December 7, 1941

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese navy launched a surprise military attack against the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor located on the island of O'ahu. The attack on Pearl Harbor was intended to neutralize the United States Pacific Fleet as the Japanese expanded throughout the Pacific region. Despite numerous historical precedents for unannounced military action, the lack of any formal warning by Japan led President Franklin D. Roosevelt to proclaim December 7, 1941, "a date which will live in infamy." The attack on Pearl Harbor, not only brought America into World War II, but raised suspicions of the large Japanese communities on West Coast of the United States and in Hawai'i. However, the changes brought by war were first immediately felt by residents of O'ahu in the hours and days following the attack. [1]

The Approach and the Attack

At 3:24 a.m. on December 7, 1941, the minesweeper Condor sighted a submarine periscope off the entrance to Pearl Harbor. Since this was an area where no American submarine traveled submerged, the Condor immediately notified the destroyer Ward , which searched the waters for an hour and a half without success. Nearly three hours later, the destroyer answered a similar alert from the target repair ship Antares and this time located the submarine, apparently trailing the Antares into Honolulu Harbor. The Ward fired on the intruder—the first American shots of World War II—and the crippled submarine went down.

As the Ward was reporting the incident to the 14th Naval District headquarters, two army privates were completing their three-hour training period at an isolated radar station in the hills between Waialua and Kahuku when they discovered a large number of planes approaching O'ahu from three degrees east of north at a distance of 132 miles. A lieutenant who was serving his second morning of observation assumed that the planes were the B-17s scheduled to fly in from the Mainland and dismissed the matter.

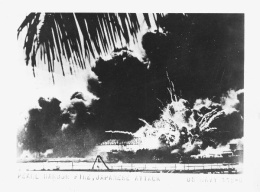

Thus, as early as 6:30 a.m., two Japanese reconnaissance planes flew over O'ahu. They were followed by 360 planes that Japanese carriers 200 miles to the north had launched in three waves. Most of the planes approached the Pearl Harbor area directly from the sea. At about 7:57 a.m., a score of fighters swooped down from the sky to within twenty feet of the ground at the Marine Corps Air Station at 'Ewa, firing on the forty-nine planes closely lined up on the field and riddling them with bullets before heading to Pearl Harbor. Japanese dive bombers immediately targeted Ford Island, in the center of Pearl Harbor, destroying thirty-three of the seventy planes on the field. Japanese pilots then besieged the heavy vessels in "battleship row," adjacent to Ford Island. Almost simultaneously, Japanese fighters attacked Hickam Field next to Pearl Harbor, Kāne'ohe Naval Air Station on the windward side of O'ahu, and Wheeler Field adjoining Schofield Barracks in central O'ahu.

In the first half-hour, Japanese pilots had inflicted significant damage to major American military installations on O'ahu. All seven battleships—the West Virginia , California , Arizona , Tennessee , Pennsylvania , Nevada , and Oklahoma —had been hit at least once, many sustaining fatal damage. In all, six ships were sunk, twelve were severely damaged, and others suffered minor blows. Hangars, machine shops, guard houses, and barracks were also hit; 2,335 American servicemen, mostly navy personnel, perished. By contrast, Japanese losses were minimal, with twenty-nine aircraft and five midget submarines damaged or destroyed, and sixty-five servicemen killed or wounded. Fires broke out throughout the city including one at the Lunalilo School first aid station. A building next to the school had caught fire and some of the residents had died, trapped behind a wall of flames. Fifty-seven civilians died on O'ahu that day, and another 280 were injured in fires caused by American anti-aircraft action. [2]

The Aftermath of the Attack

Soon, radio stations were broadcasting orders to the residents of O'ahu: "Do not use your telephone. The island is under enemy attack. Do not use your telephone. Stay off the streets. Keep calm…In the event of an air raid, stay under cover." Governor Joseph Poindexter came on the radio to proclaim a state of emergency, and, at 11:41 a.m., the army ordered all commercial radio stations off the air, fearing that Japanese planes could navigate by their signals during another attack. Later that day, the stations returned to the air to announce that Hawai'i was now under martial law . The statement was broadcast three times: twice in English, once in Japanese. [3] Poindexter also ordered the mobilization of a Territorial Guard that day. Subsequently, the University of Hawai'i's Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC) was called to duty and its members became the nucleus of the new Hawaii Territorial Guard that was primarily an "anti-sabotage force."

With martial law instituted, constitutional liberties were suspended. Civilian courts were closed, and all government functions—federal, territorial, and municipal—were placed under army control. The commanding general declared himself the "military governor" of Hawai'i, and controlled the entire civilian population with absolute discretionary powers as a state of emergency had been declared.

Rumors and Uncertainty in Wartime Hawai'i

Contributing to the atmosphere of anxiety and uncertainty that justified the imposition of martial law were rumors about those within the Japanese population who might engage in sabotage or espionage in the event of an invasion or a further attack. Immediately after the attack, it was alleged that Japanese plantation workers had cut arrows in the cane fields to direct Japanese flyers to Pearl Harbor or had set cane fires as signals. Rumors also circulated that Japanese pilots who had been shot down were found with McKinley High School and University of Hawai'i rings, implying they were former residents of Hawai'i. Newspapers reported that Japanese parachutists had landed on O'ahu and that the city water supply had been contaminated, along with other general acts of sabotage. [4] Although these rumors remained unsubstantiated, officials eventually detained 1,569 individuals it considered suspicious or dangerous of which 1,444 were of Japanese descent.

The presence of so many "undesirables" in an important military location in a time of war became the justification for martial law and for the internment of nearly 1,500 Japanese, who were sent first to camps in 'Ewa and then to the continental United States. Some historians have claimed that martial law and internment were unnecessary as no one was ever convicted of espionage or sabotage. Others have argued the opposite case, claiming that martial law prevented further acts such as the Battle of Ni'ihau. This singular event that involved the collaboration between a Japanese pilot and Japanese American, served to cast doubt on the loyalty of the nearly 160,000 Japanese on the Islands. [5] In particular, the approximately 35,500 Japanese aliens, twenty-two percent of the Japanese population in Hawai'i, were immediately suspect owing to their Japanese citizenship.

The Mobilization of the Japanese Community

To prove their loyalty, the Japanese responded to the war with extensive efforts to mobilize the Japanese community in Hawai'i and to contribute to the overall United States war effort. Prior to the war, some Nisei and non-Japanese had formed the Committee for Interracial Unity in Hawaii, a multiethnic group of civic and military leaders that included Hung Wai Ching , Charles Loomis, and Shigeo Yoshida , who were appointed to the Public Morale Section, first with the Office of Civilian Defense and a month later under the Office of the Military Governor. Under the Morale Section , various organizations were formed within different ethnic communities, such as the Emergency Service Committee , that was organized to work with the Japanese community. Members of this group worked as liaisons with the military on matters affecting the Japanese community and assured the military of the complete loyalty of the Japanese population. They disseminated information at 209 meetings, contacting approximately 10,000 individuals from February through December 1942, relieving community anxieties during a period when authorities had suspended Japanese radio broadcasts and newspapers. [6]

In addition to collective activities, many Japanese also responded through individual demonstrations of loyalty. Often holding down more than one job, many Japanese in the islands served as block wardens, Red Cross workers, fire fighters, medical workers, and laborers. They responded to urgent pleas for blood by hosting numerous blood drives and encouraged the purchase of war bonds. As block wardens, they were responsible for patrolling their areas, investigating fire hazards, and enforcing the 6:00 p.m. curfew and blackout regulations established under martial law. Volunteers also manned first-aid stations and the blood bank, and provided emergency ambulance services. In fact, the 800 volunteers who had received emergency medical training under the United Japanese Society in Honolulu went directly from their December 7, 1941, certification ceremonies to the aid of the wounded at Pearl Harbor.

As members of the kiawe corps on O'ahu and Kaua'i, and of the Menehune Minutemen on the Big Island, Japanese volunteers cleared kiawe thickets for evacuation and military camps, built trails, and strung barbed wire along the coastline. [7] On Sundays, Japanese women devoted their free time to Red Cross activities, such as folding bandages and knitting woolen socks. Others joined the Women's Division of the Office of Civilian Defense (OCD.) and studied safety measures, disseminated necessary information, and worked on special projects such as Christmas gifts for servicemen. Some young Japanese women even expressed their patriotism by entertaining off-duty soldiers at dances held in Waialua. Although many of these activities were sincere expressions of patriotism, they were also efforts to deflect the suspicion focused on them as a result of their Japanese ancestry.

In order to prove their loyalty and appear as "American" as possible, the Japanese replaced Japanese radio programs and films with English programs and American films, and a "Speak-American" campaign was launched in the Japanese community. [8] Many Japanese families also removed family heirlooms from their houses and destroyed them for fear that they would be used as incriminating evidence at an internment hearing. Additionally, many Japanese candidates who had previously been politically active elected not to run for public office during the war because of the politically volatile situation. As one Japanese politician observed, "A kettle that is already boiling should not boil over." [9] Japanese voters themselves hesitated to support Japanese candidates for fear that it would seem the Japanese community was trying to take over the government. The Japanese community did not want to exacerbate already strained race relations in Hawai'i, as the war provided the opportunity for other ethnicities to express long-standing racial antagonism toward the Japanese.

Although persons of varying ethnic backgrounds had lived and worked side-by-side for many years, there was an undercurrent of anti-Japanese feeling even before December 7. The Japanese attack and the Pacific War caused these latent feelings to surface. The Koreans disliked the Japanese because Japan had subjugated Korea; the Filipinos were angered by the Japanese invasion of their homeland. Others had doubts about the loyalty of Japanese Americans because they followed Japanese customs, went to language schools, and were generally clannish. "Once a Jap, always a Jap" was a phrase often heard in wartime Hawai'i. [10] Many Japanese understood the hostility and suspicion directed at them as this tension-filled situation ignited racial fears and hostilities.

Conclusion

To many, the Pearl Harbor attack seemed to confirm long-standing fears of the Japanese, enabling the expression of latent anti-Japanese sentiment to emerge both in Hawai'i and the United States. Pearl Harbor not only marked America's entry into World War II, but it also initiated a war within America's own borders to control and contain a population of "undesirables." Martial law and internment reflected the depth of American fears of the Japanese and their assumed disloyalty by virtue of their race that was highlighted in the events of December 7, 1941.

For More Information

Bailey, Beth and David Farber. The First Strange Place: Race and Sex in World War II Hawai'i . Baltimore: John Hopkins Press, 1992.

Dye, Bob ed. Hawai'i Chronicles III: World War Two in Hawai'i, From the Pages of Paradise of the Pacific . Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2000.

An Era of Change: Oral Histories of Civilians in World War II Hawai'i . Honolulu: Center for Oral History, Social Science Research Institute, University of Hawai'i at Mānoa, 1994.

"Pearl Harbor Raid, December 7, 1941." Naval History and Heritage Command.

Footnotes

- ↑ Research for this article was supported by a grant from the Hawai‘i Council for the Humanities .

- ↑ Gwenfread Allen, Hawaii's War Years: 1941-1945 (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1971), 7.

- ↑ Allen, Hawaii's War Years , 9-10.

- ↑ "Police Say No Evidence of Parachutists," Honolulu Star-Bulletin , December 8, 1941, 2; "Police Probe Reports of Parachutists," Honolulu Star-Bulletin , December 8, 1941, 2; "City Water Is Safe to Drink, Ohrt Announces," Honolulu Star-Bulletin , December 8, 1941, 2; "Sabotage Reported in Waikiki Area," Honolulu Star-Bulletin , December 7, 1941, 3.

- ↑ Allan Beekman, The Niihau Incident: The True Story of the Japanese Fighter Pilot Who, After the Pearl Harbor Attack, Crash Landed on the Hawaiian Island of Niihau and Terrorized the Residents (Honolulu: Heritage Press of the Pacific, 1982), 83; "Hawaiian Who Killed Japanese Aviator on Niihau Isle Honored," Honolulu Advertiser , June 7, 1943, 2.

- ↑ Dorothy Ochiai Hazama and Jane Okamoto Komeiji, Okage Same De: The Japanese in Hawai'i 1885-1985 (Honolulu: Bess Press, 1986), 147; Report of Second Oahu Conference of Americans of Japanese Ancestry, January 28, 1945 (Honolulu: n.p., 1945).

- ↑ Allen, Hawaii's War Years , 91.

- ↑ Ibid., 351.

- ↑ Theon Wright, The Disenchanted Isles: The Story of the Second Revolution in Hawaii (New York: The Dial Press, 1972), 108.

- ↑ Hazama, Okake Same De , 130.

Last updated Dec. 19, 2023, 6:10 p.m..

Media

Media