Kooskia (detention facility)

| US Gov Name | Kooskia Internment Camp |

|---|---|

| Facility Type | Department of Justice Internment Camp |

| Administrative Agency | U.S. Department of Justice |

| Location | Kooskia, Idaho (46.1333 lat, -115.5833 lng) |

| Date Opened | May 1943 |

| Date Closed | May 1945 |

| Population Description | Held Japanese immigrants from the U.S. and Latin America, as well as as well as one Italian national and one German national, at different times. |

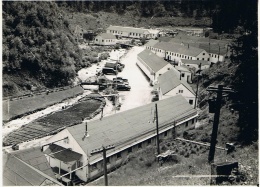

| General Description | Located in Clearwater National Forest in North Central Idaho, 40 miles east of the town of Kooskia. Set in a remote, heavily wooded area, the facility had been a highway construction camp sited on an old Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp. |

| Peak Population | |

| National Park Service Info | |

| Other Info | |

A Justice Department internment camp in north central Idaho. The Kooskia (KOOS-key) Internment Camp, about 30 miles east of the town of Kooskia, operated between May 1943 and May 1945. Over time, it held a total of some 265 so-called "enemy aliens" of Japanese ancestry.

Before the War

Prior to the Kooskia camp's establishment, the location housed a Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp from mid-June to mid-October 1933. Beginning in late August 1935, the site became a 200-man federal prison camp for inmates convicted of crimes against U.S. laws, such as mail robbery and selling liquor to Indians. The prisoners, all trusties, helped construct the Lewis-Clark Highway, now U.S. Highway 12, between Lewiston, Idaho, and Missoula, Montana.

Wartime Internment

By early 1943, expenses related to U.S. involvement in World War II resulted in lessened appropriations for the prison system, so the federal prison camp closed. Because the route had been declared a First Priority Military Highway, the camp reopened almost immediately as the Kooskia Internment Camp, today an obscure and virtually forgotten World War II detention facility that the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) operated for the Justice Department between May 1943 and May 1945. Located in a remote area of north central Idaho, where Canyon Creek enters the Lochsa River, it was unrelated to the War Relocation Authority 's Minidoka concentration camp in southern Idaho, now the Minidoka National Historic Site, some 400 miles away.

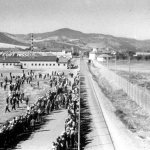

The Kooskia Internment Camp is unique not only because it was the only work camp in the U.S. for Japanese internees, but also because the Kooskia internees achieved a remarkable amount of control over their own lives, first by volunteering to go there and then by petitioning to improve their living and working conditions. The first group of 104 volunteers were from the Santa Fe , New Mexico, Internment Camp. Others came from Fort Meade, Maryland; Camp Livingston, Louisiana; and Fort Missoula, Montana.

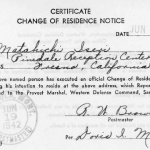

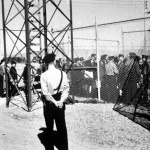

Over time, the Kooskia camp's Japanese internees eventually numbered about 265 men, [1] with a maximum that was under 200 at any given time. Their ages ranged from the low-twenties to the mid-sixties. They came from both coasts and from a variety of states, from the then-territories of Alaska and Hawai'i, and from Mexico; some were even kidnapped from Panama and Peru. Depending upon their origins and education, they spoke Japanese, English, and/or Spanish. All were previously detained in other INS camps for "enemy aliens." As internee road workers in Idaho, they received wages of $55 to $65 per month. Despite their diverse backgrounds, different languages, and varied occupations, wartime anti-Japanese hysteria had brought them together. At the Kooskia Internment Camp they formed into a cohesive unit, defying racist stereotyping to win praise and admiration for their work ethic and for their successful achievements.

The camp had about 25 Caucasian employees, including several women. In mid-1944, when Fort Missoula Internment Camp closed, a Japanese American man joined the Kooskia camp staff as interpreter, translator, and censor. Two successive internee doctors, an Italian and a German, provided medical services to the internees and employees.

Although some of the internees held camp jobs, most were construction workers for the road that paralleled the wild and scenic Lochsa River. Housing the Kooskia Internment Camp in this pristine wilderness presented a paradox between the spectacular beauty of the surroundings and the injustice of the Japanese aliens' internment. Tommy Yoshito Kadotani, a landscape gardener from California, called it "…a paradise in mountains!" saying, "It reminds me so much of Yosemite National Park." [2] Since many of the Kooskia internees came there from the Santa Fe Internment Camp, in the New Mexico desert, the Kooskia camp site must have seemed like "paradise" in comparison. However, by early July 1943, the internees realized, instead, that they were actually "shut off from the rest of world and [were] living in the Noman [no man's] land," [3] and that conditions at the Kooskia Internment Camp were not what they had been promised.

The men's unhappiness stemmed from an awareness of their rights under the terms of the 1929 Geneva Convention as implemented by an INS directive. [4] Since censorship prevented the internees' dissatisfaction from reaching the outside world, they soon prepared a lengthy petition detailing their complaints and submitted it to Bert Fraser, the officer in charge at the Fort Missoula Internment Camp in Montana. [5]

Because the volunteer internees were crucial to the success of the road-building project, the INS moved quickly to address their concerns, and the next few months saw many welcome changes at the Kooskia camp. These involved increased attention to medical and dental care, improvements in procedures and recreation, and changes in administrative staffing. Most significant was the resignation of the first Kooskia camp superintendent; he was notorious for treating the detainees as criminals rather than as internees.

Of all the aliens detained by the INS who were subject to the humane provisions of the Geneva Convention, the Kooskia internees were one of only two groups to use that document to its greatest effect. Earlier, in June 1942, internees at the Lordsburg, New Mexico, Internment Camp called a strike to protest being forced to work outside the camp area, which the Geneva Convention prohibited. [6] Since some of the Kooskia internees had previously been at Lordsburg, they may have brought that knowledge with them.

In mid-November 1943, morale was further enhanced when Merrill H. Scott became the new superintendent at the Kooskia camp. One official visitor commented, "…Mr. Scott…seems to know every internee by name; has direct and personal contacts with all of them; [and] they hold him in highest respect and esteem…." [7] Scott's sympathy for the internees' plight, combined with his obligations for their care as detailed in INS regulations based on Geneva Convention requirements, ensured that the Kooskia internees would finally be treated in a dignified and respectful manner. A few difficulties still remained to be corrected, but with the major irritant in their lives removed, the men's patience and cooperative attitude allowed time for other problems to be addressed and solved.

The Kooskia camp closed in May 1945, mainly because internee numbers had dwindled, due to paroles, and because it was difficult to obtain spare parts for the equipment. [8] On May 2, 1945, the remaining Kooskia internees, numbering just 104 men, all departed for the Santa Fe Internment Camp.

After the War/Current Status

During the next few years, the camp's buildings were gradually removed and the Lewis-Clark Highway was finally completed. Soon there was little to be seen at the former Kooskia Internment Camp, and it risked being forgotten. The Clearwater National Forest (CNF), a unit of the U.S. Forest Service (USFS), owns the property; in the 1970s, the USFS directed the CNF and other forests to research archaeological sites on their lands. [9] As part of this work, in 1978 Forest Service archaeologists collected ceramic artifacts from the surface, including, but not specifically mentioned in the report, the base of a Japanese rice bowl marked "MADE IN JAPAN." [10] Today, except for the handball court's concrete slab surface, and level areas that held the former buildings and baseball diamond, almost nothing remains to remind us of the Kooskia Internment Camp's contribution to both American and Japanese American history.

The Forest Service also conducted interviews with now-deceased, former employees, [11] and in 1982 the CNF recorded the internment camp phase in greater detail with more interviews, documents, and photographs. [12] Because the interviews were only with Caucasian employees, not with Japanese internees, the 1990s saw efforts to obtain the Japanese internees' perspectives on their experience. Funding from the Civil Liberties Public Education Fund (CLPEF), the Idaho Humanities Council, and the California Civil Liberties Public Education Program (CCLPEP) enabled documentary research to be accomplished in the National Archives in Washington, DC, and elsewhere. Records from the INS, the USFS, and the U.S. Border Patrol included maps; censored and uncensored letters; individual and group photographs; and snapshots depicting camp buildings, working conditions, and leisure activities. [13] Interviews with two surviving internees gave life and perspective to the abundant archival documents.

In December 2006, to preserve and interpret U.S. sites where Japanese Americans were detained during World War II, the U.S. Congress established the Japanese American Confinement Sites grant program (Public Law 109-441). [14] For fiscal year 2009, the National Park Service (NPS) awarded grants to qualifying entities, one of which was the Kooskia Internment Camp. The University of Idaho received nearly $16,500 for archaeological testing there in the summer of 2010, with work to continue in the summer of 2013, under another NPS grant. [15]

The ultimate significance of the Kooskia Internment Camp, and what differentiates it from the other internment or concentration camps, lies in the internees' awareness and exploitation of the rights and privileges guaranteed to them by the Geneva Convention. The Kooskia internees' knowledge of this document and its provisions empowered them in establishing a good working relationship between themselves and the Kooskia camp administration. Since the road building project could not function without the internees, their refusal to accept substandard living and working conditions was crucial in compelling the INS to agree to their demands.

For More Information

Asian American Comparative Collection: The Kooskia Internment Camp Project. http://www.uiweb.uidaho.edu/aacc/KOOSKIA.HTM .

The Kooskia Internment Camp Archaeological Project. http://www.uidaho.edu/class/kicap/ .

University of Idaho Library Digital Collections: Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook. http://contentdm.lib.uidaho.edu/cdm4/browse.php?CISOROOT=/spec_kic .

Wegars, Priscilla. Imprisoned in Paradise: Japanese Internee Road Workers at the World War II Kooskia Internment Camp . Moscow, ID: Asian American Comparative Collection, 2010.

---. As Rugged as the Terrain: CCC "Boys," Federal Convicts, and World War II Alien Internees Wrestle with a Mountain Wilderness. Foreword by Dick Hendricks. Caldwell and Moscow, ID: Caxton Press, in association with the Asian American Comparative Collection, University of Idaho, 2013. [Includes three chapters on the Kooskia camp.]

Footnotes

- ↑ The exact number is not certain because available lists are incomplete. Several men suspected of being confined at the Kooskia Internment Camp could not be located in records at the National Archives in Washington, DC, or in College Park, MD.

- ↑ Yoshito Kadotani, Kooskia Internment Camp, to Sanzo Aso, Santa Fe Internment Camp, May 28, 1943; Entry 291, Records of Enemy Alien Internment Facilities, World War II, Fort Missoula, MT, General Files, 1942-1949, 1000/Kooskia (2) [Box 4, second white folder], Record Group 85, Records Related to the Detention and Internment of Enemy Aliens during World War II, Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.; Paul S. Kashino, official censor, translator, and interpreter, Fort Missoula Internment Camp, interpreted, censored, copied, excerpted, and/or translated the original communication [henceforth E291, RG85, NARA I, PSK].

- ↑ [Kooskia internees] to Bert H. Fraser, Officer in Charge, Fort Missoula Internment Camp, July 7, 1943, 1; E291, RG85, NARA I, PSK. Document courtesy Louis Fiset.

- ↑ The Geneva Convention is a 1929 international agreement specifying conditions for holding prisoners of war (POWs); it was later extended to internees. The related INS directive is Lemuel B. Schofield, Special Assistant to the Attorney General, U.S. Department of Justice, Immigration and Naturalization Service, Philadelphia, PA, "Instruction No. 58, Instructions Concerning the Treatment of Alien Enemy Detainees," April 28, 1942, 9-10; E291, 1022/X, [Geneva Convention, Box 24], RG85, NARA I, also available at http://home.comcast.net/~eo9066/1942/42-04/IA119.html (accessed December 27, 2011).

- ↑ [Kooskia internees] to Bert H. Fraser.

- ↑ Yasutaro Soga, Life Behind Barbed Wire: The World War II Internment Memoirs of a Hawai'i Issei (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i, 2008), 76. Tetsuden Kashima, "Introduction," in Soga, Life Behind Barbed Wire , 8, adds, "their protest eventually led to the transfer of this particular camp commander out of the Lordsburg center," which also happened at the Kooskia camp.

- ↑ W. F. Kelly, Assistant Commissioner for Alien Control, U.S. Department of Justice, Immigration and Naturalization Service, Philadelphia, PA [henceforth WFK], to Joseph Savoretti, Deputy Commissioner/Assistant Commissioner for Adjudication, U.S. Department of Justice, Immigration and Naturalization Service, Washington, D.C., Mr. Mangione, Miss Hersey, September 14, 1944; together with Charles E. Eberhardt, Special War Problems Division, Department of State, Washington, D.C., to WFK, September 8, 1944, 4; both Accession Number 85-58A734, File Number 56125/157, Box 2436 [INS Records/Inspection Reports Re: Visits to Detention Facilities], RG85, NARA I.

- ↑ "News of the Month: Kooskia Internment Camp Is Abandoned by Service," Monthly Review , 2:2 (May 1945), 148; Hugh Carter et. al., "Administrative History of the Immigration and Naturalization Service during World War II," typescript (General Research Unit, Office of Research and Educational Services, INS, U.S. Department of Justice, INS Library, Washington, D.C., 1946), 305.

- ↑ E.g., H[oward] Watts and Fred Kuester, "Cultural Site Record [for] 10-IH-870," Clearwater National Forest Supervisor's Office, Orofino, ID [henceforth CNFSO], 1979. The site number, 10-IH-870, is part of a system devised by the Smithsonian Institution for recording archaeological sites. In an alphabetical list of states, Idaho is tenth; IH stands for Idaho County, and the federal prison camp/Kooskia Internment Camp site is the 870th archaeological site recorded in Idaho County.

- ↑ Watts and Kuester, "Cultural Site Record [for] 10-IH-870," 2, and "Ceramics from the Kooskia Internment Camp, 10-IH-870," Asian American Comparative Collection Newsletter 20:2 (June 2003), 3. In the early 1990s, while visiting the site, the son of a former internment camp guard found the base of a Japanese teacup with an identical mark, Micheal Moshier, e-mail message to author, March 27, 2005.

- ↑ E.g., Alfred Keehr and Dorothy Keehr, interview by Ramona Alam Parry, July 12, 1979, transcript, CNFSO.

- ↑ E.g., Amelia Jacks and Edwin Jacks, interview by Dennis Griffith, March 25, 1982, transcript, and Dennis Griffith, Reply to: 2360 Special Interest Area. Subject: History of Japanese Internment Period: Canyon Creek Prison Camp Site. Lochsa District, Kooskia Ranger Station, Kooskia, ID [henceforth LDKRS], [1982]. These materials are now housed at the LDKRS and at the CNFSO.

- ↑ Materials that were particularly helpful included a photograph album owned by former Kooskia camp guard E. D. Mosier; individual internees' Closed Legal Case Files at the National Archives; and a diary, in English, by Reverend Hozen Seki, a Buddhist minister from New York City. Thanks to Micheal Moshier for calling the album to my attention. Called a "scrapbook" because it includes two drawings in addition to the photographs, it is now housed in the University of Idaho Library Special Collections, with the call number PG 103. The photographer, who is unknown, could have been an employee or even an internee; two internees were former photographers. Thanks to Hoshin Seki for providing a copy of his father's diary, now in the Asian American Comparative Collection, University of Idaho, Moscow. Much additional information came from local newspapers. While they were very useful for depicting life at the Kooskia camp, they unfortunately contain frequent instances of offensive, anti-Japanese terminology.

- ↑ National Park Service, Japanese American Confinement Sites Preservation , "Public Law 109-441-Dec. 21, 2006, Preservation of Japanese American Confinement Sites," accessed December 7, 2011 at http://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/hps/HPG/JACS/downloads/Law.pdf .

- ↑ Kara Miyagishima, e-mail message to author, July 24, 2009; Kathy Hedberg, "UI Prof Goes in Search of the Past," Lewiston (ID) Tribune , August 10, 2009, 5A. Assistant professor Stacey Camp of the University of Idaho's Department of Sociology/Anthropology directed the 2010 project and will continue her archaeological research there in 2013.

Last updated June 16, 2020, 3:33 p.m..

Media

Media