Amache (Granada)

| US Gov Name | Granada Relocation Center |

|---|---|

| Facility Type | Concentration Camp |

| Administrative Agency | War Relocation Authority |

| Location | Amache, Colorado (38.0500 lat, -102.3000 lng) |

| Date Opened | August 27, 1942 |

| Date Closed | October 15, 1945 |

| Population Description | Held people from California: Los Angeles, San Diego, and Santa Clara Counties (Merced and Santa Anita Assembly Centers), northern California coast, west Sacramento Valley, and the northern San Joaquin Valley. |

| General Description | Located at 3,600 feet of elevation on a wind-swept prairie in southeastern Colorado 140 miles east of Pueblo, 16 miles east of Lamar, and 15 miles west of the Kansas border. The Arkansas River runs 2 1/2 miles north of the camp, but the 10,500 acres of land is arid when not irrigated. Vegetation includes wild grasses, sagebrush, and prickly pear cactus. |

| Peak Population | 7,318 (1943-02-01) |

| National Park Service Info | |

| Other Info | |

With the smallest overall population of the War Relocation Authority (WRA) camps , Amache was notable in other ways. The only camp established on what had been private land, Amache was located walking distance from the small town of Granada, Colorado. The original population of the camp came entirely from different areas of California, but was later augmented by inmates from the camps at Jerome and Tule Lake . Inmates ran a silkscreen shop, a cooperative store, and were successful at agricultural enterprises both within and outside of camp. Today the site of Amache and an associated museum in Granada are open for visitors.

Geography and Prewar History of the Site

The Granada Relocation Center, better known by its postal designation, Amache, was located one mile outside the small town of Granada, in southeastern Colorado. Before the war Granada was just one of the small farming towns that dotted the valley of the Arkansas River, which runs east a few miles north of the site. Lamar, the Prowers County seat and largest town in the county, is seventeen miles west. Geographically, Amache was located in the High Plains, a rolling, sandy prairie between the Rocky Mountains and the Great Plains. The area has a semi-arid climate, with low humidity and average annual rainfall. Summers are hot and dry with occasional severe thunderstorms or tornadoes. Winters are generally cold and dry but can bring heavy snowfalls. High wind speeds are common throughout the year and can create choking dust storms.

Despite the region's general aridity, the Arkansas River provided irrigation water for the fields along the bottomland of the valley where the soil was more suitable for agriculture. Long an important travel corridor, the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad and US Highway 50 ran through the valley, linking it to national transportation networks. Granada was founded in the late 1800s as a railroad town, but quickly transitioned to largely agricultural enterprises. The town and the region were tremendously hard hit by both the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl. It remained an economically depressed area until World War II.

Amache was the only concentration camp where the project area was in private ownership prior to the war. The entire project area was over 10,000 acres, but only 640 acres, or one square mile, was devoted to the central camp area. Housing the WRA administration, MPs, and inmates, the central camp was sited above the valley floor, on sandy lands used minimally for livestock grazing. The majority of the project acreage was earmarked for the camp's associated agricultural enterprises. It was comprised primarily of two previously existing facilities, the Koen Ranch and the X-Y Ranch. Despite their names, both parcels held mixed agricultural enterprises with existing irrigation and farm structures, including a working dairy farm. To create a consolidated area, another twelve small agricultural holdings were also included in the project area. Only one property owner was a willing seller and the majority of the land had to be taken through condemnation, an action that set a combative tone between the WRA and the local residents. [1]

The WRA Camp

Amache had the smallest population of the ten WRA camps, but because of transfers from other camps over 10,000 inmates passed though the camp. Despite a peak population of under 8,000, Amache was the 10th largest city in Colorado during the war. The original population derived from three main geographic areas, all in California: the Central Valley, the northern coast, and southwest Los Angeles. In time this original group would be joined by inmates transferred from other WRA facilities, including over 900 from Tule Lake, and over 500 from Jerome. They hailed almost evenly from rural and urban areas, and both Buddhist and Christian denominations were well represented in camp. Something that many shared in common was a connection to agriculture and horticulture, whether as farmers, produce and nursery men, or landscapers and gardeners. Among the more notable other professionals in the camp were two professors, two cartoonists from the Walt Disney studios, a concert singer, and a female lawyer.

Most numerically significant were inmates from California's Central Valley, living in a swath from Merced to its northern end. Importantly, three distinct farming colonies from the vicinity of Livingston, California, were represented in their entirety in the Amache population. Founded as the Yamato Colony by Kyutaro Abiko , a San Francisco newspaper publisher and businessman, they came to comprise three distinct but adjacent settlements, Yamato, Cortez, and Cressey. [2] They were tight-knit Japanese American communities before, during, and after the war. Although there were more concentrated Japanese American populations in the northern coastal towns of Petaluma and Sebastopol, many of the families from this region lived largely among non-Japanese. An example was the Hiranos, the only Japanese family in Sausalito. A teenager when his family was removed, George Hirano recalled getting off the bus in Santa Rosa and seeing more Japanese people than he had ever seen in his life. [3] The Amacheans from Los Angeles did not hail from Little Tokyo, but rather the southwestern suburbs, including a portion of the Seinan neighborhood. Many areas of Los Angeles had racially restrictive covenants, but there were none in the region bounded by Exposition, Adams, Vermont, and Arlington Avenues. Many Japanese Americans lived in this area, along with African Americans and Hispanics. [4]

The Granada Relocation Project administrator for the WRA was James G. Lindley, assisted by Donald E. Harbison. Another notable administrator was Joseph McClelland, the reports officer who was also the camp photographer and oversaw the newspaper, The Granada Pioneer . Lindley and his administration are regarded in a generally favorable light. Robert Harvey claimed that those inmates who knew Lindley, "felt he was an able administrator with a deep regard for fairness." [5] A number of the teachers at Amache petitioned successfully to move to the camp, in part to be able to better serve their students. [6] Among the unposed photographs in Joseph McClelland's personal collection, are images of WRA staff and inmates playing cards together. [7] The general lack of animosity was also reflected in the politics of Colorado's Governor Ralph Carr , the only western governor to support locating a WRA camp in his state. [8] A WRA community analyst reported early in 1943 that relations between groups at Amache were "infinitely better" than at any of the other WRA facilities and that the project administration functioned smoothly. [9]

The camp administration did have its hands full when the construction of the Amache High School created a public relations backlash. Still reeling from the Dust Bowl, the region had seen very little new construction for decades other than federally-supported projects. Local residents resented the expense of building a school specifically for Japanese American students. Superintendent of schools Paul J. Terry defended the new construction in the Lamar newspaper, stating that the students at Amache, "have left excellent schools on the Coast, and if we take away all education from them, we have a morale problem." [10] The fray was taken to the state and national level when Colorado Senator Edwin Johnson identified the construction as one of the ways the WRA was "pampering" the enemy. [11] Although the high school was completed, the plans for an elementary and middle school were abandoned on orders from the national office of the WRA.

Like all of the camps, Amache was thrown into turmoil by the loyalty questionnaire . However, the actual numbers of inmates who replied "no" to question 28 was the lowest percentage of any camp. [12] After the segregation hearings only 125 people were transferred from Amache to Tule Lake, while 993 Tuleans were sent to Amache. Tomo Nishizaki, one of the Amache community leaders, actively discouraged his friends from resettling in Japan. As recalled by his wife Fumiye, he told his friends, "Don't go home now, because it's going to be terrible." [13] The final number of Amacheans who were repatriated to Japan was 35.

The reaction to military service echoed that of the loyalty questionnaire. Amache had the highest rate of volunteerism of all the camps. A total of 953 men and women from Amache volunteered or were drafted for military service during WWII. Of this number, 105 were wounded and 31 killed in action. Among those killed was Kiyoshi Muranaga who was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor . (See Japanese Americans in the military during World War II .) However, not all Amacheans responded favorably to the notice for induction into the military. Thirty-one men from Amache were tried for draft evasion, found guilty, and sent to prison in Tucson , Arizona. (See draft resistance .)

Although many of the WRA camps had war-related industries, Amache was the only camp with a successful silkscreen shop. At the time, silkscreening was one of the best ways to crisply print in color, something required by the U.S. Navy for their training materials. Established in June of 1943, the Amache silkscreen shop produced over 250,000 color posters under a contract with the navy. The staff of forty-five also created many prints for use in camp, including calendars, programs for camp events, even souvenirs for the yearly carnival. The Amache silkscreen shop produced a colorful and visually distinctive record of life at the camp.

The agricultural efforts of the Amache inmates were also very successful, both inside and outside the camp. In 1943 alone, inmate farmers produced approximately 4 million pounds of vegetables, over 50,000 bushels of field crops, as well as successfully raising a wide range of livestock. Not only did the farms of Amache make the camp self-sufficient for many foodstuffs, but surplus was sent to other WRA camps. For example, in the fall of 1943, Amache sent 600 bushels of spinach each to Poston and Gila, with another 1,000 bushels sent to the U.S. Army. [14] Surrounded by farms and ranches, many Amacheans found ready temporary or permanent employment as agricultural laborers in the vicinity. The generally positive relationship with regional farmers was fostered in part by the efforts of Amacheans in the fall of 1942. Due to the wartime labor shortage and weather, the Colorado sugar beet harvest was under threat. Amacheans came out of the camps, some as paid laborers, but nearly 150 as volunteers, to help the surrounding farmers bring in the crop. [15]

The proximity of Amache to the town of Granada created a situation unique among the WRA camps. Inmates were close enough to Granada that walking into town to shop or even just visit a soda fountain was a common occurrence. The positive effect this had on camp morale was noted by the WRA. [16] Although some regional businesses were anti-Japanese, most came to see the Amacheans as valuable customers. Indeed by 1945, the Amache High School annual was filled with advertising from local businesses. Newman Drug Company is a good example. Before the opening of the camp, Edward Newman rented one of the largest buildings in Granada and brought in stock he thought would appeal to the inmates, including an entire warehouse of saké. [17] Newman employed Amache inmates in the store and also as the family nanny, [18] a practice fairly common in the area. After getting a release from Amache, Frank Tsuchiya started his own successful local business, the Granada Fish Market. Using his connections from running a fish market in Los Angeles, he was able to bring in sashimi grade fish to Granada. [19] The store also sold Japanese food hard to come by in camp such as soy sauce and noodles. [20] Evidence of these connections between camp and town are visible in the physical remains found during archaeological studies of Amache, including an abalone shell that likely derives from the Granada Fish Market, and swizzle sticks from a bar in Granada.

After the War

Many families with school age children waited to leave Amache until the summer of 1945, but in July there were still over 4,000 people in the camp. In the fall of 1945, inmates built a small structure at the camp cemetery out of the brick that once served as their barracks floors. Inside they erected a stone memorial, as well as wooden planks bearing the names of all 114 inmates who died at Amache. The camp officially closed on October 15, 1945. A few families were able to return to their homes and farms in California, especially those from the Yamato farming colonies. Some stayed on in the Arkansas River Valley or moved to Denver , taking advantage of new connections to Colorado made during the war. Chicago had been a key location for resettlement efforts at Amache and many former inmates continue to live in the Midwest. Following the closure of Amache, all but two buildings—the monument at the cemetery and a concrete structure built by the Amache Cooperative—were dismantled and removed from the site. Many of the buildings were destroyed, but a fair number were sold to area farms and schools. The camp area was purchased by the town of Granada, which continues to own the land and use the deep wells drilled for the WRA camp as their city water supply.

Remembering and preserving Amache has been, and remains, a very grassroots effort by many organizations and individuals. [21] The first pilgrimage to Amache in 1976 was associated with bicentennial events in the state of Colorado. Yearly pilgrimages began in the 1980s, led by the Denver Central Optimists Club, a civic group whose membership included former Amache inmates and their relatives. Now the Amache Club, they still lead the yearly pilgrimage to the camp cemetery on the third Saturday of each May. Also key has been the Amache Historical Society headquartered in Los Angeles and comprised primarily of former Amache inmates. They have taken the lead on Amache reunions, holding them both at the camp and in locations across the West. Key local support for preservation came from administrators and teachers at the Granada School District, especially John Hopper. A social studies teacher at the high school, Hopper inspired his students to learn about and preserve this important part of their own history. Now organized as the Amache Preservation Society, they maintain a small museum in Granada with a significant collection of objects, documents, and photographs related to the camp.

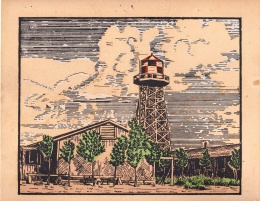

Visitors to Amache today still enter the barbed-wire enclosed central camp area at the original camp entrance. Near the entry are a series of informational signs erected by the National Park Service in partnership with the site management entity, the Friends of Amache. Near the entrance is also the brass plaque denoting that Amache was recognized in 2006 as a National Historic Landmark. That status derives in part from the high physical integrity of the central camp area which still contains its intact war era roadway system, most building foundations, and remnant landscaping created by Amache inmates, including living trees they planted. The cemetery, located in the far southwestern part of the camp, contains a more recent monument to the fallen soldiers of Amache, as well as the war era monument. By the end of 2012, visitors will also be able to see a reconstructed guard tower, as well as the Amache water tower, rebuilt in part from original materials. A recent study of all the Amache-related buildings in the region has identified several structures from camp, including barracks and a recreation hall, buildings that the Friends of Amache hopes to be able to return to the site. [22]

For More Information

"The Amache Japanese American Internment Camp Through Records at the Colorado State Archives." [Maintained by the Colorado State Archives, this page links to important primary documents related to Amache, including the correspondence of Governor Ralph Carr, whose strong support of the constitutional rights of Japanese Americans would cost him his political career.]

Amache Preservation Society. [This is the website maintained by the Amache Preservation Society in Granada, Colorado. Currently being rebuilt so it can host more archival documents, the website provides general history about Amache and its preservation, as well as a location for updates about events, such as the yearly pilgrimage.]

Amache Project. University of Denver (DU). [The University of Denver (DU) Amache Project is a community based project researching the tangible history of Amache, including intensive archaeological study of the camp. Results from that research, including photographs, newsletters, and a short documentary film, are available through the website.]

Camp Amache: The Story of an American Tragedy . Dir. by Don Dexter. DVD. Dexter Productions, 2007. [This 57 minute documentary uses footage of the camp and pilgrimages, historic photographs, and interviews to tell the story of Amache.]

Chang, Gordon H. ed. Morning Glory, Evening Shadow: Yamato Ichihashi and his Internment Writings, 1942-1945 . Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1997. [A professor of history at Stanford before and after the war, Ichihashi was among the hundreds of inmates transferred from Tule Lake to Amache in 1943. This is a collection of his writings (and a few by his wife Okei) about the entire experience of removal and confinement, including diary entries, letters, and a biographical essay by the editor.]

Harvey, Robert. Amache: The Story of Japanese Internment in Colorado during World War II . Dallas: Taylor Trade, 2004. [Harvey is the one of the few published works dealing exclusively with Amache. It is out of print but available at many libraries.]

Hosokawa, Bill. Colorado's Japanese Americans from 1886 to the Present . Boulder: University Press of Colorado. [Hosokawa's book focuses on the history of Colorado's Japanese American population, which grew significantly because of internment and Amache.]

Inada, Lawson Fusao. Legends from the Camp . Minneapolis: Coffee House Press, 1992. [Now the Poet Laureate of Oregon, Inada's family was transferred to Amache after the closure of the camp in Jerome. Several of the poems in this volume are about or set in Amache.]

The Japanese American Archival Collection. California State University, Sacramento. [The Japanese American Archival Collection at California State University, Sacramento curates a number of artworks and objects from Amache. Images of many of them are available through this website.]

Matsumoto, Valerie J. Farming the Home Place: A Japanese Community in California, 1919–1982 . Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1993. [Based on her dissertation research in the Cortez farming colony, this is one of the few published histories of a community whose residents were interned at Amache.]

Footnotes

- ↑ Robert Harvey, Amache: The Story of Japanese Internment in Colorado during World War II (Dallas: Taylor Trade, 2004), 61.

- ↑ Valerie J. Matsumoto, Farming the Home Place: A Japanese Community in California, 1919–1982 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1993).

- ↑ George Hirano, conversation with author, May 2011.

- ↑ Minoru Tonai, conversation with author, May 2011.

- ↑ Harvey, Amache , 207.

- ↑ Enola Kjeldgaard, Fourth Grade Teacher, Impressions of a Japanese Relocation Center: Lest We Forget. Personal files of the author.

- ↑ McClelland's personal color slides have been digitized and are curated at the Amache Preservation Society museum in Granada.

- ↑ Adam Schrager, The Principled Politician: The Ralph Carr Story (Golden: Fulcrum, 2008).

- ↑ John Embree, Report on Granada, January 30-February 1, 1943, War Relocation Authority Community Analysis Section, 1. Bancroft Library, University of California Berkeley.

- ↑ Lamar Daily News , Jan 22, 1943, 1.

- ↑ Harvey, Amache , 105.

- ↑ Bill Hosakawa, Colorado's Japanese Americans from 1886 to the Present (Boulder: University Press of Colorado), 103.

- ↑ Fumiye Nishizaki, typed manuscript of oral history by Dale Ann Sato, (Peninsula Center Library, Rolling Hills Estates, CA, Feb 8, 2005), 20.

- ↑ Granada Pioneer Vol I, No 73, Jun 12, 1943.

- ↑ War Relocation Authority, Granada Project Chronological History, National Archives.

- ↑ Embree, Report.

- ↑ Harvey, Amache .

- ↑ Bruce Newman, conversation with author Feb 2011.

- ↑ Bill Hosokawa, Japanese of Colorado , 103.

- ↑ Harvey, Amache , 127.

- ↑ Jennifer Otto, "Communities Negotiating Preservation: The World War II Japanese Internment Camp of Amache" in Southeast Colorado Heritage Tourism Report , ed. Rudi Hartmann (Wash Park Media: Denver, 2009), 125-138.

- ↑ Colorado Preservation Inc., Dismantling Amache: Building Stock Research and Inventory Related to the Granada Relocation Center (Denver: Colorado Preservation, Inc., Aug 2011).

Last updated Dec. 2, 2023, 6:21 a.m..

Media

Media