Varsity Victory Volunteers

In February 1942, a small band of University of Hawai'i undergraduates formed the Varsity Victory Volunteers (VVV or "Triple V"). These young men volunteered to serve as a manual labor support group for the U.S. Army's 34th Engineers at Schofield Barracks on the island of O'ahu. After Pearl Harbor, Japanese Americans, including Nisei , American-born citizens, were declared "enemy aliens" and prohibited from entering the American military. Discouraged, these college students petitioned the military governor to find a way for them to contribute to the war effort. For one year, 169 young Japanese Americans became the leading wedge of a multi-racial strategy to incorporate the large and critical Japanese American community in Hawai'i, in sharp contrast to the mass incarceration of 120,000 of their cousins on the continent of the United States of America. The VVV disbanded in January 1943, so its members could join the 442nd Regimental Combat Team or the Military Intelligence Service as Japanese language experts.

Immediately after aircraft of the Japanese Imperial Navy attacked Pearl Harbor and several other military installations in Hawai'i early on the morning of December 7, 1941, members of the University of Hawai'i's Reserved Officers Training Corps (ROTC) were ordered to campus and into combat. Most of that ROTC, mandatory on campuses of land-grant colleges, was comprised of Nisei but no one in authority in that time of crisis questioned the order just because they looked like the enemy. There were rumors that Japanese paratroopers had landed in the hills adjacent to their campus so the young, untrained, students were handed old rifles with a single clip of five shells to defend Honolulu. Fortunately, this was just another of the many rumors floating throughout the population and the boys returned safely.

On that very afternoon the ROTC boys were invited to join the Hawaii Territorial Guard (HTG), an emergency military unit designed to replace two National Guard outfits which had been federalized to defend against possible Japanese invasion. The HTG volunteers were issued uniforms and weapons to guard against potential Japanese or internal threats to critical sites like power stations, reservoirs, hospitals, and food warehouses. The several hundred Japanese Americans became the single largest ethnic group in the HTG. But six weeks later, on January 21, 1942, General Delos Emmons , military governor under martial law, ordered that the HTG be disbanded. The next day, the HTG was reformed, this time without any of the Nisei on the rolls. This transparent racial move was extremely discouraging to idealistic young men who felt they were serving their country.

Fortunately for Japanese Americans some of Hawai'i's key leaders had been considering, even before Pearl Harbor, what life would be like for a multi-racial society AFTER the U.S. won the inevitable war against Japan. To that end, resolving the "Japanese question" was absolutely vital since there were about 160,000 Japanese Americans—almost 40% of the total population—who were so integral to economic, social, and cultural life. And, with a growing proportion of voting age Nisei entering the political arena, they would inevitably become central to the democratic process. A Morale Section was appointed to serve as liaison between the civilian territorial government and the military governor's office; it was the key unit to maintain stability under martial law . Its members included Caucasian YMCA leader Charles Loomis, Chinese American YMCA Secretary Hung Wai Ching , and Japanese American school principal Shigeo Yoshida . This was an astonishing cast, especially the inclusion of Yoshida who became a leader of the group. On the U.S. mainland, such a forward-looking operation would have been unthinkable.

When the former ROTC and HTG warriors returned to campus, depressed by their recent dismissal from service to their country, Hung Wai Ching encouraged them to "turn the other cheek" and petition the military governor to accept them as volunteers in the war effort. The students recruited friends and 130 of them submitted a petition that read, in part:

Hawaii is our home; the United States our country. We know but one loyalty and that is to the Stars and Stripes. We wish to do our part as loyal Americans in every way possible and we hereby offer ourselves for whatever service you may see fit to use us.

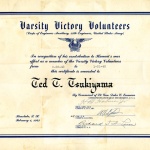

A month later, on February 25, 1942, 155 students assembled on campus for an official ceremony after which they were trucked to the Schofield army base. Eventually some 169 Japanese American youth served in the VVV, including senior supervisor Ralph Yempuku. Their officers included Captain Richard Lum, a Chinese American army officer; Lt. Thomas Kaulukukui, a Native Hawaiian and former All-American running back; one Caucasian officer was included but several Native Hawaiians were prominent and critical additions. Finally, Hung Wai Ching added several Japanese Americans who were not college students in order to demonstrate that loyalty and willingness to sacrifice extended beyond the educated college cohort. The ethnic/racial composition was both deliberate and strategic, designed to emphasize unity of mission. Thus, the Japanese American community was blessed with an important handful of key allies, including Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) field director, Robert Shivers ; university trustee, Charles Hemenway; police captain, John Burns and Reverend John Young.

For a full year, these young men divided themselves into "gangs" which took on various tasks, including breaking rocks into gravel, finishing pre-fabricated buildings, surfacing roads, building office furniture and field ice boxes for the troops, and cooking for the entire unit. They gave blood, bought war bonds, did community service, all with considerable public fanfare, signifying to the entire population and to Washington, D.C. that Japanese Americans were wholeheartedly behind the war effort. Since most were university students, they found means to participate in seminars taught by faculty who were willing to drive to Schofield Barracks, a considerable trip. The young men participated in essay contests run by the university and attended Saturday night dances hosted by Japanese American co-eds on campus. They quickly created a newspaper, held interminable unit meetings to discuss everything from wartime democracy to the foul stench emanating from common urinals. At one point chief cook Richard Chinen, a champion amateur boxer, walked away from the VVV because he felt that his recruiting non-university types was being disparaged. Ralph Yempuku eventually persuaded him to return.

But while the actual manual labor did make a difference since the war in the Pacific received much less support until Europe was largely safe from the Nazi threat, the significance of the VVV effort was much wider and deeper. Hung Wai Ching visited President Roosevelt to report on the contributions and loyalty of the Nisei and Assistant Secretary of War John McCloy visited the quarry gang breaking rocks. Some of this certainly helped persuade FDR to allow for the creation of the segregated 442nd Regimental Combat Team in January 1943. Indeed, the VVV was alerted to the news before it became public and encouraged to volunteer for the new unit. When the 442nd stood in formation on the grounds of 'Iolani Palace before shipping out for training in Mississippi, VVV members were provided the honor of being placed in the front of the lines of new GIs.

The VVV was made up of highly diverse Japanese Americans, including street fighters from the ghettos of Honolulu to bookish geeks who went on to become college professors and everything in-between. Collectively, they became a beacon of hope for inclusion of an "enemy" race in a multi-racial, postwar society. The VVV also became the prototype of the " Model Minority ," an American ideal ethnic group which transcended racial oppression, succeeding through patience, cooperation, and hard work.

For More Information

Odo, Franklin, No Sword to Bury: Japanese Americans in Hawai'i during World War II . Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2004.

Last updated Dec. 19, 2023, 3:15 a.m..