Fort Missoula (detention facility)

| US Gov Name | Fort Missoula Internment Camp |

|---|---|

| Facility Type | Department of Justice Internment Camp |

| Administrative Agency | U.S. Department of Justice |

| Location | Missoula, Montana (46.8667 lat, -113.9833 lng) |

| Date Opened | December 18, 1941 |

| Date Closed | July 1, 1944 |

| Population Description | Held more than 1,000 Italian seamen captured in U.S. waters; also held 1,250 Japanese immigrants from the continental U.S. and Hawai'i. |

| General Description | Located at an old U.S. Army post on the southwest edge of Missoula, Montana, that was turned over to the Department of Justice (DOJ) in 1941. Missoula is in western Montana. |

| Peak Population | 2,003 |

| National Park Service Info | |

Army fort that became a Justice Department-run internment camp during World War II that held both stranded Italian seamen and Japanese internees. Over a thousand Issei male internees spent time at the Fort Missoula Alien Detention Center in two main groups. The first, consisting mostly of Issei leaders from the West Coast, began arriving shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor and were mostly transferred to other camps by the summer of 1942. A second group, which included Issei from Hawai'i and Japanese Latin Americans , began arriving in the spring of 1943, many remaining until the closing of the camp on July 1, 1944.

Background

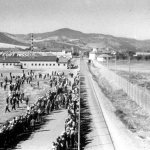

Fort Missoula, Montana, was established in 1877 as a late outpost in the ongoing warfare between American settlers and Native Americans. When the latter had been defeated, it became largely, in the words of its chronicler, Carol Van Valkenburg, "a fort without a purpose" and was sparsely manned by the army through much of the early 20th century. In the 1930s, it became a district office for the Civilian Conservation Corps. It was located in a picturesque dry lakebed four miles southwest of the town of Missoula, on the western edge of Montana. Surrounded by mountains, its climate was relatively mild compared to the rest of the state. [1]

Internees

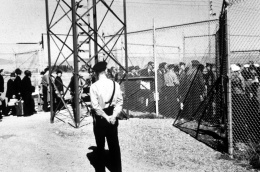

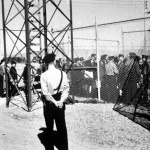

In March of 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered the seizure of 65 German, Italian, and Dutch ships that had been stranded in American controlled ports since the British declaration of war against Germany and Italy in September 1939. Needing a place to hold the Axis crews of the ships, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) acquired control of Missoula from the army in April 1941. Adding additional barracks as well as fencing and guard towers, Missoula became the main site holding crew members from Italian ships starting in May. Over the next several weeks, about 1,000 Italians arrived. About half came on one ship, the Conte Biancamano , a cruise ship that had been stranded in the Panama Canal Zone, while staff members of the Italian Pavilion of the 1939–40 New York World's Fair made up another sizable group. A small number of resident Italian and German internees detained for suspected pro-fascist ideology joined the mix leading to some conflict between pro- and anti-fascist internees. The camp superintendent was Nick Collaer. [2]

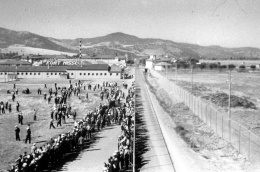

There were two distinct groups of Japanese American internees at Missoula. The first began to arrive shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Consisting mostly of Issei male community leaders from western states, the first group, from the Salt Lake City, Utah, area, arrived on December 18, and many more followed. There were 633 Japanese internees by the end of 1941 and total population of about 2,000 men in April 1942, roughly evenly split between Japanese and Italians. The average age of the Issei was around sixty. [3]

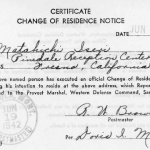

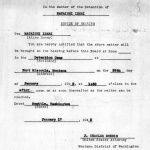

Starting in January 1942, Alien Enemy Hearing Boards from throughout the West began arriving at Missoula to administer hearings to Issei from their areas. A board from Seattle, for instance, would conduct hearings for Issei from Seattle. These boards, made up of prominent local citizens, heard the government cases against the men and also interrogated them about their prewar activities and views of Japan and the U.S. A local Montana board also heard some cases. One of the members of the Montana board was Mike Mansfield, then an instructor at the University of Montana, who would go on to a long career as a U.S. senator and American ambassador to Japan. After the hearings, the boards recommended that the internee be released, paroled, or interned for the duration. Over 70% were recommended for internment. These men were subsequently moved to U.S. Army run camps, in most cases either to Fort Sill, Oklahoma ; Camp Livingston, Louisiana or Lordsburg, New Mexico . "Parole" in practice for West Coast internees meant joining the mass forced exodus of Japanese Americans from the West Coast and eventually being assigned to another concentration camp. With the post-hearing releases and transfers, nearly all this first group of Issei had left Missoula by the end of 1942, with fewer than 30 remaining. [4]

In early 1943, the rising number of POWs began to strain the army's capacity to hold both the POWs and the internees. Thus, the army asked the Justice Department, which oversaw the INS camps, to take back the internees. The second group of Issei began to arrive at Missoula from army-administered camps starting in the spring of 1943, and there were 390 men by November 1943. Many of these men were from Hawai'i, while another group consisted of 130 Japanese Latin Americans. [5]

Life in Missoula

The Italian and Japanese groups were kept in separate fenced compounds, and interaction between the groups was minimal. Issei were housed in long, centrally heated wooden barracks that held thirty-eight men each. The men slept in cots that lined the walls. There were nearby bathroom facilities with flush toilets and hot and cold running water. The internees ate in mess halls. The Italians slept in two large stucco buildings. Both groups were allowed to form executive boards to represent their interests. [6]

Inmate accounts of life at Missoula paint a mixed picture, with allegations of mistreatment in its early weeks eventually leading to relatively serene conditions later, particularly during the second internment period in 1943–44. In his memoir, Rev. Yoshiaki Fukuda, a Konko-kyo minister from San Francisco who was part of the first group recalled that the internees—who were initially not made aware of their rights under the Geneva Convention—were forced to work outside of the camp in harsh winter weather for no pay. Fukuda and others also describe harsh treatment stemming from immigration investigators who held suspected illegal immigrants in solitary confinement, with allegations that the investigators and their Korean translators berated and physically assaulted them in their questioning. A subsequent INS investigation substantiated these charges, and as a result, three INS agents were suspended and two Korean interpreters fired. [7]

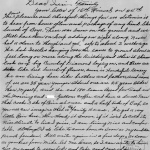

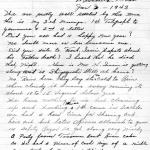

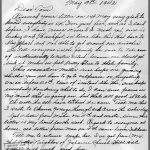

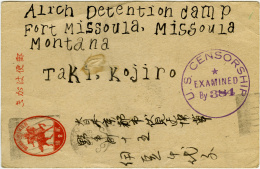

After this early period, accounts of life at Missoula paint a generally benign picture, with conditions there described as "very good" relative to other sites holding internees. [8] Issei fought boredom in various ways. As at other camps, writing and receiving letters was the only way to keep in touch with family and the outside world, though letters had to be written in English. Internees with English writing ability were called on to write letters for those without it. For younger men, sports became important. Issei built a nine-hole golf course dubbed the "Beautiful Sky Golf Course" and organized softball teams. There was even a game between the Japanese and Italians in July 1942. They were sometimes allowed to fish in the Bitterroot River and to shop in the town of Missoula. There were also movies, Christian and Buddhist religious services, and internee led classes. Because many of the Italian internees had been cruise ship employees, many had performance skills, and they put on shows for the other men. Many internees took to making craft objects, with the local specialty becoming objects made from pebbles. [9] Seattle internee Iwao Matsushita wrote, "So avid is this stone picking that it is said that anyone not involved in this hobby is not human." Matsushita, one of the few Issei who remained in the camp late in 1943 reported that security loosened over time and that the few Japanese left began to "mingle with the Italians at the movies or picnic down at the riverside." [10]

In her study of the internment of Issei from Hawai'i, Gail Okawa writes that in contrast to the treatment of Issei in the first group, "living conditions for the Hawai'i Issei"—who made up much of the second group—"seem to have been far less contentious." Hawai'i Issei internee Kumaji Furuya , who spent time in no less than seven different detention facilities, described Missoula as the "best of all the internment camps in which we had lived" and "an oasis during our dreary internment experience." Matsushita wrote in in a January 30, 1943 letter, "We've heard from people who left here for other camps, and they say there's no place like Missoula. The mail is on time, food is good, and the scenery is great." Both Collaer, who was reassigned to help establish the Crystal City Internment Camp in the summer of 1942, and his successor, Bert H. Fraser, seemed to be well regarded. [11]

Aftermath

Missoula closed on July 1, 1944. The remaining Issei were sent to another INS-run camp in Santa Fe, New Mexico . The camp returned to army control, where it became an army prison. After the war, the army, U.S. Forest Service, the University of Montana, and other institutions have used various buildings at the site. [12]

Today, the site is part of the Historical Museum at Fort Missoula and Rocky Mountain Museum of Military History. The inmate barracks were removed in the 1950s, with some being moved to the Montana State Fairgrounds. One is back at the site as part of the museum and contains an exhibition on the Alien Detention Center period. There are other period buildings still standing, the most significant of which is the post headquarters building, where the internee hearings were held. The courtroom used for the hearings has been restored and a restoration of full building is in progress as of 2021. [13]

For More Information

" Fort Missoula Alien Detention Center. " The Historical Museum at Fort Missoula website.

Fiset, Louis. Imprisoned Apart: The World War II Correspondence of an Issei Couple . Foreword by Roger Daniels. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997. [Letters between Iwao Matsushita at Fort Missoula, Montana, and Hanaye Matsushita at Minidoka.]

Flewelling, Stan. Shirakawa: Stories from a Pacific Northwest Japanese American Community. Foreword by Gordon Hirabayashi. Auburn, WA: White River Valley Museum, 2002.

Furuya, Suikei. An Internment Odyssey: Haisho Tenten . Translated by Tatsumi Hayashi. Foreword by Gary Y. Okihiro. Introduction by Brian Niiya and Sheila Chun. Honolulu: Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai'i, 2017.

Kashima, Tetsuden. Judgment Without Trial: Japanese American Imprisonment during World War II . Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002.

Okawa, Gail Y. Remembering Our Grandfather's Exile: U.S. Imprisonment of Hawai'i's Japanese in World War II . Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2020.

Van Valkenburg, Carol Bulger. An Alien Place: The Fort Missoula, Montana, Detention Camp 1941-1944 . Missoula, MT: Pictorial Histories Publishing Company, Inc., 1995, 2009.

Wyatt, Barbara, ed. Japanese Americans in World War II: A National Historic Landmarks Theme Study . Washington, DC: National Historic Landmarks Program, National Park Service, August 2012.

Footnotes

- ↑ Carol Van Valkenburg, An Alien Place: The Fort Missoula, Montana, Detention Camp 1941-1944 (Missoula, Mont.: Pictorial Histories Publishing Company, Inc., 1996, 2009), 2–7, quote from page 2; Louis Fiset, Imprisoned Apart: The World War II Correspondence of an Issei Couple (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997), 40.

- ↑ Van Valkenburg, An Alien Place , 5–37; Tetsuden Kashima, Judgment Without Trial: Japanese American Imprisonment during World War II (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002), 109.

- ↑ Van Valkenburg, An Alien Place , 51–54.

- ↑ Van Valkenburg, An Alien Place , 65–75; Stan Flewelling, Shirakawa: Stories from a Pacific Northwest Japanese American Community (Auburn, Wash.: White River Valley Museum, 2002), 189–99; Fiset, Imprisoned Apart , 50–51.

- ↑ Louis Fiset, Imprisoned Apart , 74; Van Valkenburg, An Alien Place , 97–105.

- ↑ Fiset, Imprisoned Apart , 40–41; Van Valkenburg, An Alien Place , 54, 58.

- ↑ Yoshiaki Fukuda, My Six Years of Internment: An Issei's Struggle for Justice , commentary by Stanford M. Lyman (San Francisco: Konko Church of San Francisco, 1990), 39–40; Van Valkenburg, An Alien Place , 77–85; Fiset, Imprisoned Apart , 45–46; Kashima, Judgment Without Trial , 184–86; Hyung-ju Ahn, Between Two Adversaries: Korean Interpreters at Japanese Alien Enemy Detention Centers during World War II (Fullerton: Oral History Program, California State University, Fullerton, 2002), 78.

- ↑ Fiset, Imprisoned Apart , 44.

- ↑ Jiro Oishi interview by Charles Kikuchi, July 7, 1943, pp. 15–16; Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study Collection, Bancroft Library, University of California at Berkeley, BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder T1.931, http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_b278t01_0931.pdf ; Van Valkenburg, An Alien Place , 55–58; Fiset, Imprisoned Apart , 53–56; Tom Matsuoka interview by Alice Ito, Segment 23, May 7, 1998, Ridgefield, Washington, Densho Visual History Collection, Densho Digital Repository, https://ddr.densho.org/media/ddr-densho-1000/ddr-densho-1000-47-transcript-a2ad72a07a.htm .

- ↑ Letter, Iwao Matsushita to Hanaye Matsushita, May 20, 1942, in Fiset, Imprisoned Apart , 146; letter, Iwao Matsushita to Hanaye Matsushita, Sept. 16, 1942, in Fiset, Imprisoned Apart , 175.

- ↑ Gail Y. Okawa, Remembering Our Grandfather's Exile: U.S. Imprisonment of Hawai'i's Japanese in World War II (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2020), 99; Suikei Furuya, An Internment Odyssey: Haisho Tenten , translated by Tatsumi Hayashi, foreword by Gary Y. Okihiro, introduction by Brian Niiya and Sheila Chun (Honolulu: Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai'i, 2017), 163, 165; Letter, Iwao Matsushita to Hanaye Matsushita, Jan. 30, 1943, in Fiset, Imprisoned Apart , 232. Herbert Nicholson , a Quaker missionary who was a well known supporter of Japanese Americans during World War II, came to Missoula to translate for Issei at their hearings. He praised Collaer for his respect for the internees and his opposition to their internment. (Van Valkenburg, An Alien Place , 70.) Van Valkenberg writes that Collaer's successor, Bert Fraser, "continued Collaer's enlightened policies." (Van Valkenburg, An Alien Place , 108.) In his memoir, Furuya called Fraser "a sensible man, who did an excellent job of managing our camp operations."

- ↑ Kashima, Judgment Without Trial , 109; Wallace J. Long, The Military History of Fort Missoula (Missoula, Mont.: Friends of Historical Museum at Fort Missoula, 1983, 1991, 2005) 16–17, accessed on May 29, 2014 at https://fortmissoulamuseum.org/history/ .

- ↑ Van Valkenburg, An Alien Place , 112–13; Barbara Wyatt, ed., Japanese Americans in World War II: A National Historic Landmarks Theme Study (Washington, D.C.: National Historic Landmarks Program, National Park Service, August 2012), 165; "Fort Missoula Alien Detention Center," The Historical Museum at Fort Missoula website, accessed on June 13, 2021 at https://fortmissoulamuseum.org/exhibit/fort-missoula-alien-detention-center/ .

Last updated Jan. 9, 2024, 4:39 a.m..

Media

Media