Chick sexing

From the 1930s until the 1950s, chick sexing became one of the most accessible professions for Japanese Americans. Although several techniques for sorting chicks by sex date to the beginning of the 20th century, Issei immigrants introduced new techniques that transformed the chick sexing industry into a viable employment opportunity for Japanese Americans. By 1942, Japanese Americans dominated the chick sexing industry, and, despite the consequences of the incarceration, continued to market the success of Japanese American chick sexers towards farmers across the United States.

Background

Originally developed by Tokyo University veterinary scientists in 1925, the "vent" method of identifying and sorting baby chicks by gender was brought to the United States sometime in 1934. As scholar Eiichiro Azuma states in his article "Race, Citizenship, and the 'Science of Chick Sexing,'" many Issei community leaders still looked to agriculture as a medium for economic advancement despite racially discriminatory laws such as the Alien Land Act . [1] As a result, the Issei encouraged their Nisei children to seek out employment in a variety of fields of agricultural work, with chick sexing being among the most popular. Over the course of the late 1930s, as Azuma notes, the Nisei adoption of the Tokyo University method helped accelerate the credibility of Nisei chick sexers as both capable workers and as knowledgeable of what came to be seen as a "Japanese method." [2] By 1937, the International Baby Chick Association—the leading trade organization for chick sexers—approved the Japanese vent method and regarded it as the premier technique in chick sexing. In 1937, Shigeru John Nitta opened the first chick sexing school in the United States. [3]

The monopolization of chick sexing by Japanese Americans both fed into and combated racial stereotypes of the period. Although Japanese Americans faced competition and exclusion in the West Coast agricultural industry, Japanese Americans found greater acceptance within the trade of chick sexing. Azuma argues that many Nisei embraced their identity as Japanese Americans towards marketing their skills as talented chick sexers, even to the point of accepting racial stereotypes. Many Japanese American leaders defaulted on Western stereotypes of Japanese, such as having small hands and possessing an efficient and disciplined work ethic, as a means of monopolizing control over the industry.

Wartime Setbacks

The incarceration of Japanese Americans had a deep impact on the West Coast chick sexing industry. Even before the forced removal of Japanese Americans, California poultry farmers pleaded with the state government to replace their Japanese American chick sexers. On February 19, 1942, a California state official warned the Department of Agriculture that the forced removal of Japanese chick sexers would disrupt poultry production, and suggested allowing Nisei sexers to stay until the completion of the work in Spring 1942. [4] California state agricultural officials assured farmers that they were in the process of finding white replacements, and cited the hatcheries of Petaluma, California, as a successful example of white chick sexers. While the state government reached out to several universities, such as the University of California, with the intent of establishing a training program, agricultural experts warned that replacement sexers could not be trained in time for the Spring 1942 season.

Immediately following Executive Order 9066 , hundreds of Nisei chick sexers left the West Coast exclusion zone for seasonal work in the Midwest and East. Sexers faced constant harassment while traveling to new job sites; Azuma notes that the FBI tracked the movement of Nisei sexers who might be engaged in what they called a "possible Japanese courier system," and local police in several midwestern towns frequently arrested sexers and questioned their motives.

Yet sexers continued to move east, and received employment opportunities due to labor shortages and the characterization of chick sexing as a "Japanese trade." In December 1942, the U.S. Department of Agriculture issued a bulletin to poultry farmers across the country encouraging the employment of Nisei chick sexers as part of the greater seasonal leave program:

Some hatcherymen are uncertain whether they may properly use American-born Japanese chick sexers. Use of American-born Japanese is wholly proper in all parts of the United States except the restricted zones set up by the military authorities. American-born Japanese are encouraged to seek employment outside the relocation centers. Every one of them is thoroughly investigated before being permitted to accept employment. [5]

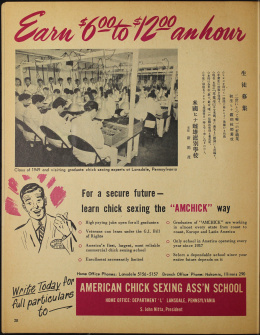

Following the War Relocation Authority 's distribution of loyalty questionnaires in February 1943 and the establishment of a leave clearance program, more Nisei found employment as chick sexers throughout the Midwest, East, and South. In Chicago, resettlers George and Ann Sugano established in 1947 the National Chick Sexing Association and School, a training center to help Japanese Americans to become chick sexers and find employment with hatcheries. [6] Several groups, including the International Chick Sexing Association, applauded the work of Nisei chick sexers and vouched for their loyalty as hardworking Americans dedicated to the war effort. In the July 1950 issue of Scene magazine, an article profiled the accomplishments of chick sexing pioneer Shigeru John Nitta and praised the field as a source of employment for Japanese Americans. [7]

Postwar Changes

After the termination of the army's exclusion policy of Japanese Americans from the West Coast, Japanese Americans returned to the West Coast and re-entered the western chick sexing industry. Even as prejudice against Japanese Americans decreased from their wartime levels, Japanese Americans continued to embrace the racial stereotypes associated with chick sexing. Azuma argues that Japanese American chick sexers transformed the image of chick sexing from a menial task into a "scientific" process that required dedication and discipline. Yet it is because chick sexing functioned as part of the agricultural production chain, Azuma concludes, that white Americans accepted Japanese American chick sexers as skilled farm workers, distinguished from more manual forms of farm work. Yet as Japanese Americans chick sexers asserted their Japanese identity as an important part of the profession, most Nisei excluded postwar Japanese immigrants from the profession. Despite the irony of their previous experiences with nativism in 1942, some Nisei went so far as to claim their American identity as a similar credential for entering the industry. [8]

By the 1950s, the number of Japanese American chick sexers began to decline. Unions, such as the AFL-CIO, pushed Japanese American chick sexing groups to include other racial groups in the industry. With the increase of Korean and Mexican immigrants accepting sexing jobs and the lack of Sansei willing to enter the profession, by 1970 Japanese Americans disappeared from the chick sexing industry.

Legacies

The story of Japanese American chick sexers remains an important chapter in the history of Japanese Americans in agriculture. In August 1996, following the death of chick sexing pioneer John Nitta, journalist Takeshi Nakayama penned an article for the Rafu Shimpo outlining Nitta's work and the legacy of Nisei chick sexers. In popular culture, several works on Japanese Americans include mentions of chick sexing. Author Cynthia Kadohata incorporates chick sexing into several of her novels. In The Floating World, the parents of the protagonists work as migrant chick sexers in the South, further accentuating the sense of dislocation experienced by the family during the war years. Kadohata's 2004 novel Kira-Kira centers on a Japanese American family living in 1950s Georgia, with both parents taking work as chick sexers at a hatchery following the loss of their store in Iowa.

For Further Information

Azuma, Eiichiro. "Race, Citizenship, and the 'Science of Chick Sexing': The Politics of Racial Identity among Japanese Americans." Pacific Historical Review 78.lakers2 (2009): 242–75.

Kadohata, Cynthia. The Floating World. New York: Ballantine Books, 1989.

———. Kira-Kira. New York: Athenaeum Books, 2004.

Lunn, John H. "CHICK SEXING." American Scientist 36.2 (1948): 280–87.

Yokota, Ryan. " Japanese American Chick Sexers in Chicago - Part 1. " Discover Nikkei, September 28, 2016.

Yokota, Ryan. " Japanese American Chick Sexers in Chicago - Part 2. " Discover Nikkei, September 29, 2016.

Footnotes

- ↑ Eiichiro Azuma, "Race, Citizenship, and the 'Science of Chick Sexing': The Politics of Racial Identity among Japanese Americans," Pacific Historical Review 78.2 (2009), 243.

- ↑ Azuma, "Race, Citizenship, and the 'Science of Chick Sexing,'" 245.

- ↑ "He Opened a New Field," Scene Magazine, July 1950, pg. 24-25, https://downloads.densho.org/ddr-densho-266/ddr-densho-266-20-mezzanine-3f2c44166e.pdf?_ga=2.10933748.1936702137.1661206506-709207601.1660439273

- ↑ "Administration Office Files, 1940-1942," F3741:2433, California Department of Agriculture Records, California State Archive.

- ↑ F. Y. Hirayama, "A Discussion dealing with Japanese Chick Sexors," Hatchery Tribune, (Jan. 1943), 12.

- ↑ Ryan Yokota, "Japanese American Chick Sexers in Chicago - Part 1," Discover Nikkei, September 28, 2016, http://www.discovernikkei.org/en/journal/2016/9/28/chick-sexers-1/ .

- ↑ "He Opened a New Field."

- ↑ Azuma, "Race, Citizenship, and the 'Science of Chick Sexing,'" 268-272.

Last updated Dec. 14, 2023, 5:36 p.m..

Media

Media