Bainbridge Island, Washington

Residents of Bainbridge Island were the first Nikkei community to enter an incarceration camp during World War II. [1] Japanese immigrants had founded ethnic communities near the island's prominent sawmills and shipyards in the late 1800s and shifted to agricultural endeavors by the 1910s. After eleven months in Manzanar incarceration camp, the Bainbridge group was reunited with other Western Washington Nikkei at Minidoka incarceration camp. After the war, Nikkei reestablished their strong presence on Bainbridge Island.

Prewar Community

Approximately five miles wide and ten miles long, Bainbridge Island is located in Puget Sound between the Kitsap Peninsula and Seattle. Until the construction of the Agate Pass Bridge in 1950, only ferries and private boats connected the island to the mainland. A car ferry service to Seattle has operated since the 1920s.

Ethnic communes initially defined Bainbridge Island's demographics, but diminished as employment shifted towards agriculture. Japanese began arriving in the 1880s and the Japanese village of Yama soon contained more than fifty families. [2] From the 1870s to the 1920s, the Port Blakely Mill Company employed immigrants from British Columbia, Hawaii, China, Japan, Finland, Sweden and Italy. Islanders also worked at the Port Madison Mill and the Hall Brothers Shipbuilding Firm. The Moritani family introduced strawberry farms to the Island economy in 1908. This Nikkei-dominated industry produced two million pounds of fruit in 1940. [3] Zenhichi Harui and Zenmatsu Seko developed the twenty-seven acre Bainbridge Gardens, which contained a plant nursery, sunken garden, greenhouses, a grocery store, and a gas station. [4] Filipinos joined the island's diverse community in the 1920s and worked on many Nikkei farms.

While some Nikkei recall socially insular ethnic communities on Bainbridge, others speak of amicable relationships with white and Filipino Islanders. The public schools taught students of diverse backgrounds and Nisei students held many leadership positions. Commerce, sports competitions and religious organizations forged ties between Nikkei living on Bainbridge and those in Seattle.

Eviction

Nikkei on Bainbridge experienced unique hardships after the attack on Pearl Harbor. The Black Ball Line, the ferry that transported people and goods from the island to Seattle, denied passage to all generations of Nikkei until the company's headquarters ordered them to accept all people possessing documentation of U.S. citizenship. [5] The American Friends Service Committee stationed a group of volunteers on the island to act as "observers and errand-boys," bringing bank forms and contracts from Seattle to Issei confined to the island.

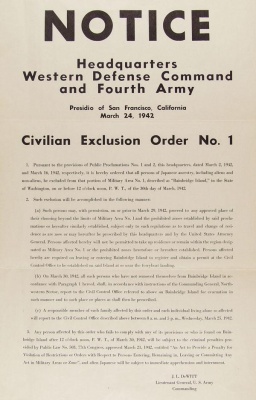

Bainbridge Island's close proximity to U.S. Navy facilities prompted Lieutenant General John DeWitt to call for their removal on March 24, 1942, the very day he issued Civilian Exclusion Order No. 1. Bainbridge residents had six days to sell or lease their farms, store belongings, find homes for pets, bid neighbors farewell and pack personal belongings.

As the first community to be removed, Islanders lacked local support systems and the government had inadequately prepared for the eviction process. Church groups helped other communities pack and store belongings, but the Seattle Council of Churches did not organize aid in time to help Islanders. [6] The greatest confusion concerned transportation of material possessions. Eviction posters instructed Islanders to limit their luggage to "that which can be carried by the family or individual. [7] However, the U.S. government had not decided definitively how to handle this issue. After many Islanders sold their belongings, army officers announced that the government would ship additional luggage to the camps. Nikkei began repurchasing items before learning that the army had not secured the allocation of these funds. [8]

On March 30th, army trucks conveyed Bainbridge's Nikkei from their homes, where families waited with their baggage, to the Eagledale ferry dock. Islanders noted the compassion with which the young soldiers from New Jersey conducted their duty. [9] Friends and neighbors, high school classmates and curious observers lined the Bainbridge docks to watch Nikkei board the ferry. Roy Dennis, the principal of Bainbridge High School, excused students wishing to say goodbye. [10] He also arranged for incarcerated seniors to finish the term through correspondence courses. [11]

At 11:20 am, the ferry Keholoken departed with 227 Islanders. Quickly moving from the ferry to a train bound for central California's high desert, the community left Seattle. After a multi-day train ride, soldiers directed Islanders to buses for the last leg of their journey to the Owens Valley Reception Center. [12]

Life at Manzanar and Minidoka

Owens Valley, later renamed Manzanar War Relocation Center, was the first camp prepared to receive detainees. But when Islanders arrived, the camp's sewer system and other crucial facilities were not completed. [13] Meals consisted of army rations. Guard towers, barbed wire fences, and additional barracks were still under construction.

After the Islanders left for California, the federal government ultimately sent most of Seattle's Nikkei to Minidoka, an incarceration camp in southern Idaho. Supported by white Protestant ministers working at Minidoka and Walt Woodward of the consistently sympathetic Bainbridge Review , Bainbridge Nikkei wrote letters to the War Relocation Authority (WRA), congress people and other outside contacts requesting transfers to Minidoka. Many missed family and friends confined in Idaho and others disliked the atmosphere of their California camp. Teenagers from Bainbridge clashed with those from Terminal Island. [14] White outsiders believed the Washingtonians were "much more advanced in . . . American ideas" than the Californians and warned that the Bainbridge group would "revert" back to Japanese habits and customs if they remained at Manzanar. [15]

Less than a year after their arrival, the WRA granted Islanders permission to rejoin other Washington Nikkei at Minidoka. On February 26, 1943, 177 Islanders from Manzanar arrived at Minidoka. [16] Five families declined the offer, choosing to stay near California family members in Manzanar. [17]

The Bainbridge Review

The Bainbridge Review continually assured readers of the assimilation and loyalty of Nikkei Islanders. With remarkable foresight, editors Milly and Walt Woodward paved the way for the ethnic community's return. The Review worked to create a positive attitude toward Nikkei on the island and never questioned that Nikkei continued to be part of the Bainbridge's community despite their absence. The Woodwards promoted high schooler Paul Ohtaki, the journal's janitor, to field reporter before the incarceration. His weekly column relayed the community's vital statistics and sports scores and conveyed the loyalty of Nikkei Islanders. Ohtaki wrote of the disagreements between Islanders and "Orientals" from California, and Walt Woodward noted that no Islander participated in the December 1942 riot at Manzanar. [18] Other incarcerated Islanders took Ohtaki's place when he left camp in July 1943. [19] The Woodwards hoped these reports would ease the transition as Nikkei returned home when the exclusion orders ended.

Several awards recognized the Woodwards' efforts, as did the naming of Woodward Middle School. David Guterson used Walt Woodward as a model for a character in his bestselling 1995 novel Snow Falling on Cedars . [20]

Post War

In April 1945, the first members of Bainbridge's Nikkei community, Saichi and Yone Takemono, returned to the island permanently. [21] Over half of Bainbridge's prewar Nikkei population returned after their eviction. [22] Islanders faced financial challenges upon their return, but many locals welcomed them back to the area and a number of incarcerated farmers retained their land with the help of non-Nikkei Islanders.

In 1952, Nikkei founded the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Community (BIJAC) to sponsor social activities and provide community support. Picnics and potlucks help maintain community ties among Nikkei living on and off of the island and several members organized an oral history project. While many Nikkei Islanders resisted the idea in the 1970s, volunteers persevered to compile the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Community Collection. Several BIJAC leaders sit on the board of advisors for the Only What We Can Carry Project, a nonprofit group based in Bainbridge that develops lesson plans for elementary and upper level students in the Pacific Northwest.

Numerous memorials honor Bainbridge's Nikkei. In association with Minidoka National Historic Site, island resident and renowned architect Johnpaul Jones designed the expansive Bainbridge Island Japanese American Exclusion Memorial at Eagle Harbor. The Japanese American community designed Haiku No Niwa , a garden at the Bainbridge Public Library, to honor their ancestors on the island. Junkoh Harui built a memorial for his parents in the reopened Bainbridge Gardens. An intermediate school was named after an Issei farmer, Sonoji Sakai. Exhibits at the Bainbridge Island Historical Museum tell the story of island Nikkei and their incarceration.

For More Information

Online Resources

Bainbridge Island Japanese American Exclusion Memorial.

Bainbridge Island Japanese American Community.

Bainbridge Review digital collection, Kitsap Regional Library.

Densho Digital Repository.

Photo Collections:

Bainbridge Island Japanese American Community Collection

Bainbridge Island Review Collection

Visual History Interviews:

Earl Hanson

Junkoh Harui

Fumiko Hayashida

Frank Kitamoto

Isami & Kazuko Nakao

University of Washington Libraries online exhibit.

Documentaries

Fumiko Hayashida: The Woman Behind the Symbol film. Stourwater Pictures, 2009.

Visible Target film. Produced by Cris Anderson and John de Graaf, 1985.

Secondary Sources

Woodward, Mary. In Defense of Our Neighbors: The Walt and Milly Woodward Story . Bainbridge Island, WA: Fenwick, 2008.

Footnotes

- ↑ In February 1942, the U.S. government forced Nikkei to leave their homes on Terminal Island, near Los Angeles, but did not place the community in camps at that time. A week prior to the Bainbridge removal, a voluntary advanced party of Nikkei from Los Angeles began working at Manzanar. Harlan D. Unrau, The Evacuation and Relocation of Persons of Japanese Ancestry During World War II: A Historical Study of the Manzanar Relocation Center (United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1996).

- ↑ "Bainbridge Island before WWII," BIJAC History, http://www.bijac.org/index.php?p=HISTORYPreWWII .

- ↑ "Bainbridge Island before WWII," BIJAC History, http://www.bijac.org/index.php?p=HISTORYPreWWII .

- ↑ Junkoh Harui, interview by Donna Harui, 31 July 1998, Densho.

- ↑ Louis Fiset, Camp Harmony: Seattle's Japanese Americans and the Puyallup Assembly Center (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2009), 30.

- ↑ The Seattle Council of Churches released a "statement of comfort and good-will" to Islanders, but gave no aid. Report of the Meeting of the Social Welfare and Service Committee, 26 Mar 1942, Box 15/Fld 5, Church Council of Greater Seattle Records, Accession No. 1368-7, University of Washington Libraries.

- ↑ "Instructions to All Japanese Living on Bainbridge Island," 24 Mar 1942, "Bainbridge Island," Camp Harmony Exhibit, University of Washington Libraries, last revised 20 Dec 1999."

- ↑ Tom G. Rathbone, Report of Service and Control Station, Bainbridge Island Japanese Evacuation, undated, "Bainbridge Island," Camp Harmony Exhibit, University of Washington Libraries, last revised 20 Dec 1999.

- ↑ Joseph Conard (American Friends Service Committee), Japanese Evacuation Report #5, 2 Apr 1942, "Bainbridge Island," Camp Harmony Exhibit, University of Washington Libraries, last revised 20 Dec 1999.

- ↑ "Exclusion and Internment," BIJAC History, http://www.bijac.org/index.php?p=HISTORYExclusionInternment .

- ↑ Nobuko Omoto, interview by Joyce Nishimura, 22 Oct 2006, Bainbridge Island Japanese American Community Collection, Densho.

- ↑ Conard, Japanese Evacuation Report #5.

- ↑ "Exclusion and Internment," BIJAC History, http://www.bijac.org/index.php?p=HISTORYExclusionInternment .

- ↑ Tats Kojima, interview by Debra Grindeland, 22 Oct 2006, Bainbridge Island Japanese American Community Collection, Densho.

- ↑ Andrews to E.R. Fryer, 20 Jan 1943, Box 4/Fld 28, Emery E. Andrews Papers, Accession No. 1908-001, University of Washington Libraries. Paul Ohtaki, "'Orientals' Shun Island Japanese," Bainbridge Island Review , 9 Apr 1942.

- ↑ "177 Former Bainbridge People Here," Minidoka Irrigator , 27 Feb 1943, 1.

- ↑ "Exclusion and Internment," BIJAC History, http://www.bijac.org/index.php?p=HISTORYExclusionInternment .

- ↑ Ohtaki, "No Islander Implicated in Jap Riot," Bainbridge Island Review , 17 Dec 1942.

- ↑ Mary Woodward, In Defense of Our Neighbors , 87.

- ↑ Woodard, In Defense of Our Neighbors , 129-143.

- ↑ Woodward, In Defense of Our Neighbors , 115.

- ↑ "History of the Japanese-American Internment Memorial," Pritchard Park.

Last updated April 30, 2024, 5:58 p.m..

Media

Media