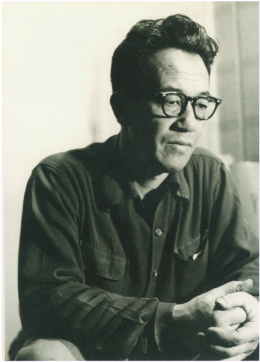

Paul Horiuchi

| Name | Paul C. Horiuchi |

|---|---|

| Born | April 12 1906 |

| Died | September 29 1996 |

| Birth Location | Kawaguchiko, Japan |

| Generational Identifier |

Artist Paul Horiuchi (1906-99) was widely known for his work in torn-paper collage, a method he developed in the late 1950s. Born in Japan, he arrived in the United States as a teenager and worked on the railroad in Wyoming until World War II, when he lost his job and his home. He struggled to find work and housing throughout the war, and afterward, settled in Seattle. Over the next decade his artistic method and style changed from representational oil painting to abstract collage. He achieved national recognition in the 1960s and continued to work into the 1990s.

Early Years

Paul Horiuchi, named Chikamasa at birth, was born in 1906 in Ooishi Village, now Kawaguchiko, in Yamanashi Prefecture. [1] The town lies on the shore of Lake Kawaguchi, one of the five lakes surrounding Mount Fuji, a beautiful but then economically stressed region. He was the second son in a family whose ancestors were landowners; his father was a craftsman and shop owner. Little more than a month after his birth, his father left home for the United States, where he found work on the Union Pacific Railroad in Wyoming. A few years later his mother left Japan to join her husband. Chikamasa and his older brother lived in the home of his aunt and an older cousin, Shigetoshi Horiuchi, until Shigetoshi's father, already in Seattle, called his son to join him. Shigetoshi's family left behind a large collection of Japanese and Western literature, which would form the foundation for the younger Horuichi's lifelong pursuit of reading. Chikamasa and his brother, Toshimasa, then lived with their paternal grandfather, Chobei Horiuchi, a well-educated man and community leader. Chikamasa was fascinated by the itinerant painters who frequented Ooishi to paint Mount Fuji and gained his grandfather's permission to study with the artist Iketani. He studied sumi for two years and watercolor a third year.

Preceded by his brother, Horiuchi, age fourteen, left Japan in 1920 to join his father in Kanda in southwest Wyoming. Within months, claiming to be sixteen, he began working for Union Pacific, the major transcontinental railroad. Only a year after his arrival, however, his father died, and his mother, respecting her husband's wishes, returned to Japan with their three American-born children. Horiuchi and his brother remained in Wyoming. By age seventeen, he advanced to section foreman for the railroad, a position typically held by Japanese immigrants. The company, after witnessing a brutal uprising against its Chinese laborers, had established a policy of hiring workers of different ethnicities and nationalities to ensure that no one group would dominate. Horiuchi lived in a company cabin and was responsible for track maintenance for seven miles on either side.

He also committed himself to painting, and by 1929 was accomplished enough to be the subject of an article in The Salt Lake Tribune . As a railroad employee, he could ride free and took every opportunity to visit his cousin Shigetoshi in Seattle. Shigetoshi's father, the owner of a trading company, had returned to Japan and left a substantial art collection to his son, who continued to build it and became one of Seattle's most prominent collectors of Asian art. Horiuchi used his cousin's address in submitting paintings to the Northwest Annual exhibitions, and in 1930 first had a painting accepted by the exhibition jury. Through Shigetoshi, he became acquainted with Issei painters such as Kenjiro Nomura and Kamekichi Tokita . Through him also, Horiuchi was introduced to Bernadette Suda (1913-2015), a Seattle Nisei . He accepted her faith, Catholicism, and the Christian name Paul, and they were married in 1935. They made their home in the railroad house in Wyoming, where two sons were born, Paul Michio (born 1936) and Jon Yasuo (1938-2008).

Wyoming life offered few artistic contacts until 1938, when Vincent Campanella, a young painter from New York, was assigned to the Works Progress Administration regional art center in nearby Rock Springs. Horiuchi began studying with Campanella, and the two became good friends. Energized by the contact, he exhibited his paintings—expressive landscapes of Wyoming, a Rock Springs street scene, and robustly composed portraits of Bernadette—in regional exhibitions in Oakland and San Francisco as well as Seattle. He would name his youngest son, Vincent Masao (b. 1947) in Campanella's honor, and throughout his life credited Campanella's instruction and support.

Wartime and Resettlement

On February 22, 1942, three days after the signing of Executive Order 9066 authorizing mass removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast, Horiuchi and all other employees of Japanese ancestry were fired by the Union Pacific and given twenty-four hours to vacate company-owned homes. Horiuchi packed the family's belongings into the car, saved a roll of his best paintings, and burned everything that connected him to Japan—family photographs, correspondence, and the large collection of Japanese books that he had assembled by setting money aside each month for many years. After a difficult year in Wyoming, unable to find housing or regular work, he and his family moved to Ogden, Utah, where they lived in a small trailer and he pieced together a series of jobs. In early 1945, they moved to Spokane, Washington, when a family friend offered him an apprenticeship in an auto repair shop that specialized in body work.

After Japan's formal surrender in September 1945, Horiuchi's cousin, Shigetoshi, and a number of family friends who had been incarcerated in War Relocation Authority camps returned to Seattle. Horiuchi and his family moved once more, settling in Seattle in 1946. He opened his own auto body shop and quickly gained a reputation for his ability to match colors.

Artistic Innovation and Recognition

Within a year of his move, a painting by Horiuchi won first prize at the Western Washington State Fair, the same fairground where the Puyallup temporary detention center had confined more than 7,000 Nikkei in 1942. It was the first of frequent exhibitions and awards. Having had a painting first accepted in the juried Northwest Annual in 1930, he exhibited nearly every year from 1947 until the series ended in 1975. He participated in the many kinds of regional exhibitions that flourished after the war, and by 1950 was among the "important artists of the region" invited to present work annually at the Bellevue Arts and Crafts Fair. [2] With his move, Horiuchi also reconnected with prewar artist friends and was instrumental in persuading Nomura to paint again. [3]

An accident in which Horiuchi's arm was severely broken became a turning point in 1950. Unable to return to auto repair work, and encouraged by Shigetoshi and an older friend Tamotsu Takazaki, he opened a small antique shop, built a studio in back, and for the first time focused primarily on painting. Artist Mark Tobey became a frequent visitor and mentor, who encouraged Horiuchi to look to his Japanese heritage. They discussed art and philosophy with Takazaki, a Zen master, and practiced sumi with several Nikkei artists. Influenced by Tobey, Horiuchi turned from oil paint to casein on paper as he explored expressive brushwork in a shift from representation to abstraction. The modernist gallery owner Zoe Dusanne began showing his work in 1952 and in 1957 presented his first solo exhibition, which set a gallery record for sales.

Horiuchi's signature work in collage developed in the late 1950s. Inspired by weathered advertisements peeling from storefronts, he explored the evocative effects of torn paper glued to canvas. He painted the papers he would tear in deep, rich colors and a broad range of sumi blacks. He likened the process of tearing to ceramics, in which the maker surrenders control of the material to nature. His art became one of color, shape, and a refined sensitivity to placement; his compositions ranged from intimate to monumental. His themes were often the natural landscape, and as the successful sales of his work enabled him to travel regularly to Japan, many incorporated references to Japanese culture. In later years he increasingly sought an expression of repose, which he viewed as an antidote to the cacophony of contemporary life. He produced several thousand paintings (as he called the collages) in his lifetime.

Horiuchi's work in collage brought sustained success. The Seattle Art Museum and the Little Rock Fine Arts Museum presented solo exhibitions in 1958. With Dusanne's advocacy, he was featured in Time magazine and Art International , and his work included in Herbert Read's 1959 exhibition Moments of Vision in Rome and New York. A painting of his hung prominently at the 1962 Seattle World's Fair, where he was also commissioned to produce a large glass-mosaic mural as a permanent addition to the fairgrounds. Galleries in New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Portland, Seattle, and Japan represented his work. In the later 1960s, as the political environment and artistic taste changed, Horiuchi remained committed to his practice and, increasingly, his search for tranquility within it. With Dusanne's retirement, he exhibited with Woodside/Braseth Gallery in Seattle into the 1990s. A large retrospective exhibition was organized by the Seattle Art Museum and the University of Oregon in 1969, his work was featured at Expo '70 in Osaka, and he received numerous awards, including a Special Commendation from the governor of Washington State (1970), the Sacred Treasure Fourth Class from the Emperor of Japan (1976), and an honorary doctorate from Seattle University (1988). He continued to paint until 1996, when he was disabled by Alzheimer's disease, and died in 1999. His work hangs in numerous public and private collections in the Northwest.

For More Information

Johns, Barbara. Paul Horiuchi: East and West . Seattle: University of Washington Press in association with Museum of Northwest Art, 2008.

Kingsbury, Martha. "Seattle and the Puget Sound." In Art of the Pacific Northwest: From the 1930s to the Present , 39-92. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press for National Collection of Fine Arts, 1974. [Describes the development of the "Northwest School" and its second-generation artists including Horiuchi.]

Nakane, Kazuko, "Facing the Pacific: Asian American Artists in Seattle, 1900-1970." In Asian American Art: A History, 1850-1970 , edited by Gordon H. Chang, Mark Dean Johnson, and Paul J. Karlstrom, 54-81. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 2008. [Places Horiuchi with an ethnic-specific art history.]

Wechsler, Jeffrey, ed. Asian Traditions, Modern Expressions: Asian American Artists and Abstraction, 1945-1970 . New York: Harry N. Abrams in association with Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, 1997. [A study of first-generation Asian American artists, including Horiuchi, and their influence at mid-century.]

Footnotes

- ↑ Horiuchi's biography is drawn from Barbara Johns, Paul Horiuchi: East and West (Seattle: University of Washington Press in association with Museum of Northwest Art, La Conner, Wash., 2008).

- ↑ Bellevue American , August 3, 1950.

- ↑ June Mukai McKivor, "Kenjiro Nomura (1896-1956)," in Kenjiro Nomura: An Artist's View of the Japanese American Internment (Seattle: Wing Luke Asian Museum, 1991), 13.

Last updated Jan. 8, 2018, 6:46 p.m..

Media

Media