Seabrook Farms

Seabrook Farms, located in Cumberland County, New Jersey, was once one of the largest producers of canned, frozen, and dehydrated vegetables in America. By utilizing innovative farming, production, and distribution practices, it became a major food supplier to the U.S. military during World War II. To meet production needs, Seabrook hired immigrant workers as well as a large number of Japanese Americans recently released from concentration camps and "relocated" by War Relocation Authority (WRA) mandate. These Japanese American workers played a critical role in the Farms' success and even still today a Japanese presence exists in New Jersey.

Background

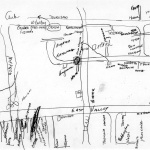

Charles Franklin Seabrook owned and operated Seabrook Farms after taking over his father's sixty-acre farm during World War I. By utilizing the newest technology to increase production such as installing overhead and movable irrigation pipes and introducing the use of tractors and trucks, Seabrook Farms became the first commercial growing enterprise in America with more than 250 acres devoted to intensive growing by 1920. [1] Seabrook also built thirty-five miles of roads, including most of modern State Highway 77 that became the conduit for Seabrook trucks moving products to markets in Philadelphia, New York, and elsewhere. He also constructed power and food-processing plants, a cold storage warehouse, several shops, a sawmill, dams for water storage, and the pipelines and pumping stations to supply the vast irrigation system he had designed. Additionally, Seabrook built houses for an increasing number of employees and two railroad connections that could compete for Seabrook Farms' business. In 1929, after the stock market crash, Seabrook made an agreement with General Foods that had purchased the Birdseye patent for quick-freezing food in retail packages to plant, pick, and freeze food. The Birdseye brand would dominate the frozen food market for many years thereafter and made Seabrook "the brightest spot in the economy of southern New Jersey." [2] Later Seabrook produced food under its own label and after developing sixty square miles of rich farmland in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware, became the "world's largest truck farm enterprise." [3] By the start of World War II, Seabrook farms had become the first agri-industry in the world and B.C. Forbes, founder of Forbes magazine, described Seabrook as the "Henry Ford of agriculture." [4]

Labor Needs and Imprisoned Japanese Americans

During its heyday during World War II, Seabrook Farms packaged 150 labels of frozen food and became the major supplier of vegetables to the military. Superior management teams, efficiency experts, and engineers were keys to Seabrook's success as it produced one-fifth of the nation's vegetables. However, the business suffered from the lack of a steady source of labor. Seabrook tried various measures to alleviate the labor shortage, hiring immigrants, women, students, disabled veterans, and persons deferred from the draft. The Farms even hired Jamaican workers and drew upon migrant workers: blacks from Florida and whites from West Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Arkansas.

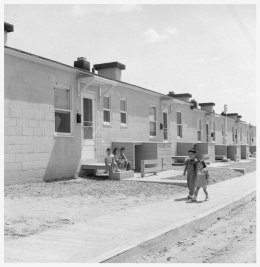

By 1944, Japanese Americans from West Coast concentration camps began to arrive for farm work as Seabrook's labor needs coincided with the WRA's mandate to "relocate" Japanese Americans. Throughout 1944, Seabrook officials brought in trial groups from the camps, sent recruiters to the camps, advertised for workers in camp newspapers, and placed favorable articles about Japanese Americans in local papers to calm the fears of residents about the arrival of a formerly incarcerated population. By August 1944, there were almost 300 Japanese Americans at Seabrook; 831 in December 1944 and by 1946 there was an average of 2,500 residents. The January 1947 estimate was between 2,300 and 2,700 persons and included 178 Japanese Latin Americans who had arrived from Crystal City internment camp. [5] The large number of arrivals created housing shortages for the laborers and many former internees were dismayed at the poor quality of housing that was reminiscent of the concentration camps. Seiichi Higashide, a former Japanese-Peruvian internee, described Seabrook as a "town of chain-linked fences" explaining that "the transfer to this place from our former life behind barbed-wire fences was no more than a shift from complete confinement to partial confinement." [6] Hours were long, work was difficult, and wages only started at fifty cents an hour although it depended on gender, type of work, and union status. There were also some complaints that white workers were being promoted over established Nisei workers.

Seabrook's Decline and Fate

For many Japanese Americans, working at Seabrook was a transitional phase as they began to leave to different areas including Chicago, New York, and the West Coast. By 1949, the Japanese American population had dwindled to 1,200 and by 1970s, there were just 530 Japanese Americans at Seabrook Farms. The decline in the number of workers coincided with the challenges the Farms later faced. Seabrook farms primarily supplied the Atlantic coast and did not extend beyond the Mississippi River to compete with western processors. National distribution would have committed the company to provide products one year in advance, challenging the company's claim of sending fresh vegetables from field to freezer in three hours. According to Sawada, this decision caused the eventual demise of Seabrook Farms as "its size and gross capitalization were too small to keep apace of alterations in the food-processing industry and to combat eventual usurpation by larger neoconglomerates." [7] By the mid-1970s, much of Seabrook's produce did not come from its own farmlands; instead it was imported from various parts of the United States including California, stored for an indefinite time, and later processed. Eventually the plant at Seabrook closed but a Japanese American presence at Seabrook continues to be felt as former and present Seabrook Japanese American community members founded the Seabrook Educational and Cultural Center.

For More Information

Chinen, Karleen. "Japanese Peruvians." Hawaii Herald 9:19 (October 7, 1988): 22-24.

Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians . Washington D.C.: Civil Liberties Public Education Fund; Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997.

Gardiner, Harvey C. Pawns in a Triangle of Hate: The Peruvian Japanese and the United States . Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1981.

Harrison, Charles H. Growing a Global Village: Making History at Seabrook Farms . New York: Holmes & Meier Publishers, Inc., 2003.

Higashide, Seiichi. Adios to Tears: the Memoirs of a Japanese-Peruvian Internee in U.S. Concentration Camps . Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2000.

Jacobs, Meg. Review of Seabrook at War: A Radio Documentary . The Journal for MultiMedia History 2 (1999). http://www.albany.edu/jmmh/vol2no1/seabrook.html .

Thomas, Dorothy Swaine. The Salvage . Berkeley: University of California Press, 1975.

Sawada, Mitziko. "After the Camps: Seabrook Farms, New Jersey, and the Resettlement of Japanese Americans 1944-47." Amerasia 13:2 (1986-87): 117-136.

Seabrook Educational and Cultural Center. http://www.seabrookeducation.org/ .

Shimada, Koji. "Education, Assimilation, and Acculturation: A Case Study of a Japanese American Community in New Jersey." Ph.D. diss. Temple University, 1975.

Footnotes

- ↑ Charles H. Harrison, Growing a Global Village: Making History at Seabrook Farms (New York: Holmes & Meier Publishers, Inc., 2003), 4.

- ↑ Harrison, Growing a Global Village , 7.

- ↑ Mitziko Sawada, "After the Camps: Seabrook Farms, New Jersey, and the Resettlement of Japanese Americans 1944-47," Amerasia 13:2 (1986-87): 119.

- ↑ Harrison, Growing a Global Village , 8.

- ↑ Sawada, After the Camps , 121.

- ↑ Seiichi Higashide, Adios to Tears: the Memoirs of a Japanese-Peruvian Internee in U.S. Concentration Camps (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2000), 182.

- ↑ Sawada, After the Camps , 119.

Last updated June 10, 2020, 3:53 p.m..

Media

Media

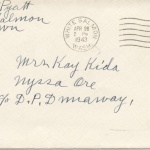

![Postcard from Fred F. Fujii to Mr. and Mrs. Okine, July 18, 1947 [in Japanese] Postcard from Fred F. Fujii to Mr. and Mrs. Okine, July 18, 1947 [in Japanese]](https://encyclopedia.densho.org/front/media/cache/34/ab/34abe145e2bab66f28baeb51656d5c2e.jpg)