Resettlement

Resettlement was a term used by the War Relocation Authority (WRA) to describe the movement of "loyal" Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans from concentration camps during World War II. The definition of resettlement has changed over time, however, and today refers more generally to the various migrations that people of Japanese ancestry undertook during and after the war. This article will focus on the group of people who left camp before 1945 to pursue education, employment, and permanent residence in the interior of the country. Other topics related to resettlement, such as " voluntary evacuation ," military service, and the return of Japanese Americans to the West Coast, are covered in separate entries.

The First Leave Programs: Education and Agriculture

Plans for moving Japanese Americans out of the camps formed as early as the spring of 1942. Though the impetus for these early leave programs originated outside the government and targeted specific populations, they laid the groundwork for the WRA's future resettlement policies.

The first leave program addressed higher education. With mass removal threatening to disrupt the college education of nearly 3,000 Nisei , private groups quickly mobilized. In May of 1942, under the direction of the American Friends Service Committee , religious leaders, educators, and government officials formed the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council to help place Nisei in colleges around the country. Educational institutions, including the University of California and the University of Washington, also helped relocate Japanese American students. As some of the first to move outside the West Coast, Nisei students encountered a range of responses. In Idaho, local officials held a group of students in protective custody following a racially motivated attack. Others transitioned to their new surroundings without incident. Yet, even those who reported positive experiences faced continual pressure to "perform both academically and socially." [1] By December of 1942, some 250 Nisei had departed camp to attend college. This number swelled to 4,300 by the end of the war.

Seasonal labor offered another avenue for leave. The war effort had depleted the agricultural workforce and industry leaders looked to Japanese American inmates to help fill the void. In May of 1942, after a month of lobbying efforts, government officials created seasonal leave, a short-term program that temporarily released Japanese Americans for agricultural work. On May 21st, the first group of fifteen workers left the Portland Assembly Center to harvest sugar beets in southeast Oregon. By mid-October, approximately 10,000 Japanese Americans were toiling in the fields. Employers had to provide transportation and housing as well as a "pledge in writing that...workers' safety would be guaranteed." [2] These formal assurances did little to shield Japanese Americans from hostile encounters. In one case, local townspeople in Utah fired over a dozen shots into a Japanese American labor camp. Despite these risks, however, many took advantage of the opportunity to leave camp and earn a wage, even if that income paled in comparison to what they could have made back home.

Determining Loyalty

The government considered these early leave programs a success. Students and seasonal workers had faced some hostility, yet their presence did not provoke widespread opposition. Further, their labor proved valuable. In September of 1942, the WRA began to formulate a more comprehensive resettlement policy with the goal of pushing "loyal" Japanese Americans out of the camps. Though releasing Japanese Americans would help ease labor shortages, the motivations for resettlement were social as well as economic. Milton Eisenhower , the first director of the WRA, along with his successor, Dillon Myer , viewed the incarceration as an opportunity to scatter loyal Japanese Americans around the country. They believed that resettlement would help put an end to the prewar Japantowns along the West Coast and facilitate the integration of Japanese Americans into white mainstream society. Permanent leave would further guard against creating a population dependent on the federal government, which Dillon Myer, in particular, feared would continue after the war.

That "loyal" Japanese Americans would be allowed to leave camp seemed to go against the very rationale behind mass removal. After all, the incarceration was rooted in the racist presumption that all persons of Japanese ancestry posed a threat to national security. Plans for resettlement did not contradict this view, however, but came about because of it. As historian Roger Daniels points out, "only after mass evacuation and incarceration had appeased the public and the politicians was the executive branch ready to assess the loyalty of the Japanese Americans." [3]

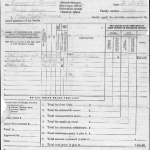

Pushing Japanese Americans out of the camps proved more difficult than anticipated, however. By the end of 1942, only 884 inmates (including students) had opted for resettlement. Though in theory the WRA encouraged leave, the application process remained "cumbersome, tedious, and time-consuming." [4] In order to relocate, Japanese Americans had to secure an outside sponsor, furnish proof of employment or education, and submit themselves to FBI background checks. Further, many were simply reluctant to leave camp, fearing the hostile reaction that would meet them on the outside. They worried about finding work and housing in unfamiliar areas as well as separating from family members who did not qualify for resettlement.

Facing these low numbers, the WRA streamlined its application procedures. In conjunction with the War Department, whose leadership was forming an all-Nisei combat team, the WRA devised an application for leave clearance , which asked inmates to declare their loyalty to the United States as well as express their willingness to serve in the U.S. armed forces. Registration, as it became known, was mandatory for all adult inmates over the age of seventeen, and provided the WRA a means to separate those they deemed "troublemakers" from the rest of the camp population. Based on the results of this flawed questionnaire, officials sorted inmates into arbitrary categories of "loyal" and "disloyal" and created divergent pathways for each. Those considered "loyal" remained in camp or left for resettlement or military service, while the so-called disloyals were segregated into separate facilities through the end of the war and, in some cases, beyond. [5]

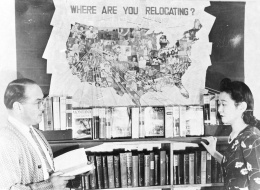

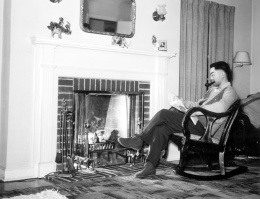

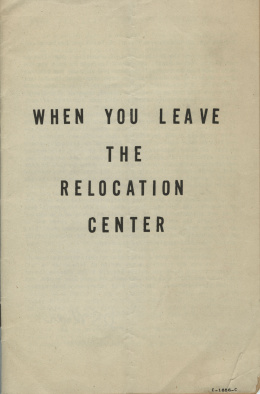

The WRA accompanied registration with a propaganda campaign to facilitate permanent leave. WRA officials and representatives toured the camps and made presentations about the opportunities that resettlement offered. Literature and photographs circulated both inside and outside the camps depicting resettlers as happily integrated into their new surroundings. These highly staged images attempted to rehabilitate Japanese Americans in the eyes of the public, showing them to be capable of blending into white middle-class society. [6] In keeping with its assimilationist goals, the WRA also counseled those leaving camp to maintain a low profile, speak only in English, and stay away from other Japanese Americans.

Resettlers

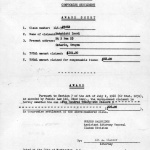

Despite the confusion and tension that registration generated, it did jump start the resettlement process. Though never as high as the WRA wanted, the number of those seeking indefinite leave slowly increased from 884 at the end of 1942 to approximately 11,000 by August of 1943. Without the lengthy background check and job requirements, inmates who submitted an application for leave clearance had to wait only a few weeks to relocate. In addition, the WRA established field offices in six regions and thirty-five sub-regions across the United States to help newly arrived Japanese Americans find housing and employment. Religious groups, charity organizations, and local civic leaders also formed volunteer resettlement committees to assist those heading east.

By the end of 1944, nearly 35,000 Japanese Americans had relocated to the outside. This group consisted overwhelmingly of young, educated Nisei; only one out of six Issei had left camp by January of 1945. The WRA steered resettlers towards Midwestern states such as Illinois, Ohio, and Michigan. By the end of the war, Chicago had emerged as the largest resettlement hub in the U.S. with 6,599 residents. [7] With employment opportunities and sizeable camp populations, Colorado, Utah, and Idaho also became popular destinations.

Reactions to these newcomers varied from place to place. Rural areas tended to be more hostile than urban centers, though Japanese Americans also faced opposition in cities. Salt Lake City residents initially welcomed Japanese Americans, but quickly grew antagonistic as the population of resettlers swelled. In Chicago, African Americans, arriving to the city in much greater numbers, often bore the brunt of overt racial animosity. [8] Yet, regardless of where they ended up, Japanese Americans consistently faced institutionalized forms of discrimination that severely limited their options.

Housing was one such arena. As Japanese Americans left camp, they encountered significant hurdles in their search for housing. Religious and charity groups provided some assistance, organizing temporary hostels for newly arriving Japanese Americans. Finding permanent shelter proved more difficult, however. With many cities already struggling to accommodate the massive influx of defense workers, Japanese Americans faced a tight housing market. In addition, discriminatory housing policies restricted their mobility. With white middle-class neighborhoods off-limits, Japanese Americans often resided in substandard housing on the edges of black and Latino districts. [9]

With employment as well Japanese Americans struggled to secure anything other than unskilled work. While the war effort generated a huge demand for labor, Japanese Americans found themselves relegated to menial positions. In rural areas, this meant agricultural or farm labor, while in the cities Japanese Americans toiled most commonly as domestics. In fact, the WRA encouraged domestic work because it came with room and board. Other occupations included factory work for men and clerical work for women, though these positions were few and far between.

On December 18, 1944, the Supreme Court ruled in Ex Parte Endo that the federal government could no longer detain loyal American citizens against their will. On January 2, 1945, the government rescinded the mass exclusion orders and opened up the West Coast to Japanese Americans not deemed disloyal. After Endo, the WRA continued to encourage dispersal, though with diminishing success. While some Japanese Americans headed to the interior to join siblings and other relatives, many more returned to the West Coast. Of the 75,000 who remained in camp in January of 1945, over two-thirds would move back west. Resettlement communities did persist, however, despite this westward migration. By the end of the war, Chicago, Denver , Salt Lake City, and New York all maintained sizeable Japanese American populations.

Legacies

While some Japanese Americans remember their resettlement experience as an adventure, exposing them to new people and places, others recall the extreme hardship and isolation that they endured. These mixed feelings reflect the ambiguity of resettlement, as both opportunity and ordeal. Conceived by the WRA as a program of dispersal, resettlement pulled Japanese Americans into unfamiliar areas of the country where they attempted to rebuild their lives in the most trying of circumstances. Despite WRA directives, resettlers managed to form meaningful relationships and communities that continue to shape Japanese American life today.

See also Return to West Coast .

For More Information

General Works on Resettlement

Austin, Allan W. "Eastward Pioneers: Japanese American Resettlement during World War II and the Contested Meaning of Exile and Incarceration." Journal of American Ethnic History 26.2 (Jan. 2007): 58–84.

Bloom, Leonard, and Ruth Riemer. Removal and Return . Berkeley: University of California Press, 1949.

Dempster, Brian Komei, ed. ' Making Home from War: Stories of Japanese American Exile and Resettlement . Berkeley, CA: Heydey Books, 2010.

Hirabayahi, Lane Ryo, and Kenichiro Shimada. Japanese American Resettlement Through the Lens: Hikaru Carl Iwasaki and the WRA's Photographic Section, 1943-1945 . Boulder: University of Colorado Press, 2009.

Kashima, Tetsuden. "Japanese American Internees Return—1945 to 1955: Readjustment and Social Amnesia." Phylon 41.2 (June 1980): 107-15.

Robinson, Greg. After Camp: Portraits in Midcentury Japanese American Life and Politics . Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012.

Thomas, Dorothy S. The Salvage Berkeley: University of California Press, 1952.

Japanese American Students

Austin, Allan W. From Concentration Camp to Campus: Japanese American Students and World War II . Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004.

O'Brien, Robert W. The College Nisei . Palo Alto, CA: Pacific Books, 1949. New York: Arno Press, 1978.

Okihiro, Gary Y., and Leslie A. Ito. Storied Lives: Japanese American Students and World War II . Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1999.

Resettlement Communities

Albert, Michael Daniel. "Japanese American Communities in Chicago and the Twin Cities." Ph.D. dissertation, University of Minnesota, 1980.

Austin, Allan W. "'A Finer Set of Hopes and Dreams': The Japanese American Citizens League and Ethnic Community in Cincinnati, Ohio, 1942–1950." In Remapping Asian American History , edited by Sucheng Chan, 87-105. Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press, 2003.

Brooks, Charlotte. "In the Twilight Zone between Black and White: Japanese American Resettlement and Community in Chicago, 1942-1945." Journal of American History 86.4 (March 2000): 1655-1687.

Conner, Nancy Nakano. "From Internment to Indiana." Indiana Magazine of History 102.2 (June 2006): 89–116.

Inoue, Miyako. "Japanese-Americans in St. Louis: From Internees to Professionals." City & Society 3.2 (Dec. 1989): 142-52.

Japanese American National Museum, ed. REgenerations Oral History Project: Rebuilding Japanese American Families, Communities, and Civil Rights in the Resettlement Era, Volume 1, Chicago Region . http://content.cdlib.org/view?docId=ft7n39p0cn&query=regenerations%20oral%20history&brand=calisphere .

Linehan, Thomas M. "Japanese American Resettlement in Cleveland during and after World War II." Journal of Urban History 20.1 (Nov. 1993): 54-80.

Taylor, Sandra C. "Leaving the Concentration Camps: Japanese American Resettlement in Utah and the Intermountain West." Pacific Historical Review 60.2 (May 1991): 169-94.

Walz, Eric. Nikkei in the Interior West: Japanese Immigration and Community Building, 1882–1945 . Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2012.

Footnotes

- ↑ Nanka Nikkei Voices: Resettlement Years, 1945-1955 (Los Angeles: Japanese American Historical Society of Southern California, 1998), 5.

- ↑ Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians , 2nd ed., (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1982; Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997), 182. Citations refer to the latter edition.

- ↑ Roger Daniels, Prisoners Without Trial: Japanese Americans in World War II (New York: Hill & Wang, 1993), 78.

- ↑ Sandra Taylor, "Leaving the Concentration Camps: Japanese American Resettlement in Utah and the Intermountain West," Pacific Historical Review 60.2 (1991): 173.

- ↑ Tule Lake , which the government transformed into a segregation center, did not officially close until March of 1946.

- ↑ Lane Ryo Hirabayashi and Kenichiro Shimada, Japanese American Resettlement Through the Lens: Hikaru Carl Iwasaki and the WRA's Photographic Section, 1943-1945 (Boulder: University of Colorado Press, 2009).

- ↑ Numbers taken from Daniels, Prisoners Without Trial , 79; Personal Justice Denied , 234.

- ↑ Charlotte Brooks, "In the Twilight Zone between Black and White: Japanese American Resettlement and Community in Chicago, 1942-1945," Journal of American History 86.4 (2000), 1675.

- ↑ Greg Robinson, After Camp: Portraits in Midcentury Japanese American Life and Politics (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 46.

Last updated Oct. 8, 2020, 4:04 p.m..

Media

Media