Salinas (detention facility)

| US Gov Name | Salinas Assembly Center, California |

|---|---|

| Facility Type | Temporary Assembly Center |

| Administrative Agency | Wartime Civil Control Administration |

| Location | Salinas, California (36.6667 lat, -121.6500 lng) |

| Date Opened | April 27, 1942 |

| Date Closed | July 4, 1942 |

| Population Description | Held people from the Monterey Bay area of California. |

| General Description | Located at the north end of the town of Salinas, California. |

| Peak Population | 3,594 (1942-06-23) |

| Exit Destination | Poston and Tule Lake |

| National Park Service Info | |

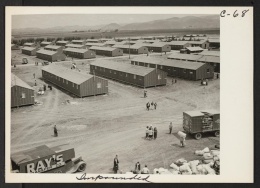

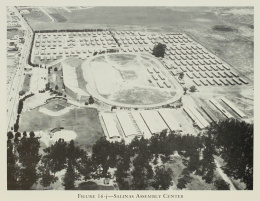

The Salinas Assembly Center was located at the Salinas Race Track and Fair Grounds at the north end of Salinas. The third least populous of the " assembly centers " with a peak population of 3,594, its inmate population consisted almost entirely of Japanese Americans from nearby agricultural communities including Watsonville, Salinas, and Gilroy. Despite being open for a short sixty-nine days (April 27 to July 4, 1942), it had an active community government under camp manager E. A. Rose and many recreational and educational programs. Nearly the entire population of the camp was transferred on to Poston between June 28 and July 4, 1942.

Site History/Layout/Facilities

The Salinas Race Track and Fair Grounds was located about five miles north of downtown Salinas. Upon acquisition of the site, the Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA) contracted the Dale Brothers and Doudell Construction Company to build the camp. The approximately 142 buildings were built adjacent to, but outside of the racetrack. Water for the camp came from both the Salinas municipal supply and a well on the rodeo grounds; both sources passed muster with the County Health Department. The sewers were discharged into the Salinas sewer system. The camp was ready for induction by April 27, 1942. [1]

In contrast to other "assembly centers" and the later War Relocation Authority (WRA) administered concentration camps, the barracks at Salinas were not grouped into blocks or wards, but were simply numbered consecutively from 1 to 142. The camp address was simply the barrack number and the unit number within the barrack, e.g. "Building 128–C." About 130 of the 20 x 100 buildings were used as living quarters, with the rest used as administration offices (4), an infirmary (3), and for various recreational purposes (two churches, a library, and two recreation halls). [2]

The newly constructed residential barracks anticipated the WRA barracks in that they were long wooden buildings that were subdivided into smaller living quarters, typically five 20 x 20 foot units. The dividers were plywood panels that were eight feet high, leaving a gap at the top. Seven of the barracks were designated for single adults (five for men, two for women) and were not partitioned. The floors were made of wood and elevated twelve to eighteen inches above the ground. Among the issues with the barracks cited by both outside inspectors and inmate committees were the lack of screens on windows and doors and cracks in the barracks floors which allowed dust in and caused "the rooms to be drafty and cold." [3]

The latrines at Salinas ranged from among the worst to among the best among assembly centers. The initial latrines were pit toilets, "of the earth privy type, consisting of two wooden bench-type risers, each with four or more seats, placed back to back over a pit," as described in a May 12 U.S. Public Health Service inspection report. This report noted numerous problems with this set up. "The risers, being made of wood, are not waterproof," the report read. "Some of them are lined in front with roofing paper, but this was not done in all cases, and as a result the wood is becoming soaked with urine." Urinal troughs in the men's latrine drained to soakage pits outside the latrine building. "Because of the dense, clayey character of the soil it is poorly suited to disposal of sewage or waste water by absorption. Difficulty has already been experienced with operation of the soakage pits at two latrines and nuisance conditions have resulted." The latrines also had dirt floors. A WRA commissioned report on May 2 by journalist Milton Silverman described the latrines in a similar fashion, calling them "dirty, poorly-ventilated and dark." [4]

Within a week of this report, work had started to replace the pit toilets with flush toilets. To be completed in fifteen days, the resulting latrine system would have sixteen new buildings each with twelve flush toilets plus urinals for the men. The June 9 report to the WCCA office reported that the "sanitary sewage system is practically completed and toilet facilities are in use." With perhaps some hyperbole, the report continues, "[t]his is such an improvement over the old pit-type toilets that we feel we could put up with most anything else at the present time." [5]

The eight bathhouses (four each for men and women) were 20 x 28 foot buildings that each had sixteen shower heads and hot and cold water, along with galvanized wash troughs on the outdoor walls. In Treadmill , a novel written at Poston, Hiroshi Nakamura describes the wash basins at Salinas as having eaves that extended "just far enough to make it miserable for the washers" when it rained, as water dripped on them. The U.S. Public Health Service Report noted that the shower valves were too high (seven feet) for many of the inmates to reach; the protagonist in Treadmill takes to accompanying shorter friends to the shower to turn on the water for them. Silverman reported that the showers were "so constructed that only a tall Caucasian—that is, no ordinary short Japanese—could reach the overhead faucets." Latrines and showers were initially unpartitioned, though Camp Manager E. A. Rose promised that the women's at least would subsequently be partitioned at the first Board of Advisors meeting on May 20. Nakamura also writes that the "lone laundry at the south end of the camp was inaccessible to twenty-nine hundred of the three thousand evacuees." [6]

There were also eight "H" shaped mess buildings (with the kitchen in the middle), each designed to serve about 500 people. For various reasons, the food served in the mess halls became perhaps the biggest problem for many of the inmates at Salinas. Rose's reports to the WCCA noted "the lack of properly trained cooks," and asks about the possibility of transferring experienced cooks from other assembly centers. Lines were also a problem, as at many of the other camps. There were also labor issues in the mess halls, with many kitchen workers quitting because of the long and irregular hours, the lack of staffing and equipment, and disputes with Chief Steward Louis V. Leval, who supervised the staff. [7]

But the biggest problem was the quality and quantity of the food itself. In his May 27 narrative report, Rose wrote that "the head of our Mess and Lodging Division had been misinformed as to the amount of money that could be spent for food. The average food cost since the center has been in operation is about 33¢ per day per person, and this is entirely insufficient to maintain the health and well-being of the residents." In his June 2 report, he wrote that there were

numerous complaints and my own investigation satisfied me that the complaints were justified. The main course of one meal served recently consisted of a codfish concoction using 12 pounds to feed 600 people. Jesus Christ used 5 loaves of bread and 2 fish to feed the multitude but he was able to perform a miracle which we cannot. I have requested the supervisor of the Mess and Lodging to order food in sufficient quantities and of the necessary varieties to prepare and serve a well-balanced meal at all times, and reports lately have indicated a great deal of improvement in the mess situation.

Minutes from a June 10 Board of Advisors meeting notes that the "[q]uality and quantity [was] much improved." No further discussion of the food situation is noted. [8]

Camp Population

Nearly all of the camp population came from areas near Salinas. The roughly 2,700 Japanese Americans from Monterey and Santa Cruz Counties arrived between April 27 and April 30, 1942. After a gap of nearly three weeks, a second group of over 800 from San Benito County and the southern portion of Santa Clara County (that included the towns of Gilroy and Hollister) arrived between May 18 and 20. The peak population of the camp was 3,594, on June 23. The population was largely rural and included many lettuce farmers from Watsonville and Salinas, an area known as the "Lettuce Bowl of America." This group had faced harsh anti-Japanese agitation from competitors. There were also many fishermen from Monterey and other coastal areas. [9]

| Exclusion Order # | Deadline | Location | Number |

| 15 | April 30 | Monterey County: Salinas, Castroville | 1,578 |

| 16 | April 30 | Santa Cruz County: Watsonville | 1,160 |

| 77 | May 21 | Santa Clara and San Benito Counties: Hollister, Gilroy | 835 |

Source: John L. Dewitt, Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 (Washington D.C.: U.S. Army, Western Defense Command), 363–66. Exclusion orders with fewer than twenty inductees not listed. Deadline dates come from the actual exclusion order posters, which can be found in The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement: A Digital Archive, Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley, http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_b016b01_0001_1.pdf and http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_b016b01_0001_2.pdf .

| Arrival Date | Number |

| April 27 | 476 |

| April 29 | 1,317 |

| April 30 | 964 |

| May 3 | 9 |

| May 18 | 2 |

| May 20 | 391 |

| May 21 | 409 |

Source: "Report of the Salinas Assembly Center, Rodeo Grounds, Salinas, California," May 26, 1942, p. 2, 1.173, Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno.

As was true at many of the other camps, many of the inmate leaders were Nisei professionals who were members of the

Japanese American Citizens League

(JACL). For example, Kenzo Yoshida, the director of indoor recreation was the president of Salinas JACL; Dr. George Hiura, treasurer of the recreation committee and leader of the "Movies" group, was a Sebastopol dentist and former president of the Sonoma County JACL.

[10]

According to the DeWitt report , there were thirteen births and two deaths. One of the deaths was of a 69-year-old man due to a heart attack. The other was a thirteen-year-old boy, Noriyuki Hashimoto, who died of an injury suffered in a camp baseball game. [11]

Barely a month after the last inmates had arrived, the transfer to Poston began. The transfer took place in seven movements, from June 28 to July 4, with each movement consisting of about 500. The first group to go were barracks 125 to 142. [12]

| Departure Date | Camp | Number |

| June 28 | Poston | 483 |

| June 29 | Poston | 482 |

| June 30 | Poston | 499 |

| July 1 | Poston | 451 |

| July 2 | Poston | 451 |

| July 3 | Poston | 517 |

| July 3 | Tule Lake | 105 |

| July 4 | Poston | 592 |

Source: John L. Dewitt, Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 (Washington D.C.: U.S. Army, Western Defense Command), 282–84.

A small number of inmates who had health issues—about 100—were sent to

Tule Lake

along with their families. Helen Nakamura, for instance, was among those sent there with her family because one of her sisters had tuberculosis.

[13]

Staffing

The center manager of Salinas for the duration of its existence was E. A. Rose. Historian Brian Hayashi writes that Rose "allowed liberal camp government, allowing the 18 member council and advisory board—which was largely made up of professionals—to run the twice daily roll calls, to allow unescorted visits to the outside, and to hold sumo tournaments." [14]

The majority of the staff came from the ranks of the Works Progress Administration, including all of the division heads. Another 30% were hired locally.

Other key staff members:

Superintendent of Works Division: Paul H. Baker, from Concord, California

Supervisor of Mess and Lodging: John V. Kirsch, from Sellack, Washington; he had been the WPA manager at the Grand Coulee Dam

Supervisor of Supplies: William F. Taylor, from Roswell, New Mexico

Chief of Personnel: Gustavus Scheneider, from Carmel, California

Fire Chief: Earl C. Pierson, from Salinas

Chef Steward: Louis V. Laval, from Los Angeles

Supervisor of Service Division: Lindsley Luddeke

Store Executive: Bert A. Southard

Aside from Rose, Baker drew the top salary at $3,600 per year, with the rest between $2,400 and $3,300. [15]

Institutions/Camp Life

Community Government

Camp Manager Rose appointed a fourteen-member Center Council who met for the first time on May 18. The council included one representative for every seven or eight barracks or around two hundred people. The initial group was as follows:

Mr. I. Yoshitomi, representing Buildings 8–14

Mr. E. Tatsumi, 15–20

Dr. H. F. Ito, 21–27

Dr. M. Takeshita, 28–35

Mr. Z. Tachibana, 36–42

Mr. Kenzo Yoshida, 43–50

Mr. John Urabe, 51–57

Mr. Kenichi Takemoto, 58–64

Mr. W. Shirachi, 72–78

Dr. H. Y. Kita, 79–86

Mr. Y. Ichikawa, 111–18

Mr. C. Iwamoto, 119–26

Mr. Sumio Nishi, 127–34

Mr. Shizuo Ikeda, 135–42

The group, which was all male, included Issei and Nisei and was a mixture of farmers and business owners with professionals such as doctors, dentists, and optometrists. At their initial meeting, the group elected Dr. Harry Y. Kita, a Nisei dentist from Salinas, as chairman. They also elected a five-man Board of Advisors that included Urabe, Yoshida, Iwamoto, and Ito, all of whom were Nisei except for Ito, an Issei dentist from Watsonville. Kita and Urabe, a Salinas businessman, were both founding members of the Salinas Valley JACL. After the later group of inmates from Hollister and Gilroy arrived in late May, Rose appointed four more council members to represent that group:

Mr. Frank Yamashichi, 1–7

Mr. Takeichi Kodani, 65–71

Mr. Shuichi Nishida, 95–102

Mr. Tsutomu Awaya, 103–10

[Note that buildings 87–94 were used for administration and for the infirmary.]

The council met weekly on Monday nights, while the smaller advisors group met with Rose on Wednesday nights. As with other forms of concentration camp "self" governance, neither group had a lot of power, but did have the ability to convey complaints and other issues to Rose and the staff. The council also appointed inmate committees that took charge of such areas as recreation and education. In Treadmill , Nakamura writes that the council "was a sore point with the Issei," since it was composed of practically the same group who before evacuation set themselves up as spokesmen for all Japanese in the Valley," echoing complaints about councils at Puyallup , Sacramento , and other assembly centers. [16]

Education

As was the case with most assembly centers, there was little in the way of formal educational programs provided by the government. The WCCA largely didn't provide for education, given the short lifespan of the camps and the fact that much of that lifespan coincided with the summer vacation months. Nonetheless, Salinas had a fairly ambitious inmate-run program relative to other camps with such short lifespans.

The Center Council tapped three volunteers to head the educational program: Helen Aihara (later Kitaji) of Sunnyvale, a graduate of San Jose State College and Stanford who had taught in San Jose schools; Katherine Watanabe of Santa Cruz, another San Jose State graduate who also attended Chounard Art Institute for three years; and Dr. George Hiura, a Sebastopol dentist. Their efforts would be hampered by both a lack of qualified personnel and of supplies and equipment. The May 26 report to the Secretary of War noted a "lack of qualified instructors, there being only two certified teachers available in camp," and a "lack of basic equipment, tables, chairs, etc." [17]

Nonetheless, the group first set up a nursery school led by Aihara that began on June 1 with two sections of thirty children each that met three times a week. There would eventually be four nursery school sections and later four elementary school groups. A June 16 report noted that "lack of standard equipment has resulted in the manufacture of some ingenious furniture and other equipment." There was less for older kids, with just art classes offered for the middle and high school aged youth. There were also adult "Americanization" classes as well a home nursing and craft classes. In an effort to alleviate the teacher shortage, the group also set up teacher training classes. All of these classes met in either laundry buildings, kitchens, or the library. [18]

As at other camps, there were special graduation ceremonies for graduating high school seniors. Separate such ceremonies were held for graduates of Salinas, Watsonville, and Hollister High Schools. Personnel from those schools came to the camp to take part in the ceremonies and pass out the diplomas. [19]

Medical Facilities

The camp infirmary and clinic was located in three barracks, Buildings #92, 93, and 94. As at other assembly centers, the infirmary suffered from a lack of personnel, supplies, and equipment. A May 2 report notes that there was only one R.N. in the camp, which created a situation that "forced us to assign inexperienced girls to the infirmary staff to wait upon patients." A May 26 report added, "As to equipment and supplies, they are not sufficient, especially in the dental department. Dental chairs are not available yet." [20]

Nonetheless, the inmate medical staff by May 26 came to include three doctors, a head nurse, two graduate nurses, two student nurses, twenty nurse's aides, two dentists, and two pharmacists. The report added that "Emergency operations and obstetrics cases are sent to the Monterey County Hospital...." [21]

Library

As at many camps, the library at Salinas became a popular gathering place. Camp manager Rose worked with Ellen B. Frank, the Monterey County Free Library librarian, to establish the camp library as a branch of the Monterey County system, which was eventually approved by the County Board of Supervisors on May 18. Located in Building #7, it was staffed by Fusako Kodani (later Onoye) of Monterey. Though she had no formal library training beyond high school, she had worked for artist Chiura Obata and had been the secretary of the Monterey JACL chapter. She was assisted by ten volunteers. [22]

The library took up five connected rooms in the barracks that included reading rooms for adults and for children, as well as a seminar room. Thanks to the affiliation with the county library, a rotating supply of about 450 books from the county were available as well as an additional 200 donated books by the end of May. Some 500 people a day visited the library and its average circulation was 200 a day. The library later hosted an art exhibition that featured over forty paintings, most of them done by camp artists. The May 26 report to the Secretary of War reported that library facilities "are taxed to the utmost.... Observation has shown that all seating arrangements are taxed to capacity." It added that the library provided a "very visible uplift on center morale" and that "this service will be one of the most outstanding we have offered in this center." [23]

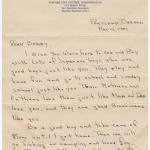

Newspaper

The Village Crier —so named after an unnamed first edition on May 11—put out eight weekly issues, with the last appearing on June 28. The Center Council recommended twenty-seven-year-old Yoshiye Takata of Watsonville to be the editor, and she remained in that position throughout. Other staffers included Yoshiye's sister Kikuye Takata as contributing editor and social editor, Hiroshi Wada as sports editor, circulation staffers Paul Yamaguchi and Mickey Fujikawa, and mimeographer Pauline Yamaguchi. The newspaper office was 89-E. [24]

Religion

Both Buddhist and Christian churches held services at Salinas, the former in Building #72, the latter in #53. Both offered Sunday services and Sunday schools. The Buddhist minister was Rev. Yoshio Iwanaga; the Christian ministers were Rev. K. Takeda and Rev. K. Noji. There were about 1,500 members of the Buddhist church and about 500 of the Christian. [25]

Recreation

The Center Council appointed a group of inmate leaders to oversee recreational programs at Salinas. This group included overall chair Kenzo Yoshida, co-director Yoneo Goto, secretary Yoshiye Takata and treasurer Dr. George Hiura. Yoshida also coordinated indoor recreation, while John Urabe coordinated outdoor recreation. [26]

Chief among the outdoor programs were sumo and softball. By June 9, there were twenty-two adult softball teams with about 300 players that drew large crowds to their games. A June sumo tournament had seventy-five participants and 1,500 spectators. In mid-June, a new baseball diamond, volleyball, badminton, croquet and basketball courts were built. Horseshoes, touchball, speedball, and netball games were also popular. [27]

On the indoor side, musical programs may have been most popular. Senior and junior orchestras and a dance band formed along with boys' and girls' choruses; all seemed to practice in Building #95. Bridge and karuta clubs were also popular. As at other camps, programs featuring camp talent were popular, with much of the camp population attending weekly Sunday programs. [28]

Store/Canteen

The camp store was located near the Post Office between Buildings #79 and 80. Bert Southard managed the 1,400 square foot store which was staffed by twelve inmates. Among the most popular items sold were soda, candy, and cigarettes. Inmate complaints about the store included the high pricing relative to outside stores and its unhealthy offerings. Rose seemed to agree with this, telling the Center Council that the "'stuff' people are buying is not good for them. A request for items that people use in everyday life such as soap, shaving cream, razor blades, cosmetics, etc. has been sent in." [29]

Visitors

A "Reception Hall" where inmates would be allowed to greet visitors opened in early June. [30]

Other

As at other assembly centers, inmates worked a 44 hour week for wages on an $8/$12/$16 per month scale. [31]

The police and fire department were located in Building #89. The fire station included a Caucasian chief and two Caucasian assistant chiefs, along with fifteen inmate firemen. One of white chiefs was on duty at all times. [32]

An Information Center was also located in Building #89. [33]

The Post Office began operations on May 20. Located in a 9 x 20 room in the store building, it was staffed by a chief mail orderly, three assistant orderlies and eight mail carriers who delivered mail to inmates daily. It handled 1,000 to 1,500 first class items, 100 to 200 2nd class, and 1,000 4th class per day. [34]

Chronology

April 6

Center Manager E.A. Rose arrives at the Salinas Assembly Center.

April 27

Arrival of the first inmates, 414 from Monterey County and 63 from Santa Cruz County, a total of 477. One of the arrivals, Kazuto Miyahara, was taken into custody by the FBI that afternoon, leaving the total number in the camp at 476.

May 1

Gen.

John DeWitt

,

Karl Bendetsen

and others visit the camp for an inspection.

May 10

Center Store opens for business.

May 11

First issue of unnamed newspaper appears.

May 18

First meeting of the Center Council, a group of fourteen appointed by Rose. The group elects a chairman and a five person Board of Advisors.

June 1

Nursery school to begin "in the laundry unit," open to children ages 3 to 5.

Graduation ceremony for forty-two seniors at Salinas High in the reception building. Salinas High School principal Nelson B. Sewell spoke and passed out the diplomas. A reception and dance followed.

June 7

Sumo ring dedicated in front of Recreation Building #48.

June 17

First pay checks for center workers distributed.

June 19

Graduation ceremony for thirty seniors at Watsonville High School takes place in Building 72. School officials, including principal Thomas S. MacQuiddy and dean of girls Louise Worthington take part and pass out the diplomas.

June 28

Last issue of the

Village Crier

appears.

The first group leaves for Poston.

July 4

The last group leaves for Poston. An inmate work crew remained in the center for a few days to clean up.

Quotes

"The sewage overflowed from the girls' latrine. It came up through the floor and formed puddles in front of both doors. To those who had to teeter across them, the lack of wider planks to lay across the puddles of sewage was more important than the lack of rubber on tires. The inefficiency of the local administration and the self-interest and petty bickering of the Evacuee Council were of paramount concern."

From

Treadmill

by Hiroshi Nakamura, ca. 1945

[35]

"Many complaints have been received concerning the operation of the mess halls and the quality and quantity of the food served. Apparently the head of our Mess and Lodging Division had been misinformed as to the amount of money that could be spent for food. The average food cost since the center has been in operation is about 33¢ per day per person, and this is entirely insufficient to maintain the health and well-being of the residents."

Camp manager's report, May 27, 1942

[36]

Aftermath

After the detention facility closed, the site was used as satellite troop housing for Fort Ord. The site now houses the California Rodeo Grounds, a small neighborhood park, and the Salinas Community Center. [37]

Salinas Assembly Center was one of the twelve California temporary detention centers to share California Historical Landmark #934, so named in 1980. Starting at the end of 1982, a Kinenhi (Monument) Committee that included members of five local JACL chapters formed and worked to build a historical marker and small Japanese garden at the site of the camp. The marker and garden, located in Sherwood Park at 940 North Main Street, were dedicated at a Day of Remembrance (DoR) on February 19, 1984. Vandals defaced the marker and garden three months later, causing damage estimated at $35,000. It was later restored by the local community. [38]

A new plaque was dedicated in 2010 identifying the site as the "Day of Remembrance Memorial Garden." Also in that year, the site was named a Salinas Literary Landmark. The site continues to be used for DoRs to the present day. [39]

Notable Alumni

For More Information

Burton, Jeffery F., Mary M. Farrell, Florence B. Lord, and Richard W. Lord. Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites . Western Archeological and Conservation Center, National Park Service, 1999, 2000. Foreword by Tetsuden Kashima. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002. The Salinas section of 2000 version accessible online at http://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/anthropology74/ce16j.htm .

Lydon, Sandy. The Japanese in the Monterey Bay Area: A Brief History . Capitola, Calif.: Capitola Book Company, 1997.

Nakamura, Hiroshi. Treadmill: A Documentary Novel . Oakville, Ontario: Mosaic Press, 1996. [The only known novel written in camp by an incarcerated Japanese American includes three chapters set in the Salinas Assembly Center.]

Salinas Assembly Center video. Japanese American Memorial Pilgrimages, 2018.

Footnotes

- ↑ Note: This article draws heavily on records of the Wartime Civil Control Administration on microfilm at the San Bruno, California, branch of the National Archives and Records Administration. All of the cited records come the Salinas Center Manager's File in the Administrative Records section. Categories of materials (possibly corresponding to the physical folders they were housed in) are given numbers in the format "1.xxx." Records below will be cited by that number and the microfilm reel on which they are found. Brian Masaru Hayashi, Democratizing the Enemy: The Japanese American Internment (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004), 88; Village Crier , May 30, 1942, 1; Jeffrey F. Burton, et al., Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002), 368–69; Memo, Phillip J. Caffey, assistant sanitary engineer, U.S. Public Health Service, to Senior Surgeon W. T. Harrison, director, District No. 5, May 12, 1942, p. 1, 1.127 ("Health & Sanitation"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno; "Report of the Salinas Assembly Center, Rodeo Grounds, Salinas, California," May 26, 1942, p. 1, 1.173, Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Village Crier , May 30, 1942, 1; "Report of the Salinas Assembly Center," May 26, 1942, 33.

- ↑ Memo, Caffey to Harrison, 2; Narrative Report #2, Apr. 29, 1942, 1.152 ("Narrative Reports to S.F. Office"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno; Minutes, Meeting of the Board of Advisors, Salinas Assembly Center, May 20, 1942, 1.110 ("Board of Advisors"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno; "Report of the Salinas Assembly Center," May 26, 1942, 34.

- ↑ Memo, Caffey to Harrison, 1–4; Milton Silverman, "Assembly Centers: Salinas," p. 4, Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Records, Bancroft Library, University of California at Berkeley, BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder B9.01, https://oac.cdlib.org/ark:/28722/bk0013c8w5p/?brand=oac4 .

- ↑ Letter, Kenneth C. Sheriff, M.D., Monterey County Health Officer, to C. G. Gillespie, chief, Bureau of Sanitary Engineering, State Department of Public Health, May 19, 1942, 1.127 ("Health & Sanitation"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno; Narrative Report #9, June 9, 1942, 1.152 ("Narrative Reports to S.F. Office"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ "Report of the Salinas Assembly Center," May 26, 1942, 33; Hiroshi Nakamura, Treadmill: A Documentary Novel (Oakville, Ontario: Mosaic Press, 1996), 46, 52, 56; Memo, Caffey to Harrison, 2; Silverman, "Assembly Centers: Salinas," 4-5; Minutes, Meeting of the Board of Advisors, Salinas Assembly Center, May 20, 1942.

- ↑ Memo, Caffey to Harrison, 2; Narrative Reports #3 and 6, May 2 and 20, 1942, 1.152 ("Narrative Reports to S.F. Office"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno; Notes on Meeting of the Board of Advisors, Salinas Assembly Center, May 26, 1942, 1.110 ("Board of Advisors"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno; Minutes, Salinas Assembly Center Council, Organizational Meeting, May 18, 1942, 1.113 ("Center Council"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Narrative Reports #7 and 8, May 27 and June 2, 1942, 1.152 ("Narrative Reports to S.F. Office"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno; Minutes, Meeting of the Board of Advisors, Salinas Assembly Center, June 10, 1942, 1.110 ("Board of Advisors"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ John L. Dewitt, Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 (Washington D.C.: U.S. Army, Western Defense Command), 363–66; "Report of the Salinas Assembly Center," May 26, 1942, 2; Silverman, "Assembly Centers: Salinas," 1–4.

- ↑ "Personnel for Division of Indoor Recreation," 1.169 ("Recreation"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno; Indoor Recreation Committee Report, May 7, 1942, 1.169 ("Recreation"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Dewitt, Final Report , 202; Pacific Citizen , June 4, 1942, 7; Mas Hashimoto interview by Tom Ikeda, Segment 17, Watsonville, California, July 30, 2008, Watsonville - Santa Cruz JACL Collection, Densho Digital Repository, https://ddr.densho.org/media/ddr-densho-1015/ddr-densho-1015-7-transcript-e30c62a34a.htm

- ↑ Dewitt, Final Report , 282–84; Narrative Report #11, June 23, 1942, Section 1.152 ("Narrative Reports to S.F. Office"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Dewitt, Final Report , 282–84; Helen Miyako Nakamura, interview by Charles Kikuchi, p. 40, The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement: A Digital Archive, Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley, BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder T1.932, http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_box279t01_0932.pdf .

- ↑ Hayashi, Democratizing the Enemy , 99.

- ↑ "Report of the Salinas Assembly Center," May 26, 1942, 1; " Status of Appointive and Currently Assigned Personnel at Salinas Assembly Center," 1.137 ("Instructions, Received"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno; Letter, R. L. Nicholson, chief, Reception Centers Division, Wartime Civil Control Administration, to E. A. Rose, Apr. 11, 1942, 1.163 ("Personnel"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno; Village Crier , May 23, 1942, 1.

- ↑ Sources for this section include "Salinas Assembly Center Council, June 1, 1942," 1.113 ("Center Council") Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno; Narrative Reports #6 and 11, May 20 and June 23, 1942, Section 1.152 ("Narrative Reports to S.F. Office"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno; Minutes, Meeting of the Board of Advisors, Salinas Assembly Center, May 20, 1942, 1.110 ("Board of Advisors"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno; Mae Sakasegawa, ed., The Issei of the Salinas Valley: Japanese Pioneer Families (Salinas Valley JACL Seniors, 2010), 103, 273–74; and Village Crier , May 30, 1942, 1 and June 20, 1942, 2; Nakamura, Treadmill , 59.

- ↑ "Personnel for Division of Indoor Recreation," 1.169 ("Recreation"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno; "Report of the Salinas Assembly Center," May 26, 1942, 13–14.

- ↑ Village Crier , May 30, 2, June 6, 1, and June 13, 2; Education report, June 16, 1942, 1.177 ("Service Division"); "Report of the Salinas Assembly Center," May 26, 1942, 13–17.

- ↑ Report of Week Ending June 6, 1942, 1.177 ("Service Division"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno; Village Crier , June 20, 3.

- ↑ Bulletin #1, Administrative, Salinas Assembly Center, May 8, 1942, 1.113 ("Center Council"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno; Narrative Report #3, May 2, 1942, Section 1.152 ("Narrative Reports to S.F. Office"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno; "Report of the Salinas Assembly Center," May 26, 1942, 12.

- ↑ "Report of the Salinas Assembly Center," May 26, 1942, 11–12.

- ↑ Ellen B. Frank, librarian, Monterey County Free Library, to E. A. Rose, May 19, 1942, 1.141 ("Library, Service Division"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno; Village Crier, May 30, 3; Personnel for Division of Indoor Recreation, 1.169 ("Recreation—Service Division"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno; "Report of the Salinas Assembly Center," May 26, 1942, 30.

- ↑ "Report of the Salinas Assembly Center," May 26, 1942, 30–31; Narrative Reports #8 and 9, June 2 and 9, 1942, Section 1.152 ("Narrative Reports to S.F. Office"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno; Library report, June 16, 1942, 1.177 ("Service Division"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Minutes, Meeting of the Board of Advisors, Salinas Assembly Center, June 3, 1942, 1.110 ("Board of Advisors"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno; Village Crier, June 20, 1941, 5.

- ↑ "Report of the Salinas Assembly Center," May 26, 1942, 20–21; Village Crier , May 19, 1942, 1.

- ↑ Village Crier , May 11, 1942, 1; Minutes, Recreational Committee Meeting, May 7, 1942, 1.169 ("Recreation—Service Division"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Report of Week Ending June 6, 1942, 1.177 ("Service Division"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno; Narrative Report #9, June 9, 1942, Section 1.152 ("Narrative Reports to S.F. Office"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Narrative Report #8, June 2, 1942, Section 1.152 ("Narrative Reports to S.F. Office"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno; Village Crier, May 30, 1942, 1; Report of Week Ending June 6, 1942, 1.177 ("Service Division"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno; Camp Entertainment report, June 16, 1942, 1.177 ("Service Division"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Village Crier , June 6, 1942, 2; "Report of the Salinas Assembly Center," May 26, 1942, 21–23, 45–46; Minutes, Meeting of the Board of Advisors, Salinas Assembly Center, May 20, 1942, 1.110 ("Board of Advisors") Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno; Minutes, Salinas Assembly Center Council, Organizational Meeting, May 18, 1942, 1.113 ("Center Council"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Village Crier , June 6, 1942, 1.

- ↑ Minutes, Salinas Assembly Center Council, Organizational Meeting, May 18, 1942, 1.113 ("Center Council"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Village Crier , May 19, 1942, 1; Minutes, Salinas Assembly Center Council, Organizational Meeting, May 20, 1942, 1.113 ("Center Council"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ "Report of the Salinas Assembly Center," May 26, 1942, 23–25.

- ↑ Minutes, Salinas Assembly Center Council, Organizational Meeting, May 20, 1942, 1.113 ("Center Council"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno; "Report of the Salinas Assembly Center," May 26, 1942, 27–29.

- ↑ Nakamura, Treadmill , 59.

- ↑ Narrative Report #7, May 27, 1942, 1.152 ("Narrative Reports to S.F. Office"), Reel 21-L, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Burton, et al., Confinement and Ethnicity , 368–69.

- ↑ Barbara Wyatt, ed., Japanese Americans in World War II: National Historic Landmarks Theme Study (Washington, D.C.: National Historic Landmarks Program, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 2012), 120; Rafu Shimpo , Feb. 15, 1984, 1 and June 1, 1984, 1; Fred Oshima, "Salinas Valley JACL Report, 1989," Pacific Citizen , Jan. 26, 1990, 2.

- ↑ Wyatt, ed., Japanese Americans in World War II ; Rafu Shimpo , Mar. 12, 2012, 1 and Feb. 6, 2019, 1.

Last updated Jan. 22, 2024, 10:49 a.m..

Media

Media