Old Raton (detention facility)

| US Gov Name | Old Raton Ranch Internment Camp |

|---|---|

| Facility Type | Department of Justice Internment Camp |

| Administrative Agency | U.S. Department of Justice |

| Location | Lincoln, New Mexico (33.4833 lat, -105.3833 lng) |

| Date Opened | January 23, 1942 |

| Date Closed | December 18, 1942 |

| Population Description | The entire Japanese American population of Clovis, New Mexico, a total of thirty-two people. |

| General Description | An abandoned Civilian Conservation Corps camp located 13 miles east of Fort Stanton internment camp in the Lincoln National Forest in southern New Mexico; also known as Baca Ranch Camp |

| Peak Population | 32 (1942-01-23) |

| Exit Destination | Poston, Gila River and Topaz WRA incarceration camps |

| National Park Service Info | |

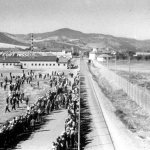

INS-run facility specifically set up at an old Civilian Conservation Corps camp in January 1942 to intern ten Japanese American railroad workers removed from Clovis, New Mexico, and their families—a total of thirty-two people—for almost a year. Isolated and with the children largely deprived of education, the group was finally transferred to WRA camps in late 1942. None of the families returned to New Mexico after the war.

Prior to the war, the entire Nikkei community in Clovis—as well as much of the rest of the town—was associated with the Santa Fe Railroad. Located just ten miles from the Texas border, the entire economy of Clovis was built around its status as a railroad junction that served the many freight trains that passed through. The ten Nikkei men who worked for the Santa Fe in Clovis had all been there for twenty years or more, many holding senior machinist positions. Though the area was rife with racism against all ethnic minorities including the Nikkei, the small group peacefully co-existed with the larger community, and the children attended local schools. Most of the Nikkei lived in a company-owned compound that included one-story buildings used for housing along with gardens, a bathhouse, koi pond, and Buddhist altar. The townspeople called it "Jap Town," "Jap Camp," or "Jap Quarters." [1]

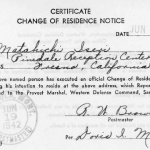

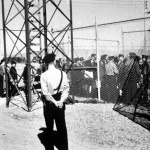

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Clovis Nikkei found themselves in limbo. Santa Fe Railroad officials ordered the Nikkei to stop working and to remain in their quarters due to local antagonism and threats made against them. At the same time, the local U.S. attorney decreed that local authorities could not detain them, that only the Justice Department could do so. Finally, after more than a month, Border Patrol officers arrived on January 19, and determined to remove the Nikkei population. Late on the evening of January 23, the group left by car for an unknown destination. The group of thirty-two consisted of fifteen Issei and seventeen Nisei. Two families—the Ebiharas and the Kimuras—each consisted of an Issei husband and wife and seven children and thus made up more than half of the group. There were three other married couples with a total of three children, and five additional men, two of whom were single, one widowed, and two with wives in Japan. [2]

Taken first to the Fort Stanton camp, they moved on to a separate CCC camp called the Baca Ranch Camp about thirteen miles east of Stanton and some 175 miles from Clovis. The fourteen acre site included nine buildings, including various cabins and barracks along with a meeting hall and dining room and kitchen. The internees had to clean and repair their own quarters, including patching walls and exterminating beg bugs. They also cooked their own meals on wood burning stoves in their quarters, with provided foodstuffs. There was no running water in the barracks, but an adjacent latrine area had flush toilets, showers, and laundry facilities. Due to its remote location at the end of twelve miles of unpaved roads, no fences were deemed necessary. The site was picturesque, with the Capitan Mountains visible to the north, and the older children enjoyed exploring the mountain trails. But the isolation and uncertainty took its toll. Ammon M. Tenney, the officer-in-charge, wrote that the experience "was conducive to despondency and suicide." The twelve children were first sent to school in the town of Capitan, ten miles away, soon after their arrival. But local hostility forced them to be withdrawn by February 9. Efforts to secure a teacher for the camp failed, as did efforts to compel local schools to take them. Amy Ebihara, who had been a high school junior, was compelled to teach the other children with books provided by her former principal. [3]

While one of the single men was able to secure parole in order to leave for work on a Utah farm in April, the rest of the group was stuck at Old Raton Ranch for nearly a year. The INS and War Relocation Authority were finally able to reach an agreement to have the internees taken to WRA camps late in 1942. Most of the Nikkei had family members at one of the WRA camps whom they were allowed to join. The nine Kimuras left for Poston on November 23, while the Ebiharas and one other went to Topaz on December 15. All the rest went to Gila River on December 12. Old Raton Ranch was empty by December 18. Though the ten Santa Fe Railroad workers all wanted to return to their jobs, none ever did, and most ended up settling in other parts of the U.S. after released from the WRA camps. [4]

In 2013, Adrian Chavez learned of the history of the Clovis Nikkei in a college class and was inspired to track town Roy Ebihara to lobby local officials to recognize them. As a result, the 2014 Pioneer Days Parade in Clovis was dedicated to the Nikkei removed from Clovis. Ebihara, Fred Kimura and Lillie Kumura Kiyokawa returned with relatives and served as honorary grand marshals in the parade and received keys to the city. [5]

The site of the Old Raton Ranch Camp is part of the Baca Campground in Lincoln National Forest, where there are remains of foundations and Japanese gardens. [6]

For More Information

Culley, John J. "World War II and a Western Town: The Internment of Japanese Railroad Workers of Clovis, New Mexico." Western Historical Quarterly 13.1 (Jan. 1982): 43-61.

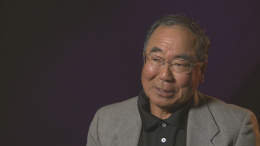

Roy Ebihara interviews , 2008 and 2012. Densho Digital Repository.

Nicholas, Kellie, and Yancy Bush. "Section Three: The 2014 Pioneer Days Celebration in Clovis, New Mexico." In Confinement in the Land of Enchantment . Ed. Sarah R. Payne. Fort Collins, Colo.: Colorado State University, Public Lands History Center, [2017]. 107–09.

Russell, Andy. "Clovis: New Mexico's Peculiar Mass Exclusion." In Confinement in the Land of Enchantment . Ed. Sarah R. Payne. Fort Collins, Colo.: Colorado State University, Public Lands History Center, [2017]. 59–75.

Footnotes

- ↑ Andy Russell, "Clovis: New Mexico's Peculiar Mass Exclusion," in Confinement in the Land of Enchantment , ed. Sarah R. Payne (Fort Collins, Colo.: Colorado State University, Public Lands History Center, [2017]), 59–61; John J. Culley, "World War II and a Western Town: The Internment of Japanese Railroad Workers of Clovis, New Mexico," Western Historical Quarterly 13.1 (Jan. 1982), 46–47.

- ↑ Culley, "World War II and a Western Town," 48–53; Russell, "Clovis: New Mexico's Peculiar Mass Exclusion," 63–65.

- ↑ Russell, "Clovis: New Mexico's Peculiar Mass Exclusion," 67–71; Culley, "World War II and a Western Town," 53–56; Roy Ebihara interview by Andrew Russell, Segments 15 and 16, Roswell, New Mexico, March 7, 2008, New Mexico JACL Collection, Densho Digital Repository, https://ddr.densho.org/media/ddr-densho-1009/ddr-densho-1009-1-transcript-5ad0eceaa8.htm .

- ↑ Culley, "World War II and a Western Town," 57–58; Russell, "Clovis: New Mexico's Peculiar Mass Exclusion, 71.

- ↑ Kellie Nicholas and Yancy Bush, "Section Three: The 2014 Pioneer Days Celebration in Clovis, New Mexico," in Confinement in the Land of Enchantment , ed. Sarah R. Payne (Fort Collins, Colo.: Colorado State University, Public Lands History Center, [2017]), 107–09.

- ↑ Barbara Wyatt, ed., Japanese Americans in World War II: National Historic Landmarks Theme Study (Washington, D.C.: National Historic Landmarks Program, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 2012), 168.

Last updated July 6, 2021, 9:32 p.m..

Media

Media