Final Report, Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 (book)

| Title | Final Report, Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 |

|---|---|

| Author |

Report issued under the name of General

John L. DeWitt

that provided a detailed and highly favorable account of the army's actions in removing Japanese Americans from the West Coast. The report became a key factor in the legal challenges to exclusion and resulted in both intra- and inter-departmental conflicts within the Justice and War Departments. Research in the 1980s revealed that the report had been doctored prior to the court cases, and this revelation was the basis for the reopening of the cases under the writ of error

coram nobis

.

The Original Report

The report was produced by the staff of the Civil Affairs Division of the Western Defense Command led by Karl Bendetsen in early 1943. The 618-page document includes the rationale for the "evacuation program," a detailed summary of its logistics, scores of charts and tables, and dozens of photographs. It was first printed in April of 1943.

Assistant Secretary of War John McCloy received the report on April 19, along with a cover letter signed by DeWitt dated April 15 that noted the report might be useful for the pending legal challenges. McCloy began to read the report and was alarmed by two items. The first was a section of the foreword where DeWitt stated his opposition to Japanese Americans returning to the West Coast for the duration of the war, which ran counter to McCloy's own sentiments and that of the War Relocation Authority and many others in the administration.

Even more serious was a paragraph from chapter 2, "Need for Military Control and for Evacuation." First, there was the assertion that it was "impossible to establish the identity of the loyal and the disloyal with any degree of safety." The next sentence read: "It was not that there was insufficient time in which to make such a determination; it was simply a matter of facing the realities that a positive determination could not be made, that an exact separation of the 'sheep from the goats' was unfeasible." [1] This text was problematic to McCloy because it undermined prior War Department claims that there had not been sufficient time for hearings. The text also could be viewed as overtly racist by the court.

McCloy called Bendetsen in San Francisco that night and scolded him for having the report printed before circulating it. "The suggestion that military necessity is going to require for the duration that every Japanese be kept out of there, they're going to laugh at that," McCloy told Bendetsen. "[The court would] be disposed to think that the original determination was not as sound as it might be." [2] Since only ten copies had been printed, McCloy had Bendetsen come to Washington to work with McCloy's deputy, John M. Hall, on revisions. When DeWitt got wind of this, he replied, "My report to Chief of Staff will not be changed in any respect whatsoever either in substance or form and I will not, repeat not, consent to any, repeat any, revision made over my signature." [3]

Bendetsen was subsequently able to convince DeWitt to accept inserting the claim that time was indeed a factor. John Hall crafted the revised sentences: "To complicate the situation no ready means existed for determining the loyal and the disloyal with any degree of safety. It was necessary to face the realities—a positive determination could not have been made." [4]

Hall and Bendetsen then tracked down all copies of the original report and cover letter. McCloy then had DeWitt send a second cover letter as if the first never existed; this was dated June 5, 1943. Every copy of the report and letter as well as proofs, drafts, and notes was burned. Even while being suppressed, the contents of the report were leaked to lawyers working for the West Coast states preparing an amicus brief for the coming Supreme Court cases challenging the forced removal and detention. The revised report was not released until January 1944.

Use in the Korematsu Case

When the report was finally released in January 1944, it came as a surprise to Justice Department lawyers who were preparing to defend the Korematsu case before the Supreme Court. (See Korematsu v. United States ) When the report hit the press, newspapers around the country highlighted the false claims of espionage it contained as well as supposed Justice Department failures. A Los Angeles Times editorial on the release of the report concluded that "The disclosures not only justify the original ouster of the Japanese population, but show why they should not be permitted to return, at least while the war lasts." [5]

Justice Department lawyers Edward Ennis and John Burling, who were working on the government's brief for the Korematsu case, were troubled by the allegations of shore-to-ship signaling from the West Coast and radio transmissions from the West Coast to Japanese submarines. Inquiries with the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) verified that both allegations were untrue and that DeWitt knew that they were untrue. In an April 13, 1944, memorandum, Burling wrote, "We are now therefore in possession of substantially incontrovertible evidence that the most important statements of fact advanced by General DeWitt to justify the evacuation and detention were incorrect, and furthermore that General DeWitt had cause to know, and in all probability did know, that they were incorrect at the time he embodied them in his final report to General Marshall." [6]

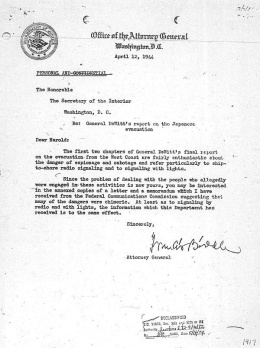

Burling and Ennis insisted on inserting a footnote into the report disavowing the claims, which led to internal conflict with Solicitor General Charles Fahy , who would be responsible for arguing the case before the Supreme Court. Predictably, McCloy and the War Department also objected to the footnote. Eventually, the parties agreed on a watered down footnote that removed the specifics of the complaint.

Coram Nobis Cases

In the early 1980s, legal scholar Peter Irons began looking at archival records on the wartime Supreme Court cases for a book. At the same time, Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga , a researcher for the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians , came across records indicating the existence of the earlier version of the Final Report and the chain of events that led to its being changed. Herzig-Yoshinaga also found evidence that, in the process of gathering all of the evidence of the earlier report to be destroyed, the tenth printed copy of the original report had never been found. In the fall of 1982, while waiting to meet with a National Archives archivist, she noticed a copy of the Final Report on a desk that had a different binding than the copies she had seen. Opening it, she discovered margin notes and realized "these were the corrections that were suggested by McCloy’s office." [7] The tenth copy of the original report provided both definitive proof that the report had been changed and key evidence in the subsequent coram nobis cases.

Find in the Digital Library of Japanese American Incarceration

Final Report, Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942

This item has been made freely available in the Digital Library of Japanese American Incarceration , a collaborative project with Internet Archive .

For More Information

Dewitt, John L. Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 . Washington D.C.: U.S. Govt. Print. Off., 1943.

Fujita-Rony, Thomas Y. "'Destructive Force': Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga's Gendered Labor in the Japanese American Redress Movement." Frontiers 24.1 (2003): 38–60.

Higa, Karin, and Tim B. Wride. "Manzanar Inside and Out: Photo Documentation of the Japanese Wartime Incarceration." In Reading California: Art, Image, and Identity, 1900–2000 . Edited by Stephanie Barron, Sheri Bernstein, and Ilene Susan Fort. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000. 314–37. [Includes an analysis of the photographic section of the report.]

Irons, Peter. Justice at War: The Story of the Japanese American Internment Cases . New York: Oxford University Press, 1983.

de Nevers, Klancy Clark. The Colonel and the Pacifist: Karl Bendetsen, Perry Saito and the Incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II . Forward by Roger Daniels. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2004.

Yamamoto, Eric, Margaret Chon, Carol L. Izumi, Jerry Kang, and Frank H. Wu. Race, Rights, and Reparation: Law and the Japanese American Internment . Gaithersburg, Md.: Aspen Law & Business, 2001.

Footnotes

- ↑ Peter Irons, Justice at War: The Story of the Japanese American Internment Cases (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983), 208.

- ↑ Klancy Clark de Nevers, The Colonel and the Pacifist: Karl Bendetsen, Perry Saito and the Incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2004), 215.

- ↑ Irons, Justice at War , 209.

- ↑ Irons, Justice at War , 210.

- ↑ Irons , Justice at War , 279.

- ↑ Irons, Justice at War , 285.

- ↑ Thomas Y. Fujita-Rony "'Destructive Force': Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga's Gendered Labor in the Japanese American Redress Movement," Frontiers 24.1 (2003): 50.

Last updated Jan. 9, 2024, 3:47 a.m..

Media

Media