George Nakashima

| Name | George Nakashima |

|---|---|

| Born | May 24 1905 |

| Died | June 15 1990 |

| Birth Location | Spokane, Washington |

| Generational Identifier |

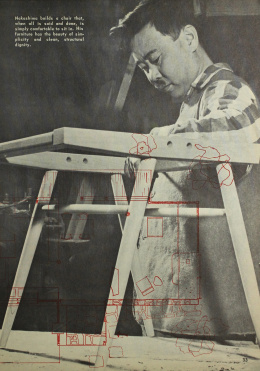

George Nakashima (1905–90) was a world-famous woodworker in the second half of the twentieth century. He achieved fame as a leader of the modern American Arts and Crafts movement against a backdrop of increasing skepticism on accelerated mechanization, mass production, and the rationalization of life and work. He attained a distinctive place in the world of American arts and crafts with his original furniture, which was often described by his admirers and art critics as merging the Shaker tradition and Eastern influence into the organic whole. In establishing his own style, his days at Minidoka during World War II played an important role along with his travels to France, India, and Japan. Although it was a traumatic and humiliating experience, his time in the camp provided him with an opportunity to work closely with a well-trained Japanese carpenter, which had a significant impact on the rest of his career as a Japanese American woodworker.

Trained in Architecture

George Nakashima was born in Spokane, Washington, in 1905. His father, Katsuharu Nakashima, had immigrated to America from Tottori, Japan. As a journalist for the Japanese-language newspaper Taihoku Nippō , Katsuharu was a well-known figure in the Northwest Japanese American community. George's mother, Suzu Toma, had served as an attendant in the Meiji Imperial Court before leaving for America as a picture bride . Encouraged by his parents' emphasis on education, Nakashima enrolled at the University of Washington and studied forestry and architecture. An outstanding architecture student, Nakashima received a one-year scholarship to study at the École Américaine de Beaux-Arts in Paris. After graduating from the University of Washington, he enrolled briefly in the Harvard Graduate School of Design in 1929 and then transferred to Massachusetts Institute of Technology where he earned a master's degree in architecture in 1930. Upon completing his academic work, he acquired a job as an architectural designer for the Long Island State Park Commission until the Great Depression terminated his work, which set him off on a world journey in search of experiences that would stimulate his young mind.

His first stop was Paris. Returning to the city after several years gave him a firsthand look at the latest works of Le Corbusier, whom he admired greatly. Despite the architectural and artistic tradition and vigor he perceived in the city, he recounted that he "could not help feeling that Paris lived in the past in spite of the powerful inspiration of modern art and architecture" and decided that he should move on. [1]

The next destination was his ancestral land, Japan. In 1934, Nakashima was introduced to Antonin Raymond, who had worked with Frank Lloyd Wright at his Taliesin workshop in 1916 and was in Japan to help him with the Imperial Hotel project in Tokyo. Working as a member of the Raymond office, Nakashima fostered friendships with Japanese colleagues such as Junzo Yoshimura and Kunio Maekawa, who were to lead the postwar Japanese architectural world. Living in a Japanese house and visiting historic sites in Kyoto and Nara, he familiarized himself with the traditional Japanese architecture and way of life, along with the teachings of Buddhism and Shintoism, through which he learned how the Japanese respected and coexisted with nature in their longstanding history. During his stay in Japan, Nakashima designed St. Paul's Catholic Church and interiors at Karuizawa that were commissioned to Raymond's office.

As a representative of the Raymond office, Nakashima went to Pondicherry, India, in 1936 to supervise the construction of the dormitory and design and direct the production of the building's furniture for the spiritual community organized by Sri Aurobindo. Nakashima became absorbed in Sri Aurobindo's teachings, which was based on karma yoga, the discipline of letting go of egotism as a way of seeking divine union, and lived as a community member, cut off from materialism that prevailed on the outside world. Nakashima refused a salary for his work because he was grateful for receiving the answer to his search for the meaning of life. Although he eventually went back to Japan, he remained a firm believer in Sri Aurobindo's teachings which made him skeptical of mass production, egotism, and a society of isolated individuals.

When Nakashima returned to Japan in 1939, he worked with Kunio Maekawa on an architectural project for six months and met his future wife Marion Okajima, a Japanese American who was working as a private English tutor in Tokyo at the time. The couple married in Los Angeles in 1941. Eager to study America's architectural progress after spending many years abroad, Nakashima took a survey of Frank Lloyd Wright's latest buildings in California. He was disappointed with the inadequate workmanship that the structural aspects of the architecture reflected and how the design and construction processes were separated from each other. He was convinced that he should leave architecture so that he could be in charge of his production from beginning to end. Thus, his passion turned to woodworking, which he had been practicing since his time in Japan. George and Marion began their married life in Seattle in 1941, when they met Maryknoll Father Leopold H. Tibesar, a Japanese-speaking Catholic priest active in the Seattle Japanese American community. Tibesar allowed Nakashima to use the basement of the Maryknoll regional house in Seattle as his workshop in exchange for teaching woodworking to local boys.

Incarceration Experience

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the incarceration of all West Coast residents of Japanese ancestry brought Nakashima's new life and endeavors to a halt. Nakashima, his wife, and their newborn daughter were removed to the Minidoka War Relocation Authority camp in Hunt, Idaho.

Because he had skills as an architect, he was assigned to design and plan rooms and housing for the social betterment of the camp. Nakashima utilized scrap lumber left over from building the barracks and additional materials that he collected out in the desert to make a model apartment. He tried to give his and fellow Japanese Americans' incarcerated lives some level of comfort and dignity. He was paid $19 per month and continued that job until he left the camp in May 1943.

One of the camp residents was an experienced Issei carpenter, Gentaro Kenneth Hikogawa , who collaborated with Nakashima on his job building rooms for display. Through their collaborative work, the carpenter trained Nakashima to refine skills as a woodworker. Hikogawa taught Nakashima how to use and take care of Japanese hand tools that were to become essential in Nakashima's postwar production. In later years, Nakashima's knowledge of Japanese wood joinery, which he owed to Hikogawa, surprised Japanese artisans who assumed that no Americans would know about it. Although the incarceration restricted the freedom of the up-and-coming woodworker, it could not contain his passion for work and knowledge.

Looking back, Nakashima expressed his bitter feeling about the incarceration in his autobiography: "[The incarceration] I felt at the time was a stupid, insensitive act, one by which my country could only hurt itself. It was a policy of unthinking racism." [2] The days that he spent in the desert of Idaho were harsh, yet the intimate environment of the camp provided Nakashima with an opportunity to reconnect with the Japanese American community.

Post-Incarceration Life and Career

Thanks to the efforts of Antonin Raymond, his wife, and other supporters who petitioned for Nakashima's release, he and his family were able to leave the camp in May 1943. As the sponsor of the released family, Raymond invited Nakashima to work on his farm in New Hope, Pennsylvania. After working for his former boss for about a year and saving up some money, Nakashima bought a piece of land and built his workshop—all from scratch—where he could devote himself to woodworking. The popularity of his furniture gradually increased among the wealthy in Bucks County, which was known for its small but traditional artistic community, and eventually in larger cities from coast to coast.

From 1946 to 1954 and 1957 to 1961 respectively, Nakashima designed lines for Knoll Studios and Widdicomb-Mueller, internationally known designer furniture makers, which helped publicize his work to a broader audience. Although he worked with these major companies, he maintained his philosophy of supervising the entire production process at his workshop and maintaining full control of his business.

While he was firmly established as a woodworker by this time, he was also commissioned to design churches within and beyond the United States. When a group of Japanese American Catholics came up with a plan to build a church in Japan, Nakashima volunteered to design it. The Christ the King Church in Katsura, Kyoto, was dedicated to ten Maryknoll Fathers, including Nakashima's acquaintance Leopold H. Tibesar, who had opposed the Japanese American incarceration and followed detainees into the camps to serve as chaplains and provide emotional support to them. Not far from the Katsura Palace, to which Nakashima often referred as the epitome of Japanese traditional design and aesthetics, the church remains one of the historically important modern buildings in Japan.

Nakashima's ties to Japan were reinforced when internationally known sculptor Masayuki Nagare invited him to join Sanuki Minguren, an association of designer-craftsmen based in Kagawa, Japan, in 1964. As a woodworker who questioned mass production and believed in producing unique furniture with the hands of craftsmen, Nakashima readily supported Minguren. Nakashima collaborated with local artisans to invent various new ways to utilize traditional craftsmanship in the modern context. His spirit has been widely recognized through the workshop in Kagawa that operates under Nakashima's license—the only one outside New Hope today.

Toward the end of his career, Nakashima dedicated himself to the Peace Altar Project, campaigning for peace through presenting his beautifully handcrafted altars to various groups in the United States and abroad. Experiencing various cultures firsthand and identifying himself as Hindu, Indian, Catholic, Japanese, American, Nisei, and a world citizen, he firmly believed that a culture starts from small beginnings and that American culture could not be forced upon others. He continued to question the materialism and consumerism that he believed had come to characterize mainstream American culture. The numerous honors that he received throughout his career include the Gold Craftsmanship Medal from the American Institute of Architects (1952), the Gold Medal and Title of "Japanese American of the Biennium in the Field of the Arts" from the Japanese American Citizens League (1980), and the Third Order of the Sacred Treasure from the Japanese government (1983).

For More Information

"George Nakashima Papers." The James Michener Museum, Doylestown, Pennsylvania.

George Nakashima Woodworker. http://www.nakashimawoodworker.com/ .

Nakashima, George. The Soul of a Tree . Tokyo: Kodansha International Ltd., 1981.

Nakashima, Mira. Nature, Form, and Spirit: The Life and Legacy of George Nakashima . New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2003.

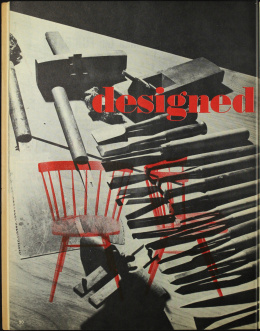

Shimano, Eddie. "Designed for Living: George Nakashima Handcrafts a House in Pennsylvania." Scene the Pictorial Magazine Vol. 2, No. 1 (May 1950): 30-1, 34. http://ddr.densho.org/ddr/densho/266/18/mezzanine/ff308952a2/ .

Tajiri, Larry. "Modern Furniture Designer." Pacific Citizen , July 16, 1954, 7-8. http://ddr.densho.org/ddr-pc-26-29/

Last updated July 20, 2023, 4:46 p.m..

Media

Media