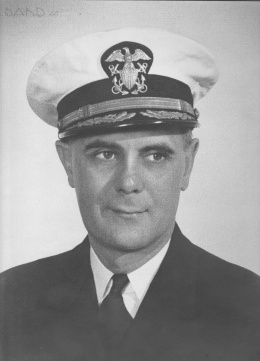

Kenneth Ringle

| Name | Kenneth Ringle |

|---|---|

| Born | September 30 1900 |

| Died | March 23 1963 |

| Birth Location | Hutchinson, KS |

Kenneth Ringle (1900–63) was an Office of Naval Intelligence officer whose prewar investigation of the Japanese American community led him to conclude that Japanese Americans did not pose a security risk as a group and to oppose their mass removal and incarceration. He went on to work for the War Relocation Authority and authored a report on Japanese Americans that was later published anonymously in Harper's magazine in October of 1942.

Before World War II

Kenneth Duval Ringle was born in Hutchinson, Kansas, on September 30, 1900. After graduating from Westport High School in Kansas City, he entered the U.S. Naval Academy, graduating in 1923. Over the next five years, he served tours of duty on the USS Mississippi and the USS Isherwood.

From 1928 to 1931, he served as a Naval Attaché at the U.S. embassy in Tokyo, where he studied the Japanese language and culture intensively, becoming one of the few in the navy to have such skills. After his stint in Japan, he married Margaret Johnston Avery in 1932, then went on to serve as an assistant gunnery officer on the USS Chester from 1932 to 1935. From July of 1936 to July of 1937, he served as an assistant district intelligence officer for the Fourteenth Naval District in Honolulu, Hawai'i, where he no doubt gained greater familiarity with the Japanese American community. He subsequently served as the communications officer on the USS Ranger from 1937 to 1940.

Intelligence Work and the War

Beginning in July 1940, he served as the assistant district intelligence officer for the Eleventh Naval District in Los Angeles. With his knowledge of Japanese language and culture, he was assigned to assess Japanese American loyalty on the West Coast and to engage in counterespionage efforts, tasks he approached with gusto. He built a network of informants within the Japanese American community, particularly among members of the Japanese American Citizens League , whose members were flattered that a military official such as Ringle sought them out. He regularly attended JACL Southern District meetings and hosted a dinner for Southern California JACL chapters in March of 1941. [1] He also interviewed a range of others with knowledge about Japanese Americans and also met with presidential investigator Curtis Munson in the summer of 1941, serving as a key informant and influence on Munson's subsequent report .

In June of 1941, Ringle led a late-night break in to the Japanese consulate in Los Angeles. This raid was accomplished with the cooperation of local police and the FBI and even included a safe cracker that they had pulled out of prison to assist on the job. Information gleaned from the raid included lists of members of a Japanese spy ring that led to the subsequent arrest of Itaru Tachibana. (See Tachibana Case .) These lists served as a key source for the compiling of ABC Lists of those to be arrested in the event of war with Japan.

Based on information from the various sources noted above, Ringle submitted a report in January 1942 that vouched for Japanese American loyalty and argued against mass exclusion. He felt that the vast majority of Japanese Americans were at least "passively loyal" and that any potential saboteurs or enemy agents could be individually identified and imprisoned, as in fact most already had been by that time. He identified Kibei as "those persons most dangerous to the peace and security of the United States," but argued that other Nisei were regarded by Japanese agents as "cultural traitors" who could not be trusted and who thus posed no security threat. [2]

Though his views seemed to be shared by the Office of Naval Intelligence, the navy opted not to challenge the army's actions, and so his report and recommendations were largely ignored. In collaboration with Munson and John Franklin Carter (a close associate of President Roosevelt who had hired Munson), Ringle later proposed a plan whereby Nisei—presumably JACL leaders—be entrusted with supervision of the Issei and their property as an alternative to mass removal. Though tacitly supported by the president, General John DeWitt , head of the Western Defense Command , refused to meet with them. [3]

With mass incarceration a reality, his son Ken Ringle described him at this time as "drained, depressed and feeling somehow an inadvertent accomplice to the betrayal of America's Japanese," in a Washington Post piece. [4] At the request of War Relocation Authority director, Milton Eisenhower , Ringle worked briefly for the WRA in May and June of 1942, expanding his January report to 57 pages, and recommended that Kibei and some Issei be separated out of the camp population, with the rest to be gradually resettled. This report was later published anonymously in Harper's magazine October 1942 issue under the title "The Japanese in America—The Problem and the Solution" by "An Intelligence Officer."

Subsequent Career

For the rest of the war, Ringle saw combat duty on board the USS Honolulu, then as commanding officer of the USS Wasatch from January 1945. He won a Legion of Merit for his performance in the Battle of Leyte Gulf. However, he believed that his intelligence work ended up harming his subsequent career, both because much of that work remained secret and because it took him away from his core naval career. After the war, he commanded a division of transport ships in China. He retired from the navy in 1953, being promoted from captain to rear admiral upon his retirement. He died of a heart attack on March 23, 1963 in Louisiana. [5]

For More Information

Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians . Foreword by Tetsuden Kashima. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997.

Lim, Deborah K. The Lim Report: A Research Report on Japanese Americans in American Concentration Camps during World War II . 1990. http://www.resisters.com .

Ringle, Ken. "What Did You Do Before the War, Dad?" Washington Post Magazine , Dec. 6, 1981: 54–62.

Robinson, Greg. By Order of the President: FDR and the Internment of Japanese Americans Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001.

———. A Tragedy of Democracy: Japanese Confinement in North America . New York: Columbia University Press, 2009.

Footnotes

- ↑ Deborah K. Lim, The Lim Report , (1990), part I, section A-3 and A-4.

- ↑ Brian Masaru Hayashi, Democratizing the Enemy: The Japanese American Internment (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University, 2004), 34; Greg Robinson, A Tragedy of Democracy: Japanese Confinement in North America (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009), 55.

- ↑ Robinson, Tragedy of Democracy , 63, 68.

- ↑ Ken Ringle, "What Did You Do Before the War, Dad?" Washington Post Magazine , Dec. 6, 1981, 61.

- ↑ Additional biographical information comes from a chronology provided to the author by Andrew Ringle.

Last updated Jan. 23, 2024, 10:42 p.m..

Media

Media