Dorothea Lange

| Name | Dorothea Lange |

|---|---|

| Born | May 26 1895 |

| Died | October 11 1965 |

| Birth Location | Hoboken, NJ |

Acclaimed documentary photographer. Dorothea Lange (1895–1965) is one of the most important photographers of the twentieth century. The immense body of work she produced beginning in the early 1930s with "White Angel Breadline" (1933) and continuing until her death three decades later was ambitious and path breaking. Her photographs of the Great Depression set the standard for the photographic document. Following her well-known images of migrant families, she photographed the forced removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans in 1942. She traveled throughout northern California during the spring and summer and photographed neighborhoods as Japanese Americans prepared to leave, several "assembly centers," and the Manzanar incarceration camp.

Before the War

Dorothea Nutzhorn was born in Hoboken, New Jersey, just before the turn of the twentieth century. Her childhood was marked by two life-altering events: a bout of polio that left her with a limp, and the separation of her parents. Nutzhorn finished high school, dropped out of a teachers college, and took up the camera, learning from New York photographers including Arnold Genthe and Clarence White. In 1918 she moved from New York to San Francisco, interrupting an around-the world-trip. With her photographic training, Dorothea found a job at a department store camera counter, changed her name to Lange (her mother's maiden name), joined the San Francisco Camera Club, and soon after opened her own studio. She transformed the studio into a salon, and Lange became the most sought after portraitist in the city. Her business acumen allowed her to support her young family and her first husband, the painter Maynard Dixon. This marriage fell apart after Lange met Paul Taylor, a social scientist who used photography in his work. Lange's major projects include the book she co-authored with Taylor, An American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion (1939).

With the crisis of the Depression, Lange turned her talents from the moneyed to the dispossessed as she began to focus on the social unrest that accompanied rampant unemployment. Lange began her work as a documentary photographer for the federal government of the United States in 1935. [1] For the first two years of her government employment, she worked as a salaried "Photographer-Investigator" for Roy Stryker, the chief of the photography department of the Resettlement Administration (RA). After a ten-month hiatus from government work, Lange was rehired from October 1938 until January 2, 1941, by the RA, which had been renamed as the Farm Security Administration. [2] During her government tenure, she produced some of the best-known documentary photographs ever made including "Migrant Mother," which was in Roy Stryker's view the "quintessential" photograph of the period.

Lange Photographs Japanese American Incarceration

Photographers working under the auspices of the War Relocation Authority made thousands of photographs of the forced removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans between 1942 and 1945. [3] During the spring of 1942, as Japanese Americans were forced to leave their homes and businesses, Lange photographed the exclusion process as she traveled between Fresno and Sacramento. These photographs have been analyzed by a number of scholars, and many are easily accessible via the United States National Archives and Records Administration's website.

How Lange came to work in the position of "Photographer" for the WRA remains unclear. [4] In an interview conducted thirty years after Lange's involvement with the WRA, Taylor, Lange's husband, recalled the vague circumstances of her employment: "I had done work for the Social Security Board. We knew the regional director very well. He had on his staff an information man, who shifted over and became the information man for the War Relocation. So when they wanted a photographer, he knew Dorothea and me, knew her work and got her onto his staff." [5]

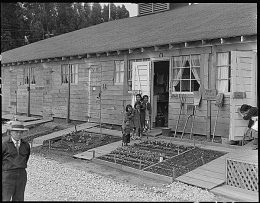

Lange began to photograph the forced removal at the end of March 1942 and over four months produced hundreds of images. The job description for Photographer makes it clear that although general assignments were given, a great deal of the responsibility for choosing subject matter fell to the individual photographers. Lange traveled to family farms in small California towns, including Centerville and Lodi, where she made images of families grouped in such a way as to resemble formal portraits with parents and children in front of the family house. [6] In addition to more formally posed portraits, Lange photographed Japanese American families at work tending their fields. [7]

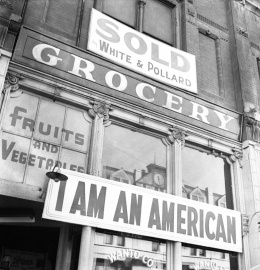

Once Japanese Americans left their homes, farms, and businesses, Lange focused on the material aspects of the forced removal itself, including piles of luggage on curbsides, lines of Japanese Americans with tags dangling from their coats, and busses readied for boarding. Lange continued to use strategies of representation she began to develop with her FSA photography, including the appropriation of signs that commented both on the process of the exclusion and the conditions that made it possible. Lange frequently photographed posted texts: evacuation orders, billboards, and newspaper headlines. In urban settings, she photographed store windows that advertised clearance sales.

A photograph Lange made in Oakland in April 1942 of a storefront was captioned, "Following evacuation order, this store, at 13th and Franklin Streets, was closed. The owner, a University of California graduate of Japanese descent, placed the 'I AM AN AMERICAN' sign on the store on December 8, the day after Pearl Harbor." When recalling another photograph of a billboard that read, "It takes 8 Tons to K.O. One Jap," Lange remarked: "In 1942, I worked for the War Relocation Authority. I photographed the billboards that were up at the time. Savage, savage billboards. I photographed the evacuation of the Japanese, the Japanese Americans from the Bay Area. I photographed their arrival in the assembly centers. And then they were moved again, into the interior." [8] Although the inclusion of signs within Lange's photographs may have been a way to critique the implementation of Executive Order 9066, caption writers for the WRA generally avoided calling attention to any detail in the image that might place the government in a negative light.

Lange photographed the Sacramento , Salinas , Stockton , Turlock , and Tanforan Assembly Centers as Japanese Americans moved in. She arrived at Tanforan in San Bruno just after it opened. Her photographs there depicted meager conditions and monotony including horse stalls converted into barracks, open sewers, long lines at lunchtime, and people without much to do. At Manzanar, Lange photographed broad views of the camp as well as intimate shots of families. She also focused her camera on the incarcerated at work and at leisure: making camouflage nets; clearing brush; tending gardens; cooling off in a stream; and engaging in art class.

Because Lange often called attention to the injustice of the incarceration, the WRA never released most of her photographs. Although Lange's FSA images were well known, the WRA kept the vast majority of Lange's incarceration photographs from public view. [9] In letters written after she concluded her work for the WRA, Lange acknowledged her disappointment that her photographs did nothing significant in her view to help Japanese Americans. [10] She channeled this distress into encouragement of her friend Ansel Adams and his independent project to photograph Manzanar. On November 12, 1943 Lange wrote to Adams: "I fear the intolerance and prejudice is constantly growing. We have a disease. It's Jap-baiting and hatred. You have a job on your hands to do to make a dent in it—but I don't know a more challenging nor more important one. I went through an experience I'll never forget when I was working on it and learned a lot, even if I accomplished nothing." [11] Although Lange continued to offer her support while Adams worked on his project, later in life she voiced her dissatisfaction with his photographs of the incarceration as well. [12]

Subsequent Career

Dorothea Lange led a remarkable life that pushed at the constraints of gender in the pre and post-World War II eras. The balance she attempted between the different roles of wife, mother, and artist led to strain and sometimes outright conflict. [13] She created some of the most famous photographs in American visual culture, but toward the end of her life was insecure about her artistic legacy. After Lange finished her work for the WRA in 1942 and Office of War Information in 1945, she created new assignments including essays for LIFE magazine, many of which failed, and assisted Edward Steichen with the 1955 Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) blockbuster "The Family of Man." Her health began its downward spiral leaving her hospitalized and in pain for a good part of her final years. Lange's solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York opened just after she died in 1965.

For More Information

Archival Sources

Dorothea Lange Archive. The Oakland Museum of California. Oakland, CA.

Dorothea Lange Papers. Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley.

National Archives II. College Park, Md. Record Group 210—Still Pictures Branch. http://www.archives.gov/research/arc/topics/japanese-americans/

Lange, Dorothea. "The Making of a Documentary Photographer." Interview by Suzanne B. Reiss. Regional Oral History Project. Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley.

Books and Articles

Alinder, Jasmine. Moving Images: Photography and the Japanese American Incarceration . Chicago and Urbana: The University of Illinois Press, 2009.

Conrat, Maisie and Richard Conrat. Executive Order 9066 . Los Angeles: California Historical Society, 1972.

Creef, Elena Tajima. Imaging Japanese America: The Visual Construction of Citizenship, Nation and the Body . New York: New York University Press, 2004.

Daniels, Roger. "Dorothea Lange and the War Relocation Authority." In Dorothea Lange: A Visual Life . Ed. Elizabeth Partridge. 44-55. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994.

Davidov, Judith Fryer. "'The Color of My Skin, the Shape of My Eyes': Photographs of Japanese-American Internment by Dorothea Lange, Ansel Adams and Toyo Miyatake." The Yale Journal of Criticism 9.2 (1996): 223-44.

Goggans, Jan. California on the Breadlines: Dorothea Lange, Paul Taylor and the Making of a New Deal Narrative . Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010.

Gordon, Linda and Gary Y. Okihiro, eds. Impounded. Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment . New York: W.W. Norton, 2006.

Gordon, Linda. Dorothea Lange: A Life Beyond Limits . New York: W.W. Norton, 2009.

Ohrn, Karin Becker. Dorothea Lange and the Documentary Tradition . Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University, 1980.

Online Resources

"Dorothea Lange Gallery," Manzanar National Historic Site, National Park Service. http://www.nps.gov/manz/photosmultimedia/Dorothea-Lange-Gallery-Gallery.htm

"Dorothea Lange and the Relocation of the Japanese," Online Exhibition, The Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco. http://www.sfmuseum.org/hist/lange.html

"Dorothea Lange and the Relocation of Japanese Americans," Online curriculum for middle-high school students. Linda Harris and J Paul Getty Museum Education Staff, Los Angeles, CA. http://www.getty.edu/education/teachers/classroom_resources/curricula/dorothea_lange/lange_lesson04.html

"Looking and Telling: Picturing History: The Internment." Picture This: California Perspectives on American History . Online educational resource. Oakland Museum of California. http://museumca.org/picturethis/looking-telling-picturing-history-internment

Matsumoto, Nancy. "Documentary Manzanar (Dorothea Lange)." December 12, 2011. Discover Nikkei. http://www.discovernikkei.org/en/journal/article/3816/

"San Francisco Evacuation, Tanforan Assembly Center, and Manzanar Relocation Center Photographs." Power Point presentations available online. The Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco. http://www.sfmuseum.org/hist8/ppoint.html

"Women Come to the Front: Journalists, Broadcasters and Photographers during World War II." Online Exhibition, Library of Congress. http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/wcf/wcf0013.html

Footnotes

- ↑ See Jan Goggans, California on the Breadlines: Dorothea Lange, Paul Taylor and the Making of a New Deal Narrative (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010).

- ↑ Memo to Dorothea Lange from the U.S. Dept of Agriculture, Farm Security Administration, 11 December 1941, Dorothea Lange Archive, Oakland Museum of California.

- ↑ In addition to five motion pictures and two-dozen sound recordings, Record Group 210 "Records of the War Relocation Authority," contains approximately 15,000 still photographs. See "Reference Information Paper 70: A Finding Aid to Audiovisual Records in the National Archives of the United States Relating to World War II," http://www.archives.gov/publications/ref-info-papers/70/part-3.html#rg210 .

- ↑ Roger Daniels suspected that Lange might have been employed directly by Milton Eisenhower, who spent time in the Bay Area while head of the WRA. Daniels, "Dorothea Lange," 50.

- ↑ Paul Schuster Taylor, "California Social Scientist," personal interview conducted by Suzanne B. Riess, , pp. 228-229, 1973, Earl Warren History Project, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

- ↑ Dorothea Lange, 1A-60, RG 210, Still Pictures Branch, National Archives II, College Park, MD.

- ↑ Dorothea Lange, 1A-59, RG 210, Still Pictures Branch, National Archives II, College Park, MD.

- ↑ Quoted in Partridge, ed., Dorothea Lange , 118.

- ↑ Linda Gordon, "Dorothea Lange Photographs the Japanese American Internment," in Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment , eds. Linda Gordon and Gary Okihiro (New York: W.W. Norton, 2006), 5.

- ↑ The WRA dismissed Lange "without prejudice" on July 30, 1942 with the remark "completion of work." Dorothea Lange Papers, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

- ↑ Dorothea Lange, letter to Ansel Adams, 12 November 1943, Box 2, Collection 696 (Ansel Adams Papers), Department of Special Collections, University Research Library, University of California Los Angeles.

- ↑ Dorothea Lange, "The Making of a Documentary Photographer," personal interview conducted by Suzanne B. Reiss, Regional Oral History Project, Bancroft Library, University of California/Berkeley, 1968, 190-191, 200-201.

- ↑ Linda Gordon, Dorothea Lange: A Life Beyond Limits (New York, NY: W.W. Norton, 2009).

Last updated July 6, 2020, 4:12 p.m..

Media

Media