Fort Lincoln (Bismarck) (detention facility)

| US Gov Name | Fort Lincoln Internment Camp |

|---|---|

| Facility Type | Department of Justice Internment Camp |

| Administrative Agency | U.S. Department of Justice |

| Location | Bismarck, North Dakota (46.8000 lat, -100.7833 lng) |

| Date Opened | December 7, 1941 |

| Date Closed | March 6, 1946 |

| Population Description | Held Japanese and German nationals; German and Italian seamen; and Japanese American "renunciants," those who had given up their U.S. citizenship. |

| General Description | Located in Burleigh County, south of Bismarck, North Dakota |

| Peak Population | 1,518 (1942-02-01) |

| National Park Service Info | |

Located on a former military post and CCC camp outside of Bismarck, North Dakota, the Fort Lincoln internment camp held a total of 3,850 internees of German and Japanese descent. There were two distinct groups of Japanese American internees. The first consisted of over 1,100

Issei

community leaders from the West Coast who arrived in February 1942 before being transferred to other camps later that summer and fall. Three years later, in February 1945, the second group arrived, consisting of over 750 inmates who were thought to be fomenting unrest at

Tule Lake

. Most were young

Nisei

who had renounced their American citizenship. Most sailed for Japan at the end of 1945, while others were transferred to

Santa Fe

. The camp closed on March 6, 1946. The site is now part of the campus of United Tribes Technical College.

Origins/Layout/Environmental Conditions

The INS detention facility at Fort Lincoln was converted from a former military outpost turned CCC camp that was located south of the heavily German American town of Bismarck, in Burleigh County, North Dakota. Built to replace an earlier Fort Lincoln that had been decommissioned in 1891, construction took place from 1899 to 1902. Historian and archivist Frank Vyzralek described it "as a pork barrel military post" that served as "a convenient means of funneling federal money into the states for the benefit of local and regional merchants and businessmen." Used to assemble troops during World War I and as a training camp in the 1920s, it became the state CCC headquarters in 1933. When the INS took over the facility in 1941, additional wooden barracks along with a mess hall and other buildings were added. [1]

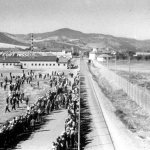

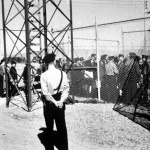

POWs and internees were housed in three two-story red brick barracks along with the wooden barracks buildings. The brick buildings were subdivided into smaller, dormitory-like rooms. Both types of barracks were equipped with steel cots, at least some of which were double decked. The camp was surrounded by a ten-foot cyclone fence. After a number of escape attempts, three-strand barbed wire was added to the top of the fence, along with seven watch towers, each equipped with flood lights and a rifle. The German and Japanese compounds were separately fenced and separated by a ten-foot lane. A single mess hall served the prisoners, though it was divided into two wings and had two kitchens, one that produced a diet palatable for the Germans, the other for the Japanese. Prisoners arrived in Bismarck by train and were transported the remaining distance to the camp by truck. [2]

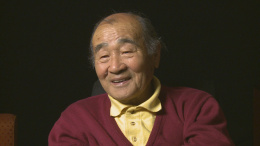

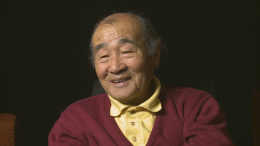

By the time the second group of Japanese American internees arrived at Fort Lincoln in 1945, other amenities had been added leading Fort Lincoln chronicler John Christgau to call it "a huge improvement over Tule Lake." Barracks were heated by gas heaters and rooms in the main brick dormitory buildings had their own showers. Allowed to intermingle with the German prisoners, the Nisei renunciants were allowed to use the Germans' Kasino, which sold beer and wine. There was also a theater, indoor pool, skating rink, and even a ski jump. A prisoner-run bakery provided fresh bread daily for the mess hall. In a 2010 interview, former Fort Lincoln internee Hitoshi "Hank" Naito recalled, "my impression of Fort Lincoln was much better than Tule Lake or Heart Mountain or Santa Anita." He went on to say, "... we were sarcastically remarking, living here in Bismarck, it seemed like being an 'enemy alien,' you get a better treatment than being Americans." [3]

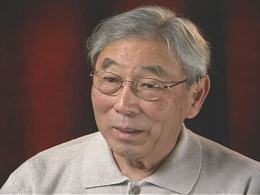

The prisoners nonetheless had to deal with difficult environmental conditions. "Icicles more than six feet long hung from the roofs," wrote Bunyu Fujimura in his memoir. The twenty new wood frame barracks—each with the capacity to house forty-two men—were purchased from Alabama and lacked insulation and even with modifications, provided little protection from the cold. Blizzards could last for days, with snow piling as high as the eaves of the barracks. "Snow piled up in the front door, you can't get out," remembered Charles Oihe Hamasaki. "That's how cold it was." [4]

Internee Population

There were two separate populations of Japanese American internees as well as German crews of ships seized in U.S. ports and resident German enemy alien internees. The very first prisoners at Fort Lincoln were 220 German seamen who arrived on May 31, 1941. The U.S. had detained crews from German ships docked in the U.S. since after the German attack on Poland in 1939, most of them at Ellis Island. More German seamen arrived after this initial group, and on December 20, 110 German enemy aliens arrived, most from the West Coast, bringing the population of Fort Lincoln to 410. [5]

The first group of Japanese American internees consisted of over 1,100 Issei who arrived at Fort Lincoln in two groups in February of 1942: 415 from the West Coast arrived on February 9 and 715 more on February 26. Most of these men were immigrant community leaders—Buddhist priests, Japanese language school teachers, newspaper editors, and heads of Japanese immigrant economic or cultural organizations—who were arrested after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor but before the mass roundup of all Japanese Americans on the West Coast. Most came via short-term detention stations such as Tuna Canyon, Griffith Park, or San Pedro. Enemy Alien Hearing Boards convened at Ft. Lincoln in February for the German internees, most of whom were released or paroled afterwards. Hearings for the Japanese internees were marred by conflict between Korean immigrant translators and internees and resulted in three Issei requiring medical attention. Complaints to the Spanish consul resulted in an internal investigation by the INS that found that Issei had been unjustly abused and resulted in the dismissal of two interpreters and the suspension of three INS inspectors. Issei whom the boards "released" were allowed to rejoin their families at "assembly centers" or War Relocation Authority camps in the summer and fall of 1942; those ordered interned were transferred to army-run internment camps such as Lordsburg . By October 1942, nearly all of the Japanese and German internees had moved on, leaving just three hundred or so German seamen. As part of the general movement of enemy aliens from army run camps back to INS run camps in order to make room for the growing numbers of POWs, over 1,000 German enemy aliens moved to Ft. Lincoln starting in March 1943, joining the remaining German seamen and pushing the camp's population to over 1,500. [6]

The second group of Japanese Americans at Ft. Lincoln arrived in early 1945 and were mostly young Nisei and Kibei who had been incarcerated at Tule Lake. This younger group were among the 5,400 at Tule Lake who, under duress, renounced their U.S. citizenship, enabling the Department of Justice to intern them in DOJ camps as “enemy aliens” and to deport them. Reasons for renouncing varied, ranging from anger and protest against the country that imprisoned them, to fear of being forcibly relocated again without a job or housing or community support while the war with Japan raged on. While an initial group identified as leaders of community resistance in Tule Lake were sent to Santa Fe, there was not enough room there to accommodate all. With the numbers of German enemy alien internees and German seamen down to about 700, less than half of the peak, there was room at Fort Lincoln. As a result, about 650 were transferred from Tule Lake on February 10, arriving at Ft. Lincoln on February 14. One hundred more renunciants were transferred from Tule Lake to Ft. Lincoln in July 1945. The U.S. prepared to deport two-thirds of this group in November and December 1945; however, many had changed their minds about renouncing and going to Japan. With the aid of lawyer Wayne Collins, most were able to avoid deportation and to eventually recover their U.S. citizenship. The last of the German internees were sent to Ellis Island in February 1946. The last to leave were 200 of the Tule Lake group, who left on March 6 for Santa Fe. In total, 3,850 internees passed through Ft. Lincoln. [7]

Internee Life at Ft. Lincoln

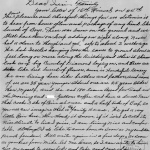

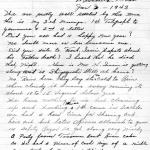

Internee life at Ft. Lincoln for the 1942 Issei group seemed to be similar to that found at other enemy alien internment sites. In his diary, Toyojiro Suzuki, a soon-to-be thirty-nine-year-old Issei fisherman from Terminal Island, California, wrote of his work in the mess hall kitchen, his letter writing, and various forms of recreation that included movies, softball games, and various crafts. But much of his diary records the boredom of his incarceration. "Boredom everywhere," he wrote on February 23, two weeks after his arrival. "Each day seems to be a dull repetition of the previous day," he wrote on July 26. In addition to kitchen work, Suzuki did various other kinds of work around the camp for which he was paid. But Los Angeles businessman Mitushiko H. Shimizu recalled that other older Issei internees were not used to doing such physical labor. Inmates did their best to establish normal Japanese community life in incarceration, organizing sumo tournaments and putting on shows that features Japanese folk songs and dances. Rev. Bunyu Fujimura recalled the Buddhist priests improvising a hanamatsuri commemoration, with one carving an image of Buddha out of a carrot. Internees made flowers out of paper in order to hold a funeral. There was some limited interaction with the Germans, including playing softball games with them. [8]

As noted above, the 1945–46 group from Tule Lake found the Ft. Lincoln facilities a vast improvement over Tule Lake. The internees resumed their early morning chanting and exercises, which were allowed by the administration; however, after German internee complained about the noise, the exercises were moved indoors. The internees started Japanese language and culture classes in March 1945. There was softball in the warmer months, ice skating in the winter, and an indoor swimming pool. "We couldn't believe it at first," remembered Hitoshi "Hank" Naito. "'You mean to tell me we can swim in there?'" There was also greater interaction with the German internees who willingly showed the newcomers the ropes. According to Christgau, "[s]oon the Japanese and Germans found themselves socializing regularly in the evenings in the German "Kasino," discussing the war news, exchanging personal stories, and sharing the bitterness of internment." [9]

Administration and Closing

The officer-in-charge at Fort Lincoln for most of the camp's life was I. P. "Ike" McCoy, who replaced A. S. Hudson early in 1942, at about the time the first group of Issei internees arrived. His top deputies were Charlie Lovejoy, who headed the surveillance division, responsible for the perimeter of the camp and for manning the guard towers, and Will Robbins, who headed internal security and governance, assisted by Edwin J. "Red" Selland. Eight guards, most of them locals, patrolled the camp's interior. McCoy presided over a number of crises at the camp involving the German internees and seamen in 1943–44 including a semi-mutiny over his imprisonment of seven pro-Nazi troublemakers in September 1943, the escape of an internee who was among a group doing railroad work outside the camp in November, and the discovery of an elaborate escape tunnel dug by two German internees in 1944. G. P. Lipp, a local physician, was under contract to provide medical services, but inmate doctors performed much of the routine work. [10]

McCoy was still in charge when the Tule Lake group arrived in February 1945. In August 1945, he was promoted. Bill Cook, the assistant officer-in-charge, took over the top spot. The twenty-seven-year-old Cook presided during the rest of the camp's life and oversaw its closing. [11]

After Fort Lincoln closed as an internment camp on March 6, 1946, it became a headquarters for the Garrison Division of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and served in the planning of the Garrison Dam on the Missouri River. INS equipment was transferred to nearby border control stations, while books from the library went to the Bismarck Public Library. The site was declared surplus property in 1964, setting off a state and community-wide discussion over its future use. In 1966–67 it became the Lewis and Clark Job Corps Training Center. In 1968, the leaders of North Dakota’s Native American tribes worked with local, state and federal officials to obtain the site as an Indian family training facility that was dedicated on Sept. 6, 1969. First named "United Tribes Employment Training Center," the former military post was transformed for the education and training of American Indian students and their families. The Center became the second tribal college to be established in the country and is now known as United Tribes Technical College (UTTC). The brick buildings of Fort Lincoln remain on site and have been repurposed for education and serve as classrooms and dormitories. Many of the fort's wood-frame buildings have been maintained and are still in use, though the wood barracks of the internment camp era were sold off in the 1960s. [12]

In 2003, an exhibition on the internment camp titled Snow Country Prison: Interned in North Dakota was organized by the North Dakota Museum of Art and UTTC and held at the UTTC campus on the site of the camp. It traveled to various other venues in 2004. The North Dakota Museum of Art brought the exhibition to its facility in Grand Forks in 2017. [13]

For More Information

Christgau, John. "Enemies": World War II Alien Internment . Ames: Iowa State University Press, 1985.

Kashima, Tetsuden. Judgment Without Trial: Japanese American Imprisonment during World War II . Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002.

" Site History, Fort Lincoln-United Tribes Site History. " United Tribes Technical College website.

Footnotes

- ↑ Frank E. Vyzralek, "The Alien Internment Camp at Fort Lincoln, North Dakota, during World War II: An Historical Sketch," unpublished manuscript, April 2003, 1–2; John Christgau, "Enemies": World War II Alien Internment (Ames: Iowa State University Press, 1985), 7, 30.

- ↑ Christgau, "Enemies," 7, 8, 20–30 passim, 74; Vyzralek, "The Alien Internment Camp at Fort Lincoln," 2; Bunyu Fujimura, Though I Be Crushed: The Wartime Experiences of a Buddhist Minister (Los Angeles: The Nembutsu Press, 1985), 62; Arthur Ogami Interview by Alice Ito, Segment 26, Seattle, Washington, March 10, 2004, Densho Visual History Collection, Densho Digital Repository, accessed on Apr. 20, 2020 at https://ddr.densho.org/media/ddr-densho-1000/ddr-densho-1000-154-transcript-321854c366.htm ; Hitoshi "Hank" Naito Interview by Tom Ikeda, Segment 23, Honolulu, Hawaii, June 11, 2010, Densho Visual History Collection, Densho Digital Repository, accessed on Apr. 20, 2020 at https://ddr.densho.org/media/ddr-densho-1000/ddr-densho-1000-286-transcript-ca9c6ca3c7.htm .

- ↑ Christgau, "Enemies" , 30, 161; Charles Oihe Hamasaki Interview by Martha Nakagawa (primary); Tom Ikeda (secondary), Segment 18, Culver City, California, February 24, 2010, Densho Visual History Collection, Densho Digital Repository, accessed on Apr. 20, 2020 at https://ddr.densho.org/media/ddr-densho-1000/ddr-densho-1000-274-transcript-6011fdc445.htm ; Hitoshi "Hank" Naito interview, Segments 23 and 24.

- ↑ Fujimura, Though I Be Crushed , 62; Christgau, "Enemies" , 39–40; Vyzralek, "The Alien Internment Camp at Fort Lincoln," 2; Charles Oihe Hamasaki interview, Segment 18.

- ↑ Christgau, "Enemies" , 8–9; 14–15; 25, 33, 59–60.

- ↑ Christgau, "Enemies" , 34–35, 37, 39, 63; Mitushiko H. Shimizu, interviewed by Mariko Yamashita and Paul F. Clark, Oct. 30, 1978, Courtesy of CSU Fullerton Center for Oral and Public History, Densho Digital Repository, accessed on Apr. 20, 2020 at http://ddr.densho.org/interviews/ddr-csujad-29-57-1/ ; Kango Kunitsugu, ed., Rohwer Reunion Booklet (Gardena, Calif.: First Rohwer Reunion Committee, 1990), 33; Tetsuden Kashima, Judgment Without Trial: Japanese American Imprisonment during World War II (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002), 109, 185, 186–87; Hyung-ju Ahn, Between Two Adversaries: Korean Interpreters at Japanese Alien Enemy Detention Centers during World War II (Fullerton: Oral History Program, California State University, Fullerton, 2002), 42–45; Stephen Mak, "'America's Other Internment': World War II and the Making of Modern Human Rights"(Ph.D. dissertation, Northwestern University, 2009), 147. Various War Relocation Authority and Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study documents record the steady trickle of internees arriving from Fort Lincoln at various camps from June to October 1942.

- ↑ Christgau, "Enemies" , 144–46, 161–62, 165, 170–76 passim; Kashima, Judgment Without Trial , 110;

- ↑ Toyojiro Suzuki Diary, translated by JY, March 1982, State Historical Society of North Dakota, accessed on July 20, 2020 at https://www.history.nd.gov/textbook/suzuki_diary_all.pdf ; Mitushiko H. Shimizu interview, 2–3; Fujimura, Though I Be Crushed , 64; Duncan Ryūken Williams, American Sutra: A Story of Faith and Freedom in the Second World War (Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2019), 127–28; Charles Oihe Hamasaki interview, Segment 21.

- ↑ Christgau, "Enemies" , 162–63; Vyzralek, "The Alien Internment Camp at Fort Lincoln," 10; Hitoshi "Hank" Naito interview, Segments 23 and 26; Arthur Ogami interview, Segment 28.

- ↑ Christgau, "Enemies" , 24–25, 35, 73, 92–134 passim.

- ↑ Christgau, "Enemies" , 92, 163, 166.

- ↑ "Site History, Fort Lincoln-United Tribes Site History," United Tribes Technical College website, accessed on July 20, 2020 https://archive.uttc.edu/fort-lincoln-united-tribes-site-history/site-history/ ; Barbara Wyatt, ed., Japanese Americans in World War II: National Historic Landmarks Theme Study (Washington, D.C.: National Historic Landmarks Program, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 2012), 164; Christgau, "Enemies" , 175.

- ↑ Hawaii Herald , Nov. 21, 2003, A–5; Ken Rogers, "Remembering 'Snow Country Prison,'" Bismarck Tribune , Sept. 19, 2003, accessed on Apr. 20, 2020 at https://bismarcktribune.com/news/local/remembering-snow-country-prison/article_f1b03e63-983e-5eee-a832-827dee02b88c.html ; "Snow Country Prison," North Dakota Museum of Art website, accessed on Apr. 20, 2020.

Last updated Jan. 9, 2024, 4:28 a.m..

Media

Media