Stockton (detention facility)

| US Gov Name | Stockton Assembly Center, California |

|---|---|

| Facility Type | Temporary Assembly Center |

| Administrative Agency | Wartime Civil Control Administration |

| Location | Stockton, California (37.9500 lat, -121.2833 lng) |

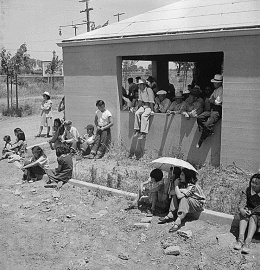

| Date Opened | May 10, 1942 |

| Date Closed | October 17, 1942 |

| Population Description | Held people from San Joaquin County, California. |

| General Description | Located at the San Joaquin County Fairgrounds in Stockton, California. |

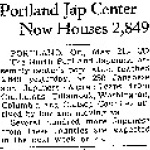

| Peak Population | 4,271 (1942-05-21) |

| National Park Service Info | |

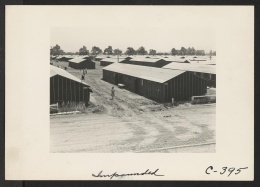

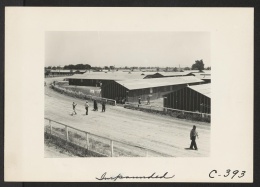

The Stockton Assembly Center was built on the site of the San Joaquin County Fairgrounds southeast of downtown Stockton. Inmates lived in newly constructed barracks located both within the fairgrounds racetrack and adjacent to it. Nearly its entire inmate population came from Stockton, Lodi and surrounding farming areas in San Joaquin County. The first advance inmate groups arrived on May 10, 1942, and the camp's peak population of 4,271 was reached just eleven days later. The camp remained in operation for over five months, making it one of the longest running of the assembly centers and resulting in a relatively more robust inmate-run educational program. Essentially the entire population of Stockton went to Rohwer , with a small number of tuberculosis patients and their families going instead to Gila River .

Site History/Layout/Facilities

The Stockton Assembly Center was built on the 110-acre site of the San Joaquin County Fairgrounds, a little over two miles southeast of downtown Stockton. A map that appears as a supplement to the first issue of the camp newspaper, the El Joaquin , shows ten blocks , seven of which were built within the racetrack and three built outside the racetrack, each with about twenty barracks. When he arrived on April 6, 1942, Camp Manager Harold Mundell wrote that the construction was about 75% complete, as 1,800 workers battled heavy rain that continued for the next three weeks. Nonetheless, in his April 30 report, he wrote that contractors had completed construction that week. However, after the arrival of the first inmates on May 10, he wrote in his May 13 report that the contractors were back doing a number of tasks, including "doubling the facilities of our showers and toilets throughout the grounds, sealing hospital wards, and installing heating for the hospital." [1]

Each barrack was 100 feet long by 20 feet wide and divided into five units, one 20 x 20 and two each 16 x 20 and 24 x 20. Residential barracks were numbered consecutively from 1 to 178. Block addresses thus took the form of block number, barrack number and unit letter, e.g. "9–169–B." Although the El Joaquin map depicts ten blocks, it appears that inmates lived only in blocks 1 to 9, with the buildings of Block 10, located south of the racetrack, apparently being used for other purposes. Given the shape of the site and the racetrack, the blocks were irregularly shaped and varied in the number of barracks they contained from seventeen to twenty-one and had inmate populations of between 450 and 500. Each block also had two bath houses, two latrines, and a mess hall. [2]

While there are several retrospective accounts of inmates being housed in horse stalls as in some of the other assembly centers, contemporaneous documents suggest that this did not occur at Stockton. The uniformity of the barracks depictions in both the El Joaquin map and in Mundell's report to the secretary of war suggest that they were newly built. Mundell's May 2 narrative report includes the following sentence: "I refer to my teletype yesterday, which states that General DeWitt did not want evacuees quartered in the stables tentatively prepared for quartering evacuees. These stables have a sand floor, and are not thoroughly clean. Consequently, our capacity is reduced by the figure furnished you yesterday in my teletype." A sanitation report by Philip J. Coffey of the U.S. Department of Public Health on May 23 does not mention horse stalls and states that "all [of the barracks] have concrete floors." An article on the August 5 issue of the El Joaquin , notes that the 8th hole of the Stockton Municipal Golf Course "runs parallel to the horse stalls at Block 10," in a story about how inmates have been able to make money by gathering and selling stray golf balls. Given that Block 10 remained unoccupied throughout suggests that it was the site of the "stables" DeWitt mentions and that while they were initially slated to house inmates, ultimately did not. While it is possible that inmates may been placed in Block 10 stables temporarily, that seems unlikely, given that Coffey's report—based on a visit on May 14, just four days after inmate began to arrive—did not mention them. But ultimately, there is no way to know for certain whether stables were used to house inmates at Stockton. [3]

Barracks, bath houses, and latrines were all built of wood, and all had concrete floors. Barrack units had windows, but no screens in either the windows or doors. Unlike many other assembly centers, real cotton mattresses were provided, along with blankets. Bath houses had eight shower heads each originally, which was later increased to sixteen; women's showers were partitioned. The latrines had eight flush toilets each—flush toilets were unusual for the smaller assembly centers—along with two urinals in the men's latrine. Coffey's reports calls the latrines "screened and well ventilated.... The only objection heard was concerning lack of partitions between toilets in women's latrines." There were four laundry rooms, each with twenty-four pairs of laundry trays and forty electrical outlets. Retrospective accounts by Jeanette Arakawa and George Omi recall the camp being surrounded by barbed wire fences and guard towers. [4]

The mess halls each had a seating capacity of 160, which meant that blocks had to be fed in three shifts. George Omi recalls a colored tag system. "We had to wait until everyone with white tags had eaten—we had blue tags, since we were among the last to register," he wrote. "The men grumbled about how long they waited and how confusing the tags were." Food was served cafeteria style. In his May 27 report, Mundell wrote that the "worst problem in the mess section has been to get workers who are willing to work in kitchens particularly dish washers." "Storage of refuse at several mess buildings was very unsatisfactory," observed Coffey in his sanitation report. "Cans were not covered, empty cans, and sometimes garbage had been dumped on the ground outside the mess buildings, and flies were attracted in great numbers." [5]

Given the location and the season, the heat at the camp was something many inmates recalled. "And it was the heat of summer, and the San Joaquin valley, a hundred and ten and hundred twenty degrees," remembered Marian Shingu Sata. "It was the most miserable few weeks, I'll never forget that." Sadami Hamamoto remembered 110° temperatures even under a tree in the school area. In her memoir, Jeanette Arakawa wrote that after dinner, "folks gathered outside their apartments," bringing chars outside "to escape the heat trapped in their rooms." Some inmates also found the grandstands to be an area where they could escape the heat. [6]

As at other assembly centers, inmates were subjected to daily roll calls that began on June 2, with weekly barrack inspections starting the week of June 10. The twice daily roll calls were at 6 am and 10 pm, though the earlier roll call was canceled after three weeks. Lights out was at 10:30 pm. [7]

Camp Population

Essentially the entire population of the Stockton Assembly Center came from Stockton, Lodi (about fifteen miles north of Stockton) and nearby farming areas in San Joaquin County. Given their proximity, the camp filled quickly, with the first inmates arriving on May 10 and camp reaching its peak population of 4,271 just eleven days later. The vast majority arrived by bus either from the Civil Control Station in Stockton or the one in Lodi; a few drove their own cars. [8]

| Exclusion Order # | Deadline | Location | Number |

| 50 | May 13 | City of Stockton | 1,648 |

| 70 | May 21 | North San Joaquin County/Lodi | 2,638 |

Source: John L. Dewitt, Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 (Washington D.C.: U.S. Army, Western Defense Command), 363–66. Exclusion orders with fewer than twenty inductees not listed. Deadline dates come from the actual exclusion order posters, which can be found in The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement: A Digital Archive, Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley, http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_b016b01_0001_1.pdf and http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_b016b01_0001_2.pdf .

| Arrival Date | Number |

| May 10 | 197 |

| May 11 | 23 |

| May 12 | 404 |

| May 15 | 1,016 |

| May 16 | 15 |

| May 18 | 531 |

| May 19 | 698 |

| May 20 | 982 |

| May 21 | 394 |

| May 22 | 4 |

| May 23 | 1 |

| May 24 | 1 |

Source: Harold Mundell, Report to Secretary of War, May 27, 1942, pp. 4–6, Stockton Assembly Center, General Correspondence File, Stockton Center Manager, Report—Secretary of War, Reel 207, NARA San Bruno.

In a 1944 interview, Tsugio Kubota observed that the rural young people were influenced by the more urban youth from Stockton proper. In particular, had they remained at home, "they never would have been able to have all those dances because the parents would not have approved... and wouldn't have had the opportunities to meet the social groups that existed in camp." According to Isao Buddy Sato, among the young men at Stockton, "[n]obody wore zoot suits" or "had a pachute (sic) haircut," nor were there any gangs, but that once the group transferred to the Rohwer, Arkansas, concentration camps, [t]hey learned all of these things from the Los Angeles fellows."

| Departure Date | Camp | Number |

| September 14 | Rohwer | 249 |

| October 3 | Rohwer | 512 |

| October 5 | Rohwer | 515 |

| October 7 | Rohwer | 426 |

| October 9 | Rohwer | 423 |

| October 11 | Rohwer | 417 |

| October 13 | Rohwer | 432 |

| October 15 | Rohwer | 414 |

| October 16 | Gila River | 220 |

| October 17 | Rohwer | 425 |

Source: John L. Dewitt, Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 (Washington D.C.: U.S. Army, Western Defense Command), 282–84.

Nearly the entire population of Stockton went to Rohwer. An advance group of 249 left for Rohwer on September 14. Regular transfers began on October 3, starting with Block 1 and some of Block 8. The last group left for Rohwer on October 17. The lone group that did not go to Rohwer were the 220 sent to Gila River. This group mainly consisted of tuberculosis patients and their families, the rationale being that the warmer and drier weather would be better for them. Stockton was open for 161 days; in that time, there were twenty-six births and ten deaths.

[9]

Staffing

The Stockton Assembly Center had two managers over the course of its life. Thirty-two-year-old Harold Mundell arrived on April 6 to become its first manager; he had been the state director of employment for the WPA in New Mexico and lived in Santa Fe. He remained at Stockton for a little over three months, returning to his former job on July 15. He was succeeded by Assistant Manager Asa S. Nicholson, a thirty-six-year-old Texan who had also come from the WPA organization in New Mexico. Nicholson remained as manager until closing. His successor as assistant manager was William Dougherty, who had held the same position as the Marysville Assembly Center until its closing at the end of June.

Many of the other managerial staffers were also from the WPA. Among them:

Harry N. Clifford, chief steward: fifty-year-old who came from the WPA in Monterey, California

Edmund B. Levy, director of service division (includes education, the library, information office, post office, religion, and center store): thirty-three-year-old who came from the Sacramento WPA District and who had also been among the staff at Manzanar at its opening

Jack McFarland, supervisor of recreation: twenty-nine-year-old who had been the editor of the Stockton Independent as well as staffer for the San Joaquin County Fair Association

Martin Murphy, fire chief: sixty-five-year-old former Stockton fire chief

Chris Nickols, police chief, age forty-two

B. T. Parsons, superintendent of works division: forty-six-year-old who had worked for the WPA in Stockton and had also come from Manzanar [10]

Institutions/Camp Life

Community Government

Shortly after the bulk of the inmates had arrived in late May, Camp Manager Mundell appointed two inmate organizations. The first was a set of eighteen block representatives, two from each of the nine occupied blocks:

Block 1: Sam Funamura; Nobie Matsumoto

Block 2: Paul Sato; George Hisaka

Block 3: Ted Oseto; Al Kawasaki

Block 4: Jim Okino; Miss Kiyoko Hattori

Block 5: Fred Ito; Miss Misao Hiramoto

Block 6: Henry Usui; Miss Sammie Chikaraishi

Block 7: Ted Mirikitani; Miss Sumiko Utsumi

Block 8: George Suzuki; Archie Miyamoto

Block 9: Shigeo Kishida; Harold Nitta

This group seems to have functioned much as block managers would in the later WRA camps, being responsible for the daily roll calls and to "act as superintendents in the policing and maintaining of barracks, utility buildings, and mess halls within their blocks," according to a report by Mundell. All of the appointees were Nisei and at least four were women. [11]

Mundell also appointed five councilmen, to a body he called the "Advisory Committee on self-government," which met for the first time on May 28. This group included Harry Itaya, Toshi Iwasaki, Ted Ohashi, Paul Shimada, and Yumi Sato. All were Nisei and two of the five were women. The group met with Mundell "at least once a week" and with the block representatives twice a week. In his June 23 report, Mundell wrote that he "planned to hold an election in the near future to elect Councilmen and Representatives by popular vote." [12]

That planned election was temporarily shelved by new WCCA rules that banned community government. Eventually, through a convoluted election process aimed at forming an advisory council that included both Issei and Nisei in proportion to their population in the camp, a group of twenty-one was elected on August 17, out of which the camp manager, Asa S. Nicholson, selected four Nisei and three Issei: Lloyd S. Shingu, Tom Hata, and Kakuzo Kawasaki (Issei); Sam Funamura, (Miss) Misao Hiramoto, Toshi Iwasaki, and Ted Mirikitani (Nisei). With plans for the transfer to WRA camps underway, it is not clear to what extent this new advisory group functioned. [13]

Education

Given its long lifespan, Stockton had a relatively extensive if makeshift inmate-run educational program despite the WCCA's lack of a budget for supplies or equipment. Soon after the bulk of the population had arrived, inmates organized at the end of May and early June. Stewart Nakano became the superintendent of schools, Grayce Kaneda headed adult education, and Toshiko Morita headed the grammar school teaching staff. Grammer school attendance reached four hundred per day, while about three hundred high school students met with inmate "experts" on various subjects, while representatives from local high schools visited the camp "to collect papers of the students and to give advice in future work" every morning. "There were classes set up by professional evacuees, like music lessons and classes such as those offered in schools—English, et cetera," recalled Sadami Hamamoto in a 2011 interview. [14]

Given the lack of funding, inmate educators exercised great ingenuity. The grandstand was used for the elementary grades while the nursery school used the grandstand as well as the rooms under the grandstand. The high school tutoring went on in "a special study room, located above one of the 'live stock barns' near the grandstand." Equipment and supplies came in the form of donations from various charitable bodies as well as from the City of Stockton. [15]

Medical Facilities

The camp hospital was located in a separate building northeast of the race track and just north of Block 8. Though not stated in any of the contemporaneous material, it is likely that the building Mundell described as "large, high-ceilinged, arc-roofed" was an existing one. It contained nine wards with a total of seventy-two beds, along with an operating room in which "[m]inor surgery can readily be performed," the more difficult cases being taken to the local county hospital. Dr. Hajime Kanagawa of Stockton headed the medical staff that included six other doctors: Junji "Jeep" Hasegawa, Masaki Yayoshi, Wilfred Gotanda, Kensuke Uchida, and George Sasaki. Head Nurse Dorothy Kato was joined by Mary Hashimoto and Chitose Aihara, the latter two arriving from the Salinas Assembly Center after that camp had closed on July 4. The dental clinic served an average of twenty patients a day, while Paul Matsumoto headed the pharmacy. Most of the hospital staff lived in the adjacent Block 8, as did some of the ambulatory patients. [16]

Library

The camp library was located just west of the hospital in a room above a barn. Operated as a branch library of the Stockton City Library, its head librarian was Ken Hasegawa. For the month of July, there 12,132 patrons who checked out 3,625 books and 912 magazines; for August, the figures were 10,769 patrons, 2,578 books and 712 magazines lent. Operating hours were 9 am to 9 pm. The library closed on September 21. Most of the book stock of the library, a total of 2,124 books, traveled with the inmates to the Rohwer WRA camp. [17]

Newspaper

The camp newspaper was the El Joaquin , which generally appeared twice a week with six-page mimeographed issues on Wednesdays and Saturdays. The newspaper staff worked out of an office under the grandstand that included one typewriter and a mimeograph machine. In addition to general information about the camp, most issues included profiles of white staff, updates on other assembly centers, a variety of columns, two pages of sports news, and a cartoon featuring a bucktoothed, sombrero clad Nisei boy named Pancho, created by George Akimoto. There were thirty-four regular issues of the El Joaquin , along with a thirty-five-page final issue dated September 28. A staff box only appeared in the final issue:

Editor: Barry Saiki

Art Editor: George Akimoto

News Editor: Mary Yamashita

Feature Editor: Sus Hasegawa

Contributing Editor: Patti Okura

Special Correspondent: Jimmy Doi

Sports Editor: Fred Oshima

Soc.-Rec. Editor: Teri Yamaguchi

Business Manager: Bob Takahashi

Reporters: Sakiko Kato, George Kaneda

Techician: Jun Kasa

Typists: Sumiye Kiramoto, Toshiko Oga

Okura was part of the advance group to Rohwer. Saiki became one of the editors of the Rohwer Outpost , while Akimoto created a new cartoon character named "Lil Dan'l" for the Outpost. [18]

Religon

Both the Buddhists and the Christians held regular Sunday services at opposite ends of the grandstand. Given the largely rural population, the Buddhists vastly outnumbered the Christians, with as many as 1,000 attending Buddhist services and Sunday School vs. only around 150 for the Christians. Revs. Enryō Unno and Seikaku Mizutani led the Buddhist Sunday school. [19]

Recreation

As at other assembly centers, recreational activities were influenced by the availability of space and equipment. The main open area available for sports was between Blocks 7 and 8, east of the racetrack. Softball, volleyball, touch football, judo, and sumo were among the activities that used this area. According to Mundell's May 27 report, sumo was the most popular spectator sport. An upstairs area of the grandstand was used as a card and game room for older inmates. There were also four Boy Scout and Cub Scout troops. Weekly dances featured photograph record and radio soundtracks, and group singing events that required virtually no equipment were frequent and popular. The dances were not without detractors, as a notice in the El Joaquin warned young people that those failed to return "promptly and quietly" to their barracks afterwards could cause the cancellation of future dances. Some could be spotted canoodling in the grandstand and empty stable areas. [20]

Store/Canteen

The camp canteen was located in a small building east of the grandstand. Opening on May 15, it sold snack foods, newspapers, toiletries, and other similar items. It accepted only WCCA issued coupons as payment. [21]

Visitors

The visitor building was located north of the hospital in the northeastern corner of the property. It was open daily from 1 to 4 pm. Daily visitors averaged about 250 to 300. [22]

Other

A post office and information booth were located under the grandstand. The post office was staffed by someone from the Stockton Post Office on Mondays through Saturdays and provided standard post office services. Mail arrived twice a day and inmate staffers from the information section delivered it to the blocks. [23]

Stockton was also one of the assembly centers from which inmates were allowed to leave in order to do vital sugar beet harvesting work on the outside. Two hundred and three inmates had left Stockton for the beet fields prior to the transfer to Rohwer. [24]

Chronology

April 6

Director Harold Mundell arrives and sets up headquarters at the camp.

May 1

John DeWitt,

Karl Bendetsen

and others from the WCCA office conduct an inspection visit of the completed Stockton Assembly Center.

May 10

First 197 inmates arrive.

May 21

Peak population of 4,271 reached.

May 30

First issue of the

El Joaquin

appears.

June 2

Twice daily roll call (6 am and 9 pm) instituted. (Later in June, morning roll call is canceled.)

Mundell appoints 18 block representative and five councilmen.

June 5

Graduation ceremony for seniors from Stockton (36) and Lodi (44) high schools. The principals of the two schools come to pass out the diplomas.

About 110 leave to pick sugar beets in Idaho.

June 8

Summer school for grammar school and 7th, 8th grades begins in the grandstand. Grayce Kaneda is the supervisor.

June 14

All Center Sumo Tournament features 100 wrestlers. 2,000 spectators attend the tournament.

June 15

First wedding at Stockton AC takes place, with Sumiko Ito and Ryoichi Horibe, both of Stockton, as the principals.

July 2

First pay checks covering the May 10 to June 9 period go out to 1,028 workers totaling over $6,000.

July 4

"Fourth of July Frolic" includes judo and sumo tournaments as well as men's and women's all-star softball games and Japanese cultural performances.

July 15

Obon festival dance at 8 pm draws 500.

July 18

Talent Revue at the Platform; twenty performers of both English and Japanese numbers featured.

July 21

Second group of 23 sugar beet workers leave for Montana.

July 24

10 pm to 6 am curfew goes into effect.

July 26

Camp "World Series" of softball matches the Block 5 Reds against the All-Center Poop-Outs. Despite the Poop-Outs undefeated record, the Reds open as 2–1 favorites. The Reds win in two straight games by 12–1 and 31–12 scores before a two-day crowd of 5,000.

July 27

Camp barber shop opens, led by head barber Fred Ito. Over 100 customers come on the first day.

July 28

Art exhibit featuring the students of the adult education class taught by Louie Shima and Hiroki Mizushima at Edex Hall for three days. 2,500 attend.

Aug. 17

Center elections: 1,918 voters elect twenty-one members of the Advisory Council, 17 Nisei and 4 Issei.

Aug. 21

All-Center Art Exhibit at Edex Hall; the three day exhibit "surpass[es] the first exhibit by far." 5,531 attend.

Aug. 22

All-Center Speech exhibition features six Nisei speakers.

Aug. 28

End of summer school term.

Sept. 1

Koichi Inouye leaves for the Chicago School of Design, the first to leave Stockton under the auspices of the

NJASRC

. He will be followed by Arthur Iwata, a UC graduate who will leave two days later to attend Washington University in St. Louis to enter a Master's program in art.

Sept. 5

Army searches all barracks for contraband, starting at 8 am. They completed the search of 900 "apartments" by 3 pm.

Sept. 9

Relocation order is announced: most in Stockton will go to Rohwer.

Sept. 10

31 men leave to do sugar beet work in Montana.

Sept. 14

Advance crew of 250 leaves for Rohwer, a combination of key workers who were more or less drafted, and volunteers.

Sept. 15

41 more leave for beet work in Montana.

Sept. 18

Last day for grammar school and nursery.

October 17

The last inmates leave Stockton for Rohwer.

Quotes

"Well, the one thing that I remember vividly was the heat, and there was no shade unless you went to grandstands and stood in the shade of that. And it was the heat of summer, and the San Joaquin valley, a hundred and ten and hundred twenty degrees, and then chicken pox broke out, and we all, all the kids, got chicken pox. It was the most miserable few weeks, I'll never forget that."

Marian Shingu Sata, 2009

[25]

"It was like moving from the city to the country, except that this country had a fence around it."

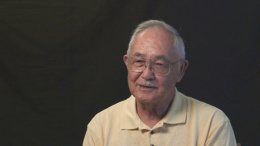

George Omi, 2016

[26]

Aftermath

The San Joaquin Fairgrounds remains in use and hosts an annual county fair. The actual site of the assembly center is now a fairgrounds parking lot.

In 1980, the Stockton site along with ten other assembly center sites was designated as California Historical Landmark No. 934. Local Japanese American community groups worked with the state to put up a monument located at the main entrance to the fairgrounds, consisting of a plaque mounted on a one-ton feather rock. The monument was dedicated on June 2, 1984. [27]

Notable Alumni

Miki Hayakawa

, painter and printmaker

Janice Mirikitani

, poet

Grayce Uyehara, redress movement activist

For More Information

Arakawa, Jeanette. The Little Exile . Berkeley, Calif.: Stone Bridge Press, 2017.

Burton, Jeffery F., Mary M. Farrell, Florence B. Lord, and Richard W. Lord. Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites . Western Archeological and Conservation Center, National Park Service, 1999, 2000. Foreword by Tetsuden Kashima. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002. The Stockton section of 2000 version accessible online at http://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/anthropology74/ce16l.htm .

The Historical Marker Database. " Stockton Assembly Center ."

Omi, George. American Yellow . First Edition Design Publishing, 2016.

Stockton Assembly Center video. Japanese American Memorial Pilgrimages, 2018.

Footnotes

- ↑ El Joaquin , May 30, 1; Harold Mundell, Report to Secretary of War, May 27, 1942, pp. 1–2, Stockton Assembly Center, General Correspondence File, Stockton Center Manager, Report—Secretary of War, Reel 207, NARA San Bruno; Narrative Reports, Harold Mundell to R. L. Nicholson, Apr. 30 and May 13, 1942, Stockton Assembly Center, General Correspondence File, Stockton Center Manager, Weekly Narrative Reports, Reel 209, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Mundell, Report to Secretary of War, May 27, 1942, 11, 13; "Volunteers for War Relocation Center," Stockton Assembly Center, General Correspondence Files, Stockton Center Manager, Evacuee – Transfer to War Relocation Projects, Correspondence and Instructions, Reel 207, NARA San Bruno. Though the El Joaquin map shows barracks 179 to 196 as being in Block 10, there is no indication that inmates lived in these, as lists of block representatives and of the 250-member advance crew to Rohwer list only addresses in Blocks 1 to 9. A description of the order that blocks will be transferred to Rohwer in the final edition of the El Joaquin (page 3) as well as a population list of the blocks (page A4) also only mention Blocks 1 to 9.

- ↑ For "horse stall" accounts by former inmates, see Alfred "Al" Miyagishima Interview by Tom Ikeda, May 13, 2008, Denver, Colorado, Segment 16, Manzanar National Historic Site Collection, Densho Digital Repository, http://ddr.densho.org/media/ddr-manz-1/ddr-manz-1-27-transcript-c0be73a046.htm ; Marian Shingu Sata Interview by Tom Ikeda, Segment 9, Los Angeles, Sept. 23, 2009, Densho Visual History Collection, Densho Digital Repository, http://ddr.densho.org/media/ddr-densho-1000/ddr-densho-1000-262-transcript-e291cf5419.htm ; and George Omi, American Yellow (First Edition Design Publishing, 2016), 74. Harold Mundell, Bi-Weekly Report, May 2, 1942, Stockton Assembly Center, General Correspondence File, Stockton Center Manager, Weekly Narrative Reports, Reel 209, NARA San Bruno; Philip J. Coffey, "Sanitation at Japanese Assembly Center, Stockton, California, May 14, 1942," May 23, 1942, p. 1, Stockton Assembly Center, General Correspondence File, Stockton Center Manager, U.S. Department Public Health – Correspondence, Reel 208, NARA San Bruno; El Joaquin, Aug. 5, 4.

- ↑ Coffey, "Sanitation at Japanese Assembly Center," 1–2; Mundell, Report to Secretary of War, May 27, 1942, 13–14; Jeanette Arakawa, The Little Exile (Berkeley, Calif.: Stone Bridge Press, 2017), 105; Omi, American Yellow , 73.

- ↑ Coffey, "Sanitation at Japanese Assembly Center," 2; Omi, American Yellow , 72–73; Mundell, Report to Secretary of War, May 27, 1942, 14.

- ↑ Marian Shingu Sata Interview, Segment 9; Sadami Hamamoto, interviewed by Warren Nishimoto and Michi Kodama-Nishimoto, Hilo, Hawai'i, Sept. 27, 2011, p. 283, Center for Oral History, University of Hawai'I at Manoa, accessed on Mar. 5, 2020 at https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstream/10125/23309/captive_6_hamamoto.pdf ; Arakawa, The Little Exile, 107; Alfred "Al" Miyagishima Interview, Segment 16.

- ↑ El Joaquin , June 10, 2, June 24, 3, and July 22, 1.

- ↑ John L. Dewitt, Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 (Washington D.C.: U.S. Army, Western Defense Command), 227, 363–66; Mundell, Report to Secretary of War, May 27, 1942, 4–6.

- ↑ Dewitt, Final Report , 282–84; El Joaquin , Final Edition, 3, 5, 6; Alfred "Al" Miyagishima interview, Segment 17.

- ↑ Profiles from various issues of the El Joaquin and from Mundell, Report to Secretary of War, May 27, 1942.

- ↑ Harold Mundell, Bulletin #25, June 2, 1942, Advisory Council Japanese, General Correspondence File, Stockton Center Manager, Report—Secretary of War, Reel 207, NARA San Bruno; El Joaquin, June 3, 2; Letter, Harold Mundell to R. L. Nicholson, July 7, 1942, Advisory Council Japanese, General Correspondence File, Stockton Center Manager, Report—Secretary of War, Reel 207, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Mundell, Bulletin #25, June 2, 1942; El Joaquin, June 3, 2; Letter, Mundell to Nicholson, July 7, 1942; Harold Mundell, Weekly Narrative Report, June 23, 1942, Stockton Assembly Center, General Correspondence File, Stockton Center Manager, Weekly Narrative Reports, Reel 209, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ El Joaquin , Aug. 5, 1; Report of the Election of an Advisory Council in Accordance with Supplement Eight to W.C.C.A. Operation Manual, [Aug. 26,1942], Advisory Council Japanese, General Correspondence File, Stockton Center Manager, Report—Secretary of War, Reel 207, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ El Joaquin , May 30, 5, June 13, 1, and Aug. 8, 4; Mundell, Report to Secretary of War, May 27, 1942, 24–25; Sadami Hamamoto interview, 283.

- ↑ Mundell, Report to Secretary of War, May 27, 1942, 24–25.

- ↑ Mundell, Report to Secretary of War, May 27, 1942, 22–23; El Joaquin , June 13, 2, July 11, 1, Aug. 5, 4, and Aug. 12, 3.

- ↑ Mundell, Report to Secretary of War, May 27, 1942, 30; El Joaquin , May 30, 3, June 10, 3, Sept. 2, 3, and Sept. 16, 4; "Special Report: Rohwer Relocation Center Library," [Reports Office], Jan. 29, 1944, The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement: A Digital Archive, Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley, BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder Q1.25, https://oac.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/k69k4jdk/?brand=oac4 .

- ↑ Information from various issues of the El Joaquin , as well as Mundell, Report to Secretary of War, May 27, 1942, 30.

- ↑ Mundell, Report to Secretary of War, May 27, 1942, 27; Duncan Ryūken Williams, American Sutra: A Story of Faith and Freedom in the Second World War (Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2019), 144, 381n31.

- ↑ Mundell, Report to Secretary of War, May 27, 1942, 26; El Joaquin , June 10, 3, July 1, 2, and Aug. 8, 5; Tsugio Kubota interview, 48.

- ↑ Mundell, Report to Secretary of War, May 27, 1942, 26; El Joaquin , May 30, 5; Harold Mundell, Weekly Narrative Report, May 19, 1942, Stockton Assembly Center, General Correspondence File, Stockton Center Manager, Weekly Narrative Reports, Reel 209, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ El Joaquin , May 30, 5 and June 17, 4.

- ↑ Mundell, Report to Secretary of War, May 27, 1942, 29.

- ↑ "Record of Inductions and Transfers as of October 17, 1942," Stockton Assembly Center, General Correspondence File, Stockton Center Manager, Evacuee-Induction, Reel 207, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Marian Shingu Sata Interview, Segment 9.

- ↑ Omi, American Yellow , 73.

- ↑ Pacific Citizen , May 18, 1984, 2 and June 22, 1984, 1; "Stockton Assembly Center," HMdb.org, The Historical Marker Database, https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=128368 ; San Joaquin Fair website, https://www.sanjoaquinfair.com/p/getconnected/history , both accessed on March 5, 2020.

Last updated Jan. 15, 2024, 4:41 a.m..

Media

Media