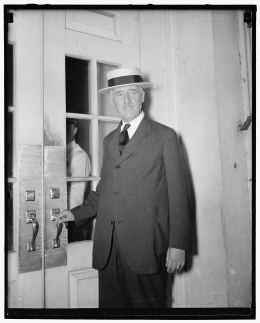

Henry Stimson

| Name | Henry Stimson |

|---|---|

| Born | September 21 1867 |

| Died | October 1 1950 |

| Birth Location | NY |

Wartime secretary of war. One of the most influential and durable American statesmen of the 20th century, Henry Stimson (1867–1950) served on the cabinets of three different presidents and set much of the template for the American foreign policy establishment. As secretary of war during World War II, he ultimately approved mass removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans as recommended by his military advisors.

To World War II

By the time he was appointed secretary of war by Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1940, Henry Stimson was seventy-three years old and was regarded as an elder statesman with a formidable foreign policy resume. He was born on September 21, 1867, to a wealthy family in New York and attended the elite prep school Phillips Andover before graduating from Yale University and Harvard Law School. His mother died when he was eight, and Henry and his sister were largely raised by grandparents and an aunt, his father being largely absent from his early life.

Upon his graduation from law school, he joined the prestigious Wall Street firm Root and Clark in 1891, where he made partner in two years. Founder Elihu Root, a future secretary of war and secretary of state, became his mentor. In 1893, he married Mabel Wellington White, to whom he remained married until his death. The couple had no children.

In 1906, President Theodore Roosevelt appointed him to a post as U.S. attorney in New York, where he made a name for himself prosecuting anti-trust cases. He used this position as a springboard to a political career, running for governor of New York in 1910 as a Republican, losing to Democrat John Alden Dix. In 1911, President William Howard Taft appointed him secretary of war, a position he held for two years. He subsequently served in World War I in France as an artillery officer, attaining the rank of colonel in 1918. He served as governor-general of the Philippines from 1927 to 1929, then was appointed secretary of state in 1929 by President Herbert Hoover, serving for the duration of Hoover's term. After Japan's invasion of Manchuria in 1931, he issued the Stimson Doctrine, whereby the U.S. would refuse to recognize territorial changes that were executed by force.

As war clouds hung on the horizon in the late 1930s, President Roosevelt began to build a bipartisan cabinet to gird for the coming war. He reached out to the lifelong Republican and internationalist Stimson, who agreed to join the cabinet for his second stint as secretary of war and was appointed in July 1940, alongside fellow Republican Frank Knox , appointed as secretary of the navy.

The War Years

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Stimson soon found himself presiding over a dispute between the Justice and War Departments over the fate of Japanese Americans on the West Coast. The Justice Department was led by Attorney General Francis Biddle , whose top aides James Rowe and Edward Ennis were adamantly opposed to mass removal of Japanese Americans. Stimson presided over military leaders who just as adamantly favored mass removal as "military necessity." Though Stimson was initially against mass removal of the Japanese—and though he understood the constitutional difficulties such action would create—he ultimately chose to believe military advisors pressing for removal under the rationale of military necessity.

After a brief initial period of calm, pressures began to mount to take harsh action against Japanese Americans in January and February of 1942. On January 16, California Congressman Leland Ford wrote to Stimson and Biddle calling for the incarceration of all Japanese Americans in "inland concentration camps." Deflecting the demand to Biddle for the time being, he forwarded a plan from Western Defense Command head General John L. DeWitt calling for the removal of 7,000 aliens (3,000 Japanese) to Biddle on January 24, which Biddle agreed to. On February 3, he met with Allen Gullion , the provost marshal general of the U.S. Army and one of the most ardent backers of mass exclusion. Gullion pushed for mass removal by presenting "evidence" of Japanese American communication with Japanese submarines. (No such communication was ever documented.) Unconvinced, Stimson opposed any mass exclusion at this point. But he would have a change of heart.

Continued pressure from both West Coast politicians and military advisors such as Gullion and Karl Bendetsen —and eventually from his protege and chief deputy John McCloy —eventually wore down his resistance. Along with John McCloy, Stimson requested a meeting with the President Franklin Roosevelt to decide the issue. Unable to secure a meeting, the pair spoke on the phone to the President on the afternoon of February 11, at which time the President expressed his support for whatever course Stimson choose. After the call, McCloy called Bendetsen to give him the go-ahead to start formulating a plan for mass removal. On February 17, the President gave final approval to Stimson and McCloy, at which point Biddle ended his opposition, due in large part, he later claimed, to the high esteem in which he held Stimson. A final meeting at Biddle's house that evening sealed the deal.

Why had Stimson come to support mass removal of Japanese Americans despite understanding the constitutional issues? In his autobiography, he cites the probability of "Japanese raids on the west coast" and that "it was quite impossible to be sure that the raiders would not receive important help from individuals of Japanese origin." [1] His diary entry of February 27 also provides a clue:

The second generation Japanese can only be evacuated either as part of a total evacuation, giving access to the areas only be permits, or by frankly trying to put them out on the ground that their racial characteristics are such that we cannot understand or trust even the citizen Japanese. The latter is the fact but I am afraid it will make a tremendous hole in our constitutional system. [2]

Both of these passages suggests a belief in the same racial stereotypes that men like DeWitt have been vilified for. His biographer, Godfrey Hodgson, also suggests that his agreement to mass removal was "of a piece with his overall strategic perception" and that he was "unapologetic about the use of force in what he considered to be a good cause." [3]

Over the next few months, Stimson was involved in the debate about Japanese Americans in Hawai'i, favoring some sort of large scale exclusion plan of enemy aliens. However he and other administration officials were ultimately stonewalled by Hawai'i military commander Delos Emmons , and only a limited incarceration of Japanese in Hawai'i took place. In 1943, at the urging of McCloy, he supported the cause of allowing Nisei in the army both for its propaganda value and for the role it could have in integrating Japanese Americans back into American society after the war. Stimson agreed to end exclusion from the West Coast in May of 1944, but also agreed to delay allowing Japanese Americans to return there until after the November 1944 elections.

Aside from his role in Japanese American incarceration, the other decision that is often cited as a blot on his record also involved "Japanese": his shepherding of the Manhattan Project and his strong advocacy of using the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, decision that has only become more controversial as the years have passed.

Final Years

In failing health, and losing influence in the cabinet, Stimson stepped down on September 21, 1945. In his last years he focused on his legacy, writing his memoirs with the assistance of McGeorge Bundy, taking part in a pioneering oral history project at Columbia University, and arranging for his diaries to be archived at the Yale University Library. He died at age 83 in October 1950 at his home in Huntington, New York. He has a middle school, a building at State University of New York at Stony Brook, and a think tank named after him.

For More Information

Daniels, Roger. Concentration Camps, North America: Japanese in the United States and Canada during World War II . Malabar, FL: Robert E. Krieger Publishing Co., 1981.

Hodgson, Godfrey. The Colonel: The Life and Wars of Henry Stimson, 1867–1950 . New York: Knopf, 1990.

"Introduction: The Diaries of Henry Lewis Stimson in the Yale University Library." Yale University Library. New Haven, CT.

Irons, Peter. Justice at War: The Story of the Japanese American Internment Cases . New York: Oxford University Press, 1983.

"Reminiscences of Henry Lewis Stimson: Oral History, 1949." Columbia Center for Oral Histories. Columbia University Libraries. New York. http://oralhistoryportal.cul.columbia.edu/document.php?id=ldpd_4075758 .

Robinson, Greg. By Order of the President: FDR and the Internment of Japanese Americans . Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001.

Stimson, Henry L., and McGeorge Bundy. On Active Service in Peace and War . New York: Harper & Brothers, 1948.

Henry L. Stimson Center. http://www.stimson.org/ .

Last updated Jan. 15, 2024, 4:46 a.m..

Media

Media