GI Bill

To address potential problems as a result of an unprecedented number of demobilized veterans following the conclusion of World War II, Congress passed the Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944 or the GI Bill. In addition to funding important projects like the construction of hospitals for veterans, unemployment compensation, and low interest farm, home, and business loans, it also paid for veterans to attend college. For Japanese Americans veterans, the GI Bill would enable unparalleled educational and economic opportunities in the 1950s that would result in their political, economic, and social ascendancy. [1]

History and Impact of the GI Bill

Following World War I, many veterans were given only a train ticket to return home and a $60 stipend. However, following the Great Depression, Congress implemented the World War Adjusted Act of 1924 or the Bonus Act to address some of the economic problems facing veterans. Although veterans were promised a bonus based on the numbers of days served, many would not be paid for twenty years. Subsequently, in June 1932 nearly 15,000 to 20,000 veterans marched on Washington D.C. to request early payment of bonuses due to them in 1945. They dispersed only after U.S. troops used tear gas and bayonets. To prevent a recurrence of the Bonus March, veterans' organizations and members of Congress began lobbying for benefits for returning World War II veterans. After great debate, in 1944 Congress approved the Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944 or the GI Bill. The GI Bill appropriated $500 million to build veterans' facilities including hospitals. It also approved unemployment benefits of $20 per week for one year with the U.S. Employment Service providing job placement services. The GI Bill also paid for four years of education and training and a monthly stipend of $50 was given to single veterans while those with dependents were allocated $75. Additionally, it guaranteed 50 percent of business, home, and farm loans up to $2,000 at an interest rate no greater than 4 percent. [2]

Between August 1945 and December 31, 5.4 million soldiers and sailors were demobilized, double original estimates. Many began to immediately utilize their GI Bill benefits. Most drew unemployment benefits for fewer than twenty weeks, and only 14 percent of them exhausted their maximum entitlement of one year. Over the next few years, 29 percent received government-backed loan guarantees that allowed some 4 million veterans to buy homes at low interest rates. The GI Bill also enabled 200,000 veterans to purchase businesses and farms. However, the greatest success of the GI Bill was reflected in the educational opportunities as nearly 51 percent of veterans benefited from the education provision and almost 2.2 million attended a four year university or college. Over 5.6 million more pursued training in certificate or short course programs. [3] According to one scholar, the GI Bill was, "without question, one of the largest and most comprehensive government initiatives ever enacted in the United States . . . And in the process of changing so many individual lives, it helped alter the institutional and physical landscape of postwar America." [4] Even more than the Pell Grant, the GI Bill created economic opportunities for large populations of various groups in America.

Many of these changes were the result of unprecedented access to higher education that also enabled veterans to stay in school. According to one estimate, these former soldiers gained 2.7-2.9 years of education that allowed 350,000 to enroll in professional and graduate degree programs. Subsequently, veterans were able to obtain better jobs, higher incomes, better benefits, and increased status and social mobility. For minorities like Japanese Americans, the GI Bill enabled unprecedented economic and social progress within a single generation.

GI Bill and Japanese Americans

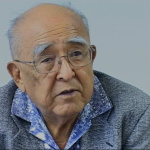

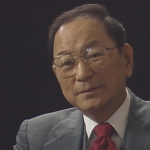

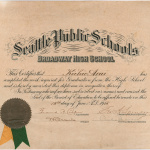

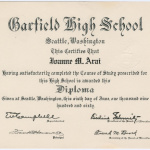

Following their experiences in war, many Nisei veterans returned to their communities with a new perspective and desire for change. By fighting and dying on behalf of the United States to prove their loyalty, Japanese American soldiers believed they had earned their rightful place as equals within society. Through the GI Bill, many became the first in their families to attend college, with some even attending medical and law schools. Thus, in the postwar period, many Nisei entered professional occupations and became teachers, doctors, and lawyers, while in Hawai'i, others took advantage of the tourism boom in the 1950s to enjoy unprecedented profits from businesses catering to the burgeoning tourist industry. This desire for political, social, and economic change also led many veterans in Hawai'i to support the Democratic Party and align themselves with other prominent Nisei who had emerged as leaders within the Japanese community during World War II. Thus the economic and professional gains that many Nisei had achieved in the postwar period as a result of the GI Bill became mirrored in their political ascendancy in the Revolution of 1954 as former soldiers like Spark Matsunaga and Daniel Inouye became United States Senators while MIS veteran George Ariyoshi became the first governor of Japanese ancestry. [5]

For many Nisei veterans and their families as well as the larger Japanese community, the GI Bill had a profound impact as it resulted in a fundamental shift in the status of Japanese Americans both in Hawai'i and the mainland. For the first time, large numbers of Japanese Americans were able to envision a future beyond the plantations and produce markets and attain middle-class status as professionals, business owners and homeowners. With the aid of the GI bill, many veterans were able to break down housing restrictions that had previously characterized the prewar period. The GI bill also helped to accelerate generational and leadership changes in the Japanese American community. As a result of the absence of traditional Issei leaders who had been interned, and because of the war-spawned role reversal of traditional Japanese social patterns, prominent Nisei assumed the leadership roles within the Japanese community. While World War II did create great upheaval within the Japanese American community, veterans were able to take advantage of the changes of the period to reshape the future of the ethnic community.

For More Information

Altschuler, Glenn C. and Stuart M. Blumin. The GI Bill: A New Deal for Veterans . New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Brooks, Charlotte. Alien Neighbors, Foreign Friends: Asian Americans, Housing, and the Transformation of Urban California . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

Hazama, Dorothy Ochiai and Jane Okamoto Komeiji. Okage Sama De: The Japanese in Hawaii 1885-1985 . Honolulu: Bess Press, 1986.

Kurashige, Scott. The Shifting Grounds of Race: Black and Japanese Americans in the Making of Multiethnic Los Angeles . Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008.

Robinson, Greg. After Camp: Portraits in Midcentury Japanese American Life and Politics . Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012.

Footnotes

- ↑ Research for this article was supported by a grant from the Hawai‘i Council for the Humanities .

- ↑ Glenn C. Altschuler and Stuart M. Blumin, The GI Bill: A New Deal for Veterans (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 71.

- ↑ Altschuler and Blumin, The GI Bill , 83.

- ↑ Altschuler and Blumin, The GI Bill , 83.

- ↑ For more information on the postwar rise of the Nisei, consult Dorothy Ochiai Hazama and Jane Okamoto Komeiji, Okage Sama De: The Japanese in Hawaii 1885-1985 (Honolulu: Bess Press, 1986), 177-218.

Last updated Jan. 18, 2024, 4:15 p.m..