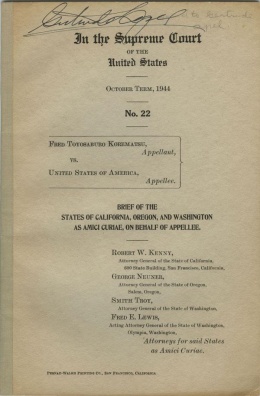

Korematsu v. United States

Landmark Supreme Court case concerning the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. Fred Toyosaburo Korematsu , who refused to leave his home in San Leandro, California, was convicted of violating Exclusion Order Number 34, and became the subject of a test case to challenge the constitutionality of Executive Order 9066 in 1942, along with fellow plaintiffs Min Yasui and Gordon Hirabayashi . After the lower court ruled against Korematsu and sentenced him to five years' probation, he filed an appeal with the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, and later, to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Court's final decision upheld Korematsu's conviction by a vote of six to three and downplayed the role of racial discrimination in the exclusion order. [1]

Background and Supreme Court Decision

Korematsu was born on January 30, 1919, to Japanese parents who ran a plant nursery in Oakland, California. He worked as a shipyard welder after graduating from high school until he lost his job after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. He was 22 when the U.S. plunged into war. On May 9, 1942, his parents and three brothers reported to the Tanforan Assembly Center , but Korematsu stayed behind with his Italian-American girlfriend. In an attempt to disguise his racial identity, he assumed the alias Clyde Sarah and claimed to be of Spanish and Hawaiian descent. He also underwent minor plastic surgery on his eyes to appear European American. His refusal to comply with the evacuation order led to his arrest on May 30, 1942.

While in San Francisco county jail, Ernest Besig of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) approached Korematsu to become the test case to challenge the constitutionality of the government's removal and confinement of Japanese Americans. After spending two and a half months in jail, Korematsu was released when Besig paid his $5,000 bail. Korematsu was then immediately handcuffed by military authorities and sent to Tanforan. He later recounted his decision to sue in an interview with the New York Times : "I didn't feel guilty because I didn't do anything wrong... Every day in school, we said the pledge of the flag, 'with liberty and justice for all,' and I believed all that. I was an American citizen, and I had as many rights as anyone else." [2] On September 8, 1942, the federal district court convicted Korematsu of defying military orders. He was "released" on probation and was forced to move to Topaz , Utah, from which he appealed his case to the U.S. Supreme Court. Back at the prison camp, he was something of a pariah. Fellow prisoners branded him as a troublemaker, while the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) would have nothing to do with him until his case reached the Supreme Court.

In October 1944, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments for the Korematsu case along with Mitsuye Endo's habeas corpus petition challenging the army's unlawful detention. It announced its decision on both cases on December 18, 1944. In its opinion on the Korematsu case, the high court accepted the army's justification of "military necessity" and sided with the government. The Endo case resulted in victory, but sidestepped the question of constitutional rights by holding only the War Relocation Authority (WRA) accountable; being a law-abiding citizen, the WRA had no legal grounds to detain her. (See Ex parte Mitsuye Endo (1944) .) The day before the Supreme Court decisions, traditionally announced on Mondays, the War Department preempted the verdicts with a press release that it was revoking the mass incarceration order and freeing the prisoners effective January 2, 1945. [3]

Justice Hugo Black delivered the court's opinion: "Korematsu was not excluded from the military area because of hostility to him or his race. He was excluded because we are at war with the Japanese Empire," and "because they decided that the military urgency of the situation demanded that all citizens of Japanese ancestry be segregated from the West Coast temporarily." In essence, the court affirmed the inevitability of bowing to military demands during a time of war. Twenty-three years later, in an interview with the New York Times , Justice Black reiterated his conviction that he would "do precisely the same thing today." "They all look alike to a person not a Jap," he explained, "Had [Japan] attacked our shores, you'd have a large number of them fighting with the Japanese troops. And a lot of innocent Japanese-Americans would have been shot in the panic." [4]

In their dissent, three justices saw a clear violation of Korematsu's constitutional rights. Justice Owen Roberts, who had previously upheld Hirabayashi's curfew restrictions, made it clear that Korematsu's was "not a case of keeping people off the streets at night." The Supreme Court was about to "convict a citizen...for not submitting to imprisonment in a concentration camp, based on ancestry, and solely because of his ancestry, without evidence or inquiry concerning his loyalty and good disposition towards the United States." The contradictory nature of the exclusion orders, making him a criminal if he stayed in the military area where he lived and later, if he left, were "nothing but a cleverly devised trap to accomplish the real purpose of the military authority, which was to lock him up in a concentration camp." [5]

Justice Frank Murphy contended that "No adequate reason [was] given for the failure to treat these Japanese Americans on an individual basis by holding investigations and hearings to separate the loyal from the disloyal, as was done in the case of persons of German and Italian ancestry." He further questioned the military's claim of urgency when nearly four months had elapsed after Pearl Harbor before the first exclusion order was issued. A case of imminent danger would have warranted a declaration of martial law. "I dissent, therefore, from this legislation of racism," he stated, "Racial discrimination in any form and in any degree has no justifiable part whatever in our democratic way of life." [6]

Justice Robert Jackson, who later served as prosecutor at Nuremberg, warned that "once a judicial opinion rationalizes such an order to show that it conforms to the Constitution, or rather rationalizes the Constitution to show that the Constitution sanctions such an order, the Court for all time has validated the principle of racial discrimination in criminal procedure and of transplanting American citizens." Expressing his skepticism toward the War Department's justification for incarceration, he likened the principle of military necessity to "a loaded weapon," setting a legal precedent of unlimited wartime executive power with far-reaching implications for the future. [7]

Aftermath and Legacy

In 1982, with newly uncovered documents by law historian Peter Irons, Korematsu, Hirabayashi, and Yasui filed a writ of error coram nobis to their respective U.S. district courts. This legal procedure is designed to vacate wrongful convictions in cases of governmental misconduct such as withholding important information or presenting false evidence at a trial. (See coram nobis cases .) The government files disclosed that the Justice Department lawyers who handled these Supreme Court cases had complained that their superiors were suppressing evidence and lying to the justices, but their complaints had been ignored. [8]

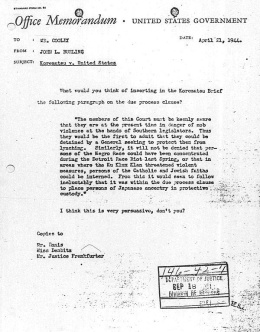

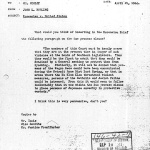

At issue was John L. DeWitt's Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 , with which he had justified his recommendation for mass incarceration. Back in 1943, when attorneys Edward Ennis and John Burling were reviewing the report for use in the government's Supreme Court briefs in Hirabayashi and Yasui , they found that DeWitt's argument of "military necessity," specifically his claims of Japanese American espionage activity and shore-to-shore signaling, were not only false but had been refuted by the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI), the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). Burling attempted to add a footnote alerting the Justice Department's disagreement with the Final Report. In response, War Department officials halted its publication, altered the footnote, and concealed the existence of a prior version, which would have undermined DeWitt's credibility. After burning the drafts, memorandums, and galley proofs of the original report, an extremely diluted version was presented to the Supreme Court in the Korematsu case after its public release in 1944. [9]

After a year of litigation in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, Judge Marilyn Hall Patel set a hearing for November 10, 1983. Korematsu stood before the court and stated: "As long as my record stands in federal court, any American citizen can be held in prison or concentration camps without a trial or a hearing." Indeed, as recently as 1971, suspected subversives could still be detained without due process of law under the McCarran Internal Security Act of 1950, an anti-communist legislation of the McCarthy era. In a surprise move, Judge Patel ruled from the bench and overturned Korematsu's conviction. In her written ruling, she underscored the significance of the Korematsu case: "It stands as a caution that in times of distress the shield of military necessity and national security must not be used to protect governmental actions from close scrutiny and accountability." Patel's decision led to Hirabayashi and Yasui's successful coram nobis petitions and influenced the passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 that granted reparations to Japanese Americans who were incarcerated during World War II. The Supreme Court decision still stands, but the federal Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians concluded in its 1983 report, " Personal Justice Denied ," that the Korematsu case "lies overruled in the court of history." [10]

For More Information

Hosokawa, Bill. Nisei: The Quiet Americans . Boulder: University of Colorado Press, 2002.

Irons, Peter. Justice at War: The Story of the Japanese American Internment Cases . New York: Oxford University Press, 1983.

———. Justice Delayed: The Record of the Japanese American Internment Cases . Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1989.

Korematsu Institute. http://korematsuinstitute.org/ . [Biography of Korematsu and his legal team and Judge Marilyn Hall Patel's decision at the Korematsu Institute for Civil Rights and Education.]

Of Civil Rights and Wrongs: The Fred Korematsu Story . Directed by Eric Paul Fournier. New York: P.O.V./American Documentary, Inc., 2000.

Toyosaburo Korematsu v. United States . 323 U.S. 214 (1944). http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/scripts/getcase.pl?court=us&vol=323&invol=214 . [Supreme Court decision against Korematsu.]

Footnotes

- ↑ Peter Irons, Justice Delayed: The Record of the Japanese American Internment Cases (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1989), 76.

- ↑ Richard Goldstein, Fred Korematsu Obituary, New York Times , April 1, 2005.

- ↑ Bill Hosokawa, Nisei: The Quiet Americans (Boulder: University of Colorado Press, 2002), 427; Encyclopedia of Japanese American History: An A-Z Reference from 1868 to the Present , ed. Brian Niiya (New York: Facts on File, 2001), 160.

- ↑ Hosokawa, Nisei , 427; Roger Daniels, Asian America: Chinese and Japanese in the United States since 1850 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1992), 278.

- ↑ Hosokawa, Nisei , 428.

- ↑ Ibid., 428-429.

- ↑ Ibid., 429.

- ↑ Irons, Justice Delayed , 125.

- ↑ Irons, Justice Delayed , 128-129; Encyclopedia of Japanese American History , 252.

- ↑ Claudia Luther, Fred Korematsu Obituary, Los Angeles Times , April 1, 2005.

Last updated July 29, 2020, 5:37 p.m..

Media

Media