizens and residents after migrating to the United States in the 1950s and 1960s, were hibakusha . Hiroshima is the prefecture in Japan that sent the largest number of immigrants to the United States before the war. Nagasaki, too, is among the Southwestern prefectures of Japan that ranked high in the number of residents who migrated to America. Since it was common among first-generation immigrants to send their children to the old country for a few years of education, a number of Japanese American children were in Japan and, indeed, in their parents' hometown of Hiroshima or Nagasaki, when the war broke out in 1941. Although a total figure is impossible to come up with, there were an estimated 11,000 American- and Hawai'i-born people in Hiroshima alone. An unknown number of them died in the bombing. About 3,000 in total survived and returned to the United States after the war from both of the ruined cities. The other group of U.S. survivors, who came to America in the 1950s and 1960s, included "war brides," women who married American men when Japan was under the massive influence of the American military. Also included in this group were those whom we might call "opportunity seekers," Japanese people who came to the United States in order to pursue educational or employment opportunities not readily available in their country still reeling from a war. In 2014, as of this writing, there are about 1,000 known survivors living in the United States.

Together, these hibakusha have formed a unique identity that crossed national boundaries. For example, their wartime memories reveal that their citizenship at the time of the bombing was an incidental result of their families' back-and-forth travels between Japan and America more than a consequence of a carefully calculated decision. The range of individual experiences was surprisingly wide. In some cases U.S.-born survivors who were U.S. citizens in 1945 had no memory of their childhood in America because they came to Japan very young, while in other cases they had clear memories of having difficulty with learning Japanese because their primary language had been English. There were American citizens who eagerly participated in Japan's wartime student mobilization, but there also were those who thought of B-29s as "my friends" or "Angels" because the bombers, too, were from their home country America. [1]

When one of these "friends" from America dropped the bomb, Japanese Americans often relied on, or benefited from, their cross-national backgrounds for survival. For instance, a female survivor in Hiroshima remembers how she was rescued by her friend, a Japanese American girl, when she fainted after the bomb's explosion. The friend, because she had come to know this survivor as another girl from America, dragged her into the bomb shelter. In other instances, Japanese Americans' English-speaking ability gave them privileged access to the occupiers' resources after Japan surrendered. A survivor recalled: "We were lucky, . . . We know a little English, so two soldiers from the Allied Forces came to us. . . . [T]hey got all kinds of food, so we were lucky—we were able to get their food."

Returning to the United States

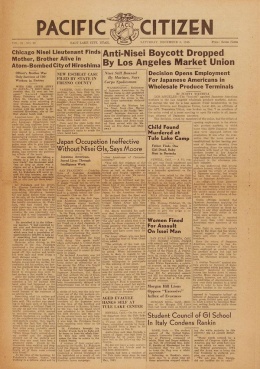

In 1947, Japanese American hibakusha started to return or come to the United States. For many, this meant being reunited with their parents and siblings after long wartime separation. These reunions brought joy, though coming back also brought the trial of readjustment. Some had lost their English during their years in Japan, making it a struggle to continue schooling or gain employment in America. To Japanese people who migrated to America either as "war brides" or "opportunity seekers," post-war U.S. society posed challenges both familiar and unfamiliar. Some faced racism—racial slurs or housing discrimination—for the first time. Worries about their health related to their exposure to the bomb continued to haunt them, especially now that they were far away from families and friends in the country they knew as home. Some felt discriminated against when they told their doctors about their bomb-related illnesses. Unfamiliar with radiation-induced medical conditions, some U.S. doctors even believed that they could be "infected" with these conditions by treating survivors.

The layers of identity, affinity, and experience revealed by these stories contradict the usual view of bomb survivors as Japanese citizens whose national identity explains their experiences. Indeed, because the U.S. hibakusha' s stories go against the grain of these nation-specific understandings of the bomb, their experiences call attention to the history of migration that long preceded the war, and they highlight the nationally un-specific, thus indiscriminate, nature of nuclear attacks. U.S. hibakusha tell us how a simplistic understanding of Americans-as-victors and Japanese-as-victims does not hold. What rings true instead is that the bomb left an indelible mark on both Japanese and American histories.

Even so, the cross-national and cross-cultural impacts of the nuclear disasters did not easily become apparent or accepted. Japanese American survivors during the decades following the war were not outspoken about their experiences, in effect allowing a narrow, nation-specific understanding of the bomb to prevail. Among other things, the Cold War culture fueled an ideology of 100% Americanism, which made it difficult for U.S. survivors to reveal their experiences that connected them to a former enemy state. Within Japanese American communities and families, the bomb could be seen as a symbol of the long-awaited end of the war that had brought the ordeal of Japanese American concentration camps. In this light, the bomb meant relief, albeit a highly undesirable one. Just as the former detainees were encouraged to "readjust" to America's mainstream society after the war, Japanese American hibakusha were made to feel that the bomb was not something to be questioned or even recalled.

Hibakusha Speak Out

The thick silence began to break apart in the 1970s when U.S. bomb survivors started to seek recognition by both the American and the Japanese governments. By then, Japanese American hibakusha included not only the U.S.-born citizens, but also the Japanese people who had come to America in the 1950s and 1960s. Many of these immigrants gained U.S. citizenship, while others became non-citizen residents. Thus, it was crucial for Japanese Americans to define survivorhood broadly in relationship to both countries. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, U.S. survivors campaigned for legislation that aimed to establish medical facilities and services specializing in radiation illness funded either by the federal or state governments in the United States. They also advocated successfully for a system of biannual medical checkups conducted on the U.S. West Coast by Hiroshima and Nagasaki doctors familiar with medical conditions common among survivors.

Such broad activism was rooted in U.S. survivors' ability to come together in spite of their diverse backgrounds and the passage of time. Indeed, U.S. survivors' activism became possible because of the younger, third-generation Asian Americans' interest in the older generations' experiences as racial minorities in the United States. Not only did the younger Asian Americans support legal and legislative aspects of hibakusha' s activism, they also implemented the "Personal History Project" in 1988 which, by conducting oral history interviews with U.S. survivors in the San Francisco Bay Area, helped to bring them out of silence. Part of the rise of interracial and interethnic coalitions in the Asian American civil rights movement that gained momentum in the late 1960s and early 1970s, third-generation Asian Americans also helped expand support for U.S. survivors from African Americans and Latino Americans. Politicians of color such as California's Mervyn M. Dymally, Edward Roybal, Bill Greene, and Tom Bradley came out in support of the medical bills for hibakusha . Although their accomplishments were limited, particularly by the U.S. government's position that it does not pay for the consequences of "legitimate" wartime actions, U.S. survivors in the 1970s and 1980s at least began to speak out and assert their rights as Americans.

Today, U.S. hibakusha receive support from the Japanese government, including not only the biannual medical checkups but also a range of monetary allowances. They do not receive any recognition from their own government, in contrast to the former detainees of incarceration camps who received a formal apology and reparation payments from the U.S. government by the early 1990s. This absence of recognition is in sharp contrast, too, to the compensation given to other U.S. citizens victimized by radiation. With the passage of the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act in 1990, for example, U.S. veterans who had been at nuclear test sites, as well as Native Americans irradiated in uranium mines, became eligible for disability compensation. In this way and others, U.S. hibakusha' s history urges us to consider the legacy of the Good War as it relates to Japanese American history from the perspective of still under-recognized, minority citizens within a minority group.

For More Information

Hein, Laura, and Mark Selden, eds. Living with the Bomb: American and Japanese Cultural Conflicts in the Nuclear Age . Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 1997.

Sodei, Rinjiro. Were We the Enemy?: American Survivors of Hiroshima . Ed. John Junkerman. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1998.

Oral histories of U.S. survivors. Regional Oral History Office, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, CA.

Oral histories of North and South American survivors. Robert Vincent Voice Library, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI.

Committee of A-bomb Survivors in United States of America papers, 1971–75. California State Archives, Sacramento, CA.

Footnotes

- ↑ U.S. survivors' memories cited here were related to the author in a series of interviews. These interviews were conducted between 2010 and 2014, and their records are in the process of being donated to the Robert Vincent Voice Library of Michigan State University in East Lansing, MI.

Last updated July 1, 2014, 9:20 p.m..

Media

Media