Leland Ford

| Name | Leland Merritt Ford |

|---|---|

| Born | March 8 1893 |

| Died | November 27 1965 |

| Birth Location | Eureka, NV |

Leland Merritt Ford (1893–1965), United States House of Representatives member from California, who became the first congressman to publicly advocate for the forced removal and placement of people of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast into concentration camps following Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor.

Early Life

Ford was born in Eureka, Nevada, to James Green Ford and Anna L. Ficklin. He attended a number of colleges, including the University of Arizona at Tucson, Virginia Polytechnic Institute, the Sheldon Science of Business in Chicago and the University of California, Los Angeles. From 1909 to 1910, he was a surveyor for the Southern Sierras Power Company, and then found employment in the California and New York offices of the Southern Pacific Railroad.

He married Elizabeth Beryl Seger in 1914, and the couple lived in Los Angeles for a year before moving to Virginia, where Ford tried his hands at farming and livestock breeding. In 1919, he moved to Santa Monica, California, and became involved with the real estate business. He served on the Santa Monica Planning Commission from 1923 to 1927 but it was his election to the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors in 1936 that launched his stint in public office. In 1939, Ford was elected as the Republican Congressman from Santa Monica, and played a significant role in Los Angeles politics from the late 1930s to early 1940s. Because Ford was anti-labor and anti-New Deal, he received the support of the Los Angeles Times , which opposed unionization of its workers

World War II Years

When Congressman John Rankin of Mississippi called for the deportation of "every Jap who claims, or has claimed, Japanese citizenship, or sympathizes with Japan in this war, Ford responded to Rankin by defending Japanese American loyalty to the United States." [1] Ford, however, reversed his position after he began getting anti-Japanese letters and telegrams from California residents, including from Mexican American movie star Leo Carillo. Ford started writing letters as early as January 6 to various officials, placing him as the first congressman to try to exert pressure on administration officials. In his early January 1942 correspondences, Ford argued that American-born Japanese were being given a chance to show their patriotism if they willingly entered a concentration camp:

That all Japanese, whether citizens or not, be placed in inland concentration camps. As justification for this, I submit that if an American born Japanese, who is a citizen, is really patriotic and wishes to make his contribution to the safety and welfare of this country, right here, is his opportunity to do so, namely, that by permitting himself to be placed in a concentration camp, he would be making his sacrifice and he should be willing to do it if he is patriotic and is working for us. As against his sacrifice, millions of other native born citizens are willing to lay down their lives, which is a far greater sacrifice, of course, than being placed in a concentration camp. [2]

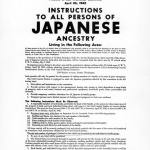

By late January 1942, Ford's letters to Attorney General Francis Biddle went one step further and said all people of Japanese ancestry should be placed into concentration camps, whether they went willingly or not, and that only disloyal Japanese would oppose their own incarceration.

On January 20, 1942, Ford became the first congressman to call for the mass removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast on the House floor, while alleging that American-born Japanese were broadcasting propaganda from Japan. [3] Starting in January 1942, the mainstream media began writing stories of having Japanese Americans moved inland to raise food for the war effort, but Ford became the first person to call for an outright imprisonment of Japanese Americans in concentration camps, making such statements in the Los Angeles Examiner on Jan. 20, 1942 and the Los Angeles Times and San Francisco Examiner on Jan. 22, 1942. [4]

Leadership of Coalition of West Coast Congressmen

The war also gave rise to what was referred to as the ad hoc bipartisan caucus of representatives of the western region, which included congressional delegations from California, Washington and Oregon. By February 1942, this organization was demanding the mass removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast. Voices for moderation came from California Senator Sheridan Downey, California Congressmen Bertrand Gearhart and H. Jerry Voorhis, and Washington Congressman John Coffee. However, the West Coast Congressional group meetings became tense as extremists allowed no room for compromise.

By February 1942, the West Coast congressional delegation members were calling Justice Department official Edward Ennis daily; sending out press releases to the public demanding the immediate removal of the Japanese Americans from the West Coast; and denouncing the DOJ for inaction, even threatening an investigation.

In recalling a February 1942 conversation with Biddle, Ford told Morton Grodzins:

I phoned the Attorney General's office and told them to stop fucking around. I gave them twenty four hours notice that unless they would issue a mass evacuation notice I would drag the whole matter out on the floor of the House and of the Senate and give the bastards everything we could with both barrels. I told them they had given us the run around long enough... and that if they would not take immediate action, we would clean the god damned office out in one sweep. I cussed at the Attorney General and his staff himself just like I'm cussing to you now and he knew damn well I meant business. [5]

The issue of forcibly removing Japanese Americans from the West Coast came up for debate in Congress on Feb. 18. At that time, California Congressman John Costello inserted into the Congressional Record a Feb. 5 speech by Los Angeles Mayor Fletcher Bowron , calling for the immediate removal of the Japanese Americans from the West Coast and putting them to work for the war effort. The following day, on Feb. 19, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 , allowing military authorities to remove anyone deemed a security threat without a hearing.

After EO 9066

Once Ford discovered that the Owens Valley in California would be one of the sites for a camp, he unsuccessfully protested to the Justice Department. At one point, Ford even visited the Manzanar camp, observing the hastily built nature of the barracks.

In August 1942, the Daily News reported that Ford was part of the Citizens Committee to Keep America Out of War's executive committee. A federal grand jury had investigated this organization, and although no criminal charges had been filed, the Daily News article noted that "the jurors did return indictments against the alleged Nazi agents and seditionists who are charged with using Ford, [U.S. Rep. Hamilton] Fish [of New York] and other congressional obstructionists of the administration's war and defense policies." The newspaper article described the committee as a "Nazi stooge group," and the report affected Ford's reelection campaign. He lost his seat in 1942 to Democrat Will Rogers, Jr. [6]

When a riot broke out at the Manzanar War Relocation Authority camp in December 1942, Ford told the press that he blamed the lenient policies of the WRA for the unrest. Ford described WRA policies as "social experiments," which allowed Japanese Americans to move about the country too freely. He called for stricter control of the Japanese American population.

Once Ford's congressional term ended in January 1943, he returned to private life as a real estate businessman. He died on November 27, 1965.

For More Information

Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. Personal Justice Denied . 1982. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997.

Daniels, Roger. Concentration Camps North America: Japanese in the United States and Canada During World War II , revised edition. Malabar, Fla.: Robert E. Krieger Publishing Company, Inc., 1981.

Grodzins, Morton. Americans Betrayed: Politics and the Japanese Evacuation . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1949. Midway Reprint, 1974.

Leonard, Kevin Allen. The Battle for Los Angeles: Racial Ideology and World War II . Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2006.

tenBroek, Jacobus, Edward N. Barnhart, and Floyd W. Matson. Prejudice, War and the Constitution . Berkeley: University of California Press, 1954, fifth printing, 1975.

Footnotes

- ↑ Roger Daniels, Concentration Camps North America: Japanese in the United States and Canada During World War II , revised edition (Malabar, Fla.: Robert E. Krieger Publishing Company, Inc., 1981), 43.

- ↑ Ford to FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover and Secretary of Navy Frank Knox, January 6, 1942, cited in Morton Grodzins, Americans Betrayed: Politics and the Japanese Evacuation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1949), 65. He sent copies of the same letter to others, see Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, Personal Justice Denied (1982. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997), 70.

- ↑ Congressional Record, 502, cited in Grodzins, Americans Betrayed , 66.

- ↑ Grodzins, Americans Betrayed , 394.

- ↑ Report No. 6, Grodzins in Washington, Sept. 26, 1942, Bancroft Library, cited in Personal Justice Denied , 84.

- ↑ Kevin Allen Leonard, The Battle for Los Angeles: Racial Ideology and World War II (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2006), 67.

Last updated Oct. 8, 2020, 2:58 p.m..