Military Intelligence Service Language School

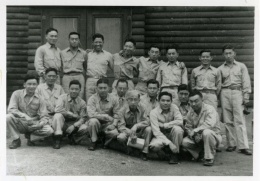

During World War II, fighting in the Pacific theater of the war necessitated Japanese linguists for translation, interpretation, and combat purposes. When American military officials discovered the lack of skilled Japanese linguists among Caucasian personnel, they recruited Nisei soldiers to attend the Military Intelligence Service Language School (MISLS) that was first established in the Presidio in San Francisco and later at Camp Savage and Fort Snelling, Minnesota. The MISLS was critical in producing skilled linguists who were essential in World War II and later the occupation of Japan. [1]

The Creation of the MIS Language School

On the eve of World War II, diplomatic talks between Japan and the United States slowly deteriorated. As the possibility of war with Japan steadily grew during the summer of 1941, officials in the United States War Department realized significant deficiencies in America's intelligence capabilities regarding Japan. There were dishearteningly few Caucasian personnel qualified in the Japanese language, and there was little time to train additional translators given the rapid approach of war. [2] While military officials recognized that second-generation Japanese Americans likely comprised the best candidates for intelligence training, officials initially distrusted the Nisei and resisted their inclusion in the armed forces. Further, even within these small numbers of Japanese Americans in the military, Japanese linguists skilled in interpretation, translation, and interrogation proved alarmingly scarce. In an initial survey of 3,700 Nisei, MISLS officials deemed only three percent as accomplished linguists. They considered another four percent or so proficient and found that another three percent could only be useful after a prolonged period of training. [3] The vast majority of Nisei seemed more American than Japanese and were less fluent in Japanese than previously believed. It became evident to military officials that a special training school would be required to transform the Nisei into competent Japanese linguists.

Given the importance of discovering or developing qualified Japanese interpreters, a small group of army officers pushed for the creation of an intelligence unit in anticipation of war with Japan. Among them were Major Carlisle C. Dusenbury, a former Japanese language student on duty in the Intelligence Division, and Lieutenant Colonel Wallace Moore, whose missionary family had served in Japan. [4] Colonel Rufus S. Bratton, also a former language student and military attaché in Tokyo, served as chief of the Far Eastern Branch, Intelligence Division, and subsequently approved the plans formulated by these two men. The Training and Operations Division (G-3), which supervised the army's school system, also provided support. In the latter part of 1941, War Department officials reluctantly budgeted $2,000 to start the first Army Japanese Language School under the authority of Lieutenant Colonel (later Brigadier General) John Weckerling. [5] After securing meager funds for the school, officials searched for eligible candidates to enroll in intensive language training. Nisei personnel were conscripted through the Selective Service, screened, and stationed at various army units on the Pacific coast. Each soldier was personally interviewed and examined before being allowed to join the ranks of one of the most selective military units. [6]

The First Language School Classes

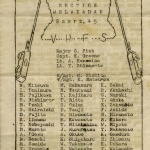

On November 1, 1941, a little over a month before the outbreak of war, the first class of sixty students taught by four Nisei instructors began training in a small abandoned aircraft hangar on Crissy Field at the Presidio in San Francisco. The hangar served as the office, faculty room, classrooms, and barracks. Initially orange crates and boxes functioned as desks and chairs and, given the short supply of texts, trainees studied from mimeographed sheets. Among the sixty students were fifty-eight Nisei and two Caucasian soldiers, E. David Swift and John Alfred Burden. [7] Although Burden was fluent in Japanese, like many of his classmates he had no prior knowledge of military terminology and struggled in his studies. As Burden recalled:

I didn't know anything about the Japanese military, so I had to study very hard. Head Instructor John Aiso hounded me. At first I got frustrated. I would ask a question, and his explanation would be even worse than the original problem. Later, he told me, "If I gave you a pat answer, you wouldn't learn anything. By pushing you, you're forced to get that much better." He was a good man. He really worked on me. [8]

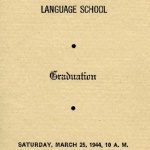

The instructors, both Caucasians and Japanese, pushed the recruits to become proficient in their linguistic skills in an unprecedentedly short period of time. Burden himself went overseas after a five month "crash course" in Japanese military vocabulary, as did two brothers, Takashi and Takeo Kubo, and ten Counter Intelligence Corps men. Eventually only forty-five students graduated in May 1942, as one-quarter of the class failed due to the rigorousness of the program and the considerable demands placed on the soldiers.

The intensity of the training at the language school and the urgency of war placed additional pressures on both instructors and students. Classes began at 8:00 a.m., ran for ten hours a day, and many students studied until "lights out" at 11:00 p.m. Despite this regulation, some trainees studied by flashlight under their blankets. Others continued their language work in the latrine, the only place lit at night. This tradition persisted at the next location of the language school, where it became necessary for officers at Camp Savage to patrol the school area to prevent extra studying after lights were extinguished at night. Those already proficient in their studies helped those who were struggling, and many put in long hours teaching and learning Japanese. The diligence of the students not only reflected their determination to succeed but also the difficulty of the coursework.

Language School Curriculum

The basic curriculum of the language school included reading, writing, and conversation, and extended to the study of Japanese law, society, and culture. An understanding of Japanese army jargon, military codes, and tactics was also required. In addition, soldiers had to master techniques in intercepting communications, interrogating, and interpreting that required knowledge in sōrōbun , a style for personal letters that originated in the Edo period (1600–1868). Ordinary soldiers and even non-commissioned officers in the Japanese army used sōrōbun , necessitating knowledge of this language. In order to analyze seized documents, soldiers additionally needed to learn to read sōsho , a flowing cursive Japanese writing that was difficult to master even for students who had studied Japanese for years. [9]

By the time the first class of recruits completed the program, the staff had increased to eight civilian instructors, who were in turn joined by recent graduates. Owing to the need for larger teaching facilities, and because of the mass exclusion of Japanese Americans from the West Coast, the Fourth Army Intelligence School moved to Camp Savage in Minnesota, where it came under the direct jurisdiction of the War Department. The first official MISLS class began in Minnesota on June 1, 1942, with 200 students and eighteen instructors laboring in cabins formerly used as state homes for indigent elderly men. Colonel Kai E. Rasmussen gained the appointment as the commandant of the school.

The Contributions of MIS Linguists

Close bonds of brotherhood developed among the men at the language school that remained with them even as they departed for different areas of combat. As the importance of their services in the successful prosecution of the war against Japan became recognized, field commanders began to demand additional MIS linguists. The plea for MIS personnel came not only from all branches of the American forces but also from the larger Allied forces throughout the Pacific and Southeast Asia. To meet this increasing need for linguists, the MISLS recruited several hundred volunteers from the mainland detention camps and from Hawai'i. In addition, 200 members of the 100th Infantry Battalion training at Fort McCoy, Wisconsin, were transferred to the MISLS in December 1942. In 1943, MIS students were also recruited from the 442nd Regimental Combat Team training at Camp Shelby, Mississippi.

In August 1944, the language school had outgrown Camp Savage and relocated to the larger facilities at nearby Fort Snelling, Minnesota. Compared to earlier enlistees, the students currently entering the program were younger, averaging twenty-three years of age. Many of these Nisei were draftees or volunteers from the detention camps or from the "free" zones outside the camps. The MIS added a Chinese language division and a Korean language class in 1945. The largest demand for MIS personnel came after the defeat of Germany in Europe in May 1945, as the war against Japan now became the central focus of United States military efforts. Once Japan surrendered on August 15, 1945, officials revised the curriculum of the language school and civil affairs rather than military courses centered studies for those linguists needed in the United States occupation of Japan. At its peak in early 1946, the MISLS had 160 instructors and 3,000 students studying in more than 125 classrooms. [10]

The twenty-first and final commencement at Fort Snelling in June 1946 featured the graduation of 307 students, bringing the total number of MISLS graduates to more than 6,000. What began as an experimental military intelligence language-training program launched on a budget of $2,000 eventually became the forerunner of an established Defense Department language institute for thousands of linguists who served American interests throughout the world.

Preservation Efforts

Currently, there are a number of efforts underway to preserve the remaining structures of the language school and memorialize the efforts of the men of the MIS. In 1991, on the 50th anniversary of the MIS, the plight of Building 640, the site of the Military Intelligence Service Language School came to the attention of the National Japanese American Historical Society (NJAHS) by the MIS Association of NorCal. Since that time, NJAHS has advocated to preserve the building and the history of the Japanese Americans at the Presidio of San Francisco by developing it into the Military Intelligence Service Historic Learning Center.

In Minnesota, there is presently little left of Camp Savage except for one building currently being used by the Minnesota Department of Transportation Highway Department. The land adjacent to the building has been returned to the City and is being used as a training facility for the Savage Police Department's K-9 unit. A historical marker erected in 1993 identifies the site. Currently, Fort Snelling has been transformed into a historical park although evidence of the MISLS that once was located there remains unclear.

See also Military Intelligence Service

For More Information

Battad, Gwen. "Masao 'Harold' Onishi: Former MIS Instructor Shares Memories." The Hawaii Herald 14, 13 (July 2, 1993): A-16.

Central Intelligence Agency. "Nisei Linguists: Japanese Americans in the Military Intelligence Service During World War II." Last modified January 7, 2009. https://www.cia.gov/resources/csi/studies-in-intelligence/volume-52-no-4/nisei-linguists-japanese-americans-in-the-military-intelligence-service-during-world-war-ii/

City of Savage, Minnesota. "World War II Camp Savage." https://www.cityofsavage.com/our-city/about-savage/history#ad-image-1 .

The Historical Marker Database. "Camp Savage." Last modified May 5, 2011. http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=41673 .

Hiura, Arnold T. "John Alfred Burden: Plantation Doctor Pioneered MIS Efforts in the Pacific and Asia." The Hawaii Herald 14, 13 (July 2, 1993): A-14.

Go for Broke National Education Center. "School and Training Camps." https://goforbroke.org/military-intelligence-service/

Ichinokuchi, Tad and Daniel Aiso, eds. John Aiso and the M.I.S.: Japanese-American Soldiers in the Military Intelligence Service, World War II . Los Angeles: The Club, 1988.

Ishimaru, Stone S. Military Intelligence Service Language School, U.S. Army, Fort Snelling, Minnesota . Los Angeles: Tec Com Production, 1991.

Kikuchi, Yuki. The Pacific War of the Nisei in Hawaii . Translated by Yoko Hayashi Horiuchi. Pearl City, Hawaii: n.p., 1999.

Minnesota Historical Society. "Historic Fort Snelling: History." https://www.mnhs.org/fortsnelling

Minnesota Historical Society. "History Topics: Military Intelligence Service Language School at Fort Snelling." http://www.mnhs.org/library/tips/history_topics/120language_school.html .

MIS Historical Committee. The Nisei Intelligence War Against Japan . Honolulu: n.p., 199?.

MISLS Album, 1946 . Nashville: Battery Press, 1946.

National Japanese American Historical Society. "Building 640 Communique: Information Source for the Military Intelligence Service Historic Learning Center." https://www.njahs.org/building-640

Oguro, Richard S. Senpai Gumi . Honolulu: n.p., 1982?.

The Pacific War and Peace: Americans of Japanese Ancestry in Military Intelligence Service 1941 to 1952 . San Francisco: Military Intelligence Service Association of Northern California and the National Japanese American Historical Society, 1991.

A Tradition of Honor . DVD. Produced by Craig Yahata and David Yoneshige. Go For Broke Educational Foundation in Association with Hanashi Oral History Program. 2003.

"The Unsung Heroes." The Hawaii Herald 2, 21 (November 6, 1981): A-2.

Footnotes

- ↑ Research for this article was supported by a grant from the Hawai‘i Council for the Humanities .

- ↑ According to Brigadier General John Weckerling, who was the co-founder of the Military Intelligence Service Language School (MISLS) at the Presidio, "The only known source of procurement of Japanese linguists before the war were: (a) the small group of officers who had studied the Japanese language in Japan, many of whom had either been retired, incapacitated or were beyond the age and rank of interpreters, and (b) a negligible number of U.S. citizens, missionaries, businessmen and others, qualified in Japanese." Richard S. Oguro, Senpai Gumi (Honolulu: n.p., 1982?), 41.

- ↑ MISLS Album, 1946 (Nashville: Battery Press, 1946), 8.

- ↑ The Nisei Intelligence War Against Japan , comp. MIS Historical Committee (Honolulu: n.p., 199?), 2.

- ↑ The Pacific War and Peace: Americans of Japanese Ancestry in Military Intelligence Service 1941 to 1952 (San Francisco: Military Intelligence Service Association of Northern California and the National Japanese American Historical Society, 1991), 2.

- ↑ Stone S. Ishimaru, Military Intelligence Service Language School, U.S. Army, Fort Snelling, Minnesota (Los Angeles: Tec Com Production, 1991), 6.

- ↑ Arnold T. Hiura, "John Alfred Burden: Plantation Doctor Pioneered MIS Efforts in the Pacific and Asia," The Hawaii Herald 14, 13 (July 2, 1993): A-14.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Yuki Kikuchi, The Pacific War of the Nisei in Hawaii , trans. Yoko Hayashi Horiuchi (Pearl City, Hawaii: n.p., 1999), 79.

- ↑ MIS Historical Committee, The Nisei Intelligence War Against Japan (Honolulu: n.p., 199?), 5.

Last updated April 17, 2024, 4:26 a.m..

Media

Media