Tokutaro Slocum

| Name | Tokutaro "Tokie" Slocum |

|---|---|

| Born | 1895 |

| Died | 1974 |

| Birth Location | Japan |

| Generational Identifier |

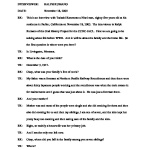

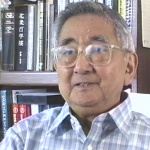

World War I veteran, citizenship activist, and Americanization advocate. Born in Japan, but raised in an adoptive American family, Tokutaro "Tokie" Slocum (1895–1974) led the fight to secure naturalization rights for Issei World War I veterans like himself. Before and after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Slocum was perhaps the most extreme of the Japanese American leaders in espousing a super patriotic stance even if it meant vilifying Japan and his fellow Issei.

Early Life and Citizenship Campaign

Tokutaro Nishimura Slocum was born in Japan in 1895 and came to the United States when he was ten. When his father moved to Canada in the hope of escaping discrimination in the U.S., young Tokie was adopted by the Slocum family of Minot, North Dakota. He went on to graduate from the University of Minnesota and enrolled in law school at Columbia, but cut off his studies to enlist to fight in World War I. As part of the 82nd Division, 328th Infantry, he took part in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive and the Battle of St. Mihiel, attaining the rank of sergeant major. He also suffered from the effects of being gassed for the rest of his life.

Like many Issei World War I veterans, Slocum saw his military service as a path to citizenship and applied in January 1921 citing the provisions of the Act of May 9, 1918, which offered naturalization to any alien who served in the armed forces in World War I. However, Slocum was turned down on the basis of the Immigration Act of 1790 and its 1870 revision that limited naturalization to a "free white person" and "aliens of African nativity and persons of African descent." Though he did eventually obtain citizenship himself, he threw his efforts into seeking federal legislation that would guarantee a path to citizenship for Asian American World War I veterans. He managed to gain the support of not only the fledgling Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), but of historically anti-Japanese groups like the American Legion and even the California Joint Immigration Committee . The Nye-Lea Act was signed into law on June 24, 1935; Slocum received the pen President Franklin D. Roosevelt used to sign the legislation into law.

Also in 1935, he married Ayako "Sally" Yabumoto (1908–91), a Nisei who grew up in New Mexico; the couple subsequently had a son and a daughter. According to Togo Tanaka , Slocum had previously been married to a white woman at a time when such unions were very rare and even illegal in many states.

War Years and Aftermath

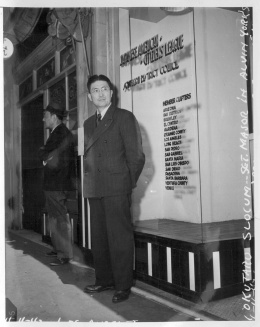

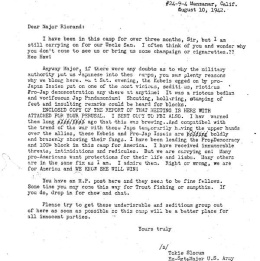

After the passage of the Nye-Lea Act, he remained a visible figure in the Japanese American community in New York and in Los Angeles, though he broke off from the JACL after having been active with it in the early 1930s. He distinguished himself by the vehemence of his patriotism even arguing that Nisei should turn in their own parents if necessary. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Slocum was among the Nisei who formed the Anti-Axis Committee in Los Angeles. He was also welcomed back to the JACL and became chair of "counter-espionage" activities in Southern California.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, he told a gathering of JACL leaders that he assisted the FBI in arresting Issei leaders:

Just as in World War I, again I went over the top. This time it was on the home front, and I led our FBI and Intelligence officers right into the den of those disloyal and traitorous elements, the Central Japanese Association. [1]

He was the only Japanese American leader to openly admit to such actions.

Despite his best efforts, his eager collaboration with the authorities did nothing to prevent the mass forced removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast. He and his family were sent to the Manzanar camp in the spring of 1942. When the rising unpopularity of JACL members and those accused of being “ inu " led to the creation of a "death list" and the severe beating of JACL leader Fred Tayama in late 1942, Slocum was among those removed from the camp and put in protective custody. He later worked for the Office of Strategic Services in the Far East Intelligence Section.

After the war, he worked for the Veterans Administration in Hawai'i before settling in Fresno, California, where he worked for the Social Security Administration until his retirement in 1958. Though Sally became active in JACL again, serving as president of the Fresno chapter, Tokie kept a low public profile while also battling health problems for years before his death on January 5, 1974. [2]

For More Information

Honda, Harry. "Tokie Was Naturalized 'Twice.'" Pacific Citizen , Dec. 19–26, 1975, A10, B4.

Hosokawa, Bill. JACL in Quest of Justice: The History of the Japanese American Citizens League . New York: William Morrow, 1982.

Muller, Eric L. Free to Die for Their Country: The Story of the Japanese American Draft Resisters in World War II . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001.

Salyer, Lucy. "Baptism by Fire: Race, Military Service, and U.S. Citizenship Policy, 1918–1935." Journal of American History 91.3 (Dec. 2004): 847–76.

Spickard, Paul R. "The Nisei Assume Power: The Japanese-American Citizen's League, 1941-1942." Pacific Historical Review 52 (May 1983): 147-74.

Takahashi, Jere. Nisei/Sansei: Shifting Japanese American Identities and Politics . Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1997.

Tamura, Eileen H. In Defense of Justice: Joseph Kurihara and the Japanese American Struggle for Equality . Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2013.

Tanaka, Togo. " A Report on the Manzanar Riot of Sunday December 6, 1942. " The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement: A Digital Archive. Bancroft Library, University of California. Call number BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder O10.12 (2/2).

Last updated July 29, 2020, 5:31 p.m..

Media

Media

![Letter from Cedrick M. Shimo to the Office of Redress Admnistration [Administration], December 4, 1990 Letter from Cedrick M. Shimo to the Office of Redress Admnistration [Administration], December 4, 1990](https://encyclopedia.densho.org/front/media/cache/a7/88/a788214a718fe6377c98198ef0311566.jpg)