Ansel Adams

| Name | Ansel Adams |

|---|---|

| Born | February 20 1902 |

| Died | April 22 1984 |

| Birth Location | San Francisco, CA |

Nature photographer and conservationist, Ansel Adams's (1902–84) heroic black-and-white photographs defined Americans' view of Yosemite, the Sierra Nevadas and the West. His 1944 book on the U.S. government incarceration camp Manzanar , Born Free and Equal, was praised by some for its moral courage and criticized by others for sympathizing with the prisoners. In the years since its publication, mixed views of this little-known book have cast Adams as either an apologist for the government's unconstitutional wartime removal and imprisonment of Japanese Americans, or as a champion of prisoners' dignity and perseverance in the face of adversity.

Before the War

Adams was born and raised among the dunes of San Francisco's South Bay, to a family of means that fell on hard times after the Panic of 1907. Hypersensitive and prone to illness, he was tutored at home and developed a love for nature early, collecting insects along Lobos Creek and exploring Baker Beach. [1] Recognizing his musical talent and intellect, his doting father hired a piano teacher and gave his 13-year-old son a year-long pass to the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition, which became his school for a year. Adams fell in love with photography after receiving a Kodak Brownie box camera from his parents when he was 14. Musically gifted enough to seriously consider becoming a concert pianist, Adams eventually chose photography as his life's pursuit. As an active member of the Sierra Club, his passions for photography, hiking, and Yosemite developed in concert. It was in Yosemite that he met the woman who became his wife, Virginia Best.

As his reputation as a photographer of Yosemite and the West grew in the 1920s and '30s, Adams formed lasting friendships with a circle of photographers, curators and other art world luminaries including Edward Weston, Alfred Stieglitz, and Georgia O'Keefe. He helped launch the influential organization of San Francisco photographers Group f/64, exhibited his work in New York and published the book Making a Photograph .

Wartime Years

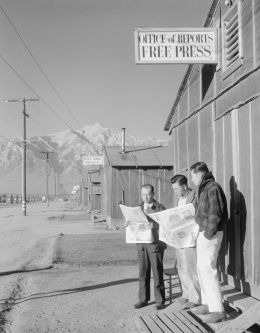

When the United States entered World War II in 1941, Adams was too old to fight yet was unsatisfied with the civil wartime tasks assigned to him. Ralph Merritt, a friend from the Sierra Club and project director at Manzanar, suggested that he document the camp. [2] The book, Born Free and Equal: Photographs of the Loyal Japanese Americans at Manzanar Relocation Center , was published in June 1944, by U.S. Camera , a magazine devoted to art and news photography to which Adams contributed photographs and articles. The cheaply printed red paperback sold for two dollars and featured 64 of Adams's photographs taken during his four visits to the prison camp between October 1943 and July 1944, alongside text he wrote himself. It was among the top ten books sold in San Francisco that year, but was poorly distributed beyond the Bay Area. [3] In his later years, Adams claimed the military had confiscated a large number of copies and destroyed them because of the book's perceived anti-Americanism. [4]

Differing Interpretations of Born Free and Equal

Troublesome for some viewers today is the fact that the photographs of Born Free and Equal reveal none of the "despair, bewilderment and misery" that prisoners experienced, and that Adams acknowledged were present in photographer Dorothea Lange 's images of Manzanar. [5] In Adams's photographs, many of them close-up portraits, inmates express a sense of optimism, possibility and a reverence for nature. Descriptions of prisoners' vocations are interspersed with heroic landscapes, suggesting spiritual redemption through nature's beauty.

Intended to serve as a ringing endorsement of the industry and forbearance of the imprisoned Japanese Americans, Adams scrupulously avoided the inclusion of sentiments of anger, shame or bitterness in his subjects, omitting images of the members of the "no-no" faction, those who refused to promise to serve in combat for the U.S. armed forces and refused to renounce allegiance to the Japanese Emperor.

Critics including Karin Becker Ohrn called Adams an "apologist intent on showing the success of the internment," and his photographs "insights into the officially sanctioned view of the internment at the time." [6] Judith Fryer Davidov criticized Adams for glossing over the uglier aspects of the prison camps and the fundamental injustice of incarcerating people because of their Japanese ancestry, and viewed the cooperative Nisei as being complicit in creating an image of willing sacrifice for a greater cause. Adams's images of "accommodationist Nisei—those who demonstrated their submission to captivity by working to make the spaces in which they were imprisoned more comfortable and attractive, or their patriotism by enlisting in the armed forces—fit perfectly with the official presentation of the concentration camps as humane, orderly, and even beneficial to the internees," [7] wrote Davidov.

Others viewed the photographer's work at Manzanar more sympathetically. A 1977 exhibition and book, "Two Views of Manzanar," created by three fine arts graduate students at UCLA, Graham Howe, Patrick Nagatani and Scott Rankin, show Adams's photographs alongside those of Manzanar inmate and professional photographer Toyo Miyatake . Howe has called Adams's Manzanar photographs "his most compassionate body of work." [8]

Constitutional lawyer John Armour and Associated Press photo editor Peter Wright, in their 1988 book Manzanar , described Adams as being motivated by a sense of social justice, and his message incompatible with the war-mongering sentiment of the times. The book includes an essay by John Hersey, who wrote, "the book's implicit message of guilt and shame did not go down well with a public still hungry for the unconditional surrender of a tenacious enemy." [9]

More recently, Adams expert Anne Hammond described Adams as being strongly influenced by the liberal voices of his friend Lange and the writings of Carey McWilliams , a lawyer and defender of the civil rights of the imprisoned Japanese. Adams's goal, wrote Hammond, was to help publicize the need for re-integration of Japanese Americans into mainstream society after the war. [10] Historian Jasmine Alinder has written that Adams's intent was to stress both the loyalty of the prisoners and to demonstrate his belief in the "power of nature to work powerful social change." [11]

Postwar Years

Born Free and Equal was largely forgotten after World War II ended, though Adams donated his Manzanar photographs to the Library of Congress. They were eliminated from his oeuvre by The Ansel Adams Trust, which grants reproduction rights and safeguards the artist's reputation. Adams's activities included documenting the country's national parks, consulting for the Polaroid company, lecturing, and promoting both creative photography and nature conservation. He continued to photograph as well, his style going in and out of vogue. In 1974 the Metropolitan Museum of Art mounted a retrospective show of his work. He died in April 22, 1984 at the age of 82.

For More Information

Finding Aid to the Ansel Adams Manzanar War Relocation Center Photographs. Library of Congress.

Adams, Ansel. Born Free and Equal: the Story of Loyal Japanese-Americans . New York: U.S. Camera, 1944. Digitized copy.

———. Born Free and Equal: the Story of Loyal Japanese Americans, Manzanar Relocation Center, Inyo County, California . 1944. Bishop CA: Spotted Dog Press, 2002.

———. An Autobiography . New York: Little, Brown and Company, 1996.

———. Letters 1916-1984 . New York: Little Brown and Company, 1996.

Alinder, Jasmine. Moving Images: Photography and the Japanese American Incarceration . Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2009.

Armor, John, and Peter Wright. Manzanar . Commentary by John Hersey. New York: Times Books, 1988.

Davidov, Judith Fryer. "'The Color of My Skin, the Shape of My Eyes': Photographs of the Japanese-American Internment by Dorothea Lange, Ansel Adams, and Toyo Miyatake." The Yale Journal of Criticism 9:2 (fall 1996): 223–44.

Hammond, Anne. Ansel Adams at Manzanar . Honolulu: Honolulu Academy of Arts, 2006. In connection with the exhibition "Ansel Adams at Manzanar" at the Honolulu Academy of Art, September 7–October 29, 2006, and at the Japanese American National Museum November 11, 2006–February 18, 2007.

Higa, Karin, and Tim B. Wride. "Manzanar Inside and Out: Photo Documentation of the Japanese Wartime Incarceration." In Reading California: Art, Image, and Identity, 1900–2000 . Edited by Stephanie Barron, Sheri Bernstein, and Ilene Susan Fort. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000. 314–37.

Matsumoto, Nancy. "Documenting Manzanar." Discover Nikkei, (June 27, 2011- October 24, 2011).

Ohrn, Karin Becker. "What You See Is What You Get: Dorothea Lange and Ansel Adams at Manzanar." Journalism History 4.1 (spring 1977): 14–22, 32.

Robinson, Gerald H. Elusive Truth: Four Photographers at Manzanar . Nevada City, CA: Carl Mautz Publishing, 2002.

Footnotes

- ↑ Ansel Adams, An Autobiography (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 1996), 10.

- ↑ Jasmine Alinder, Moving Images: Photography and the Japanese American Incarceration (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2009), 45-46.

- ↑ Anne Hammond, Ansel Adams at Manzanar (Honolulu: Honolulu Academy of Arts, 2006), v.

- ↑ Alinder, Moving Images , 72.

- ↑ Adams, An Autobiography , 10.

- ↑ Karin Becker Ohrn, "What You See Is What You Get: Dorothea Lange and Ansel Adams at Manzanar," Journalism History 4.1 (spring 1977), 19.

- ↑ Judith Fryer Davidov, "'The Color of My Skin, the Shape of My Eyes': Photographs of the Japanese-American Internment by Dorothea Lange, Ansel Adams, and Toyo Miyatake," The Yale Journal of Criticism 9.2 (fall 1996), 233.

- ↑ Interview with Nancy Matsumoto, May 2, 2008.

- ↑ John Hersey, "A Mistake of Terrifically Horrible Proportions," in John Armor and Peter Wright, Manzanar (New York: Times Books, 1988), 10.

- ↑ Hammond, Ansel Adams at Manzanar , 3-4, 7.

- ↑ Alinder, Moving Images , 44.

Last updated Nov. 30, 2023, 5:44 p.m..

Media

Media