Immigration

Japanese immigrants to the United States were a diverse group of men and women with multiple, often conflicting motives and intents. Ranging from laborers looking to "get rich quick" to young students eager to further their education to political exiles fleeing from the Japanese government's restrictive laws, the Japanese who left their country for wide-ranging opportunities in a new land reflected the diversity and complexity of the country they left behind, and forged new networks and communities in the United States.

Japanese Origins

Immigration from Japan to the Territory of Hawai'i and the continental United States, particularly from the 1880s to 1924, occurred within a complex and rapidly shifting international context. Following over 250 years of self-imposed isolation, Japan was forced into diplomatic and trade relations by the United States in the 1850s. A period of internal conflict ensued, culminating in the 1868 overthrow of the Tokugawa shogunate, the military dynasty that had served as the de facto rulers of Japan since the seventeenth century. The new government, with the young Meiji emperor as its titular head, initiated a series of sweeping and broad-ranging changes to transform Japan into a modern nation-state in the hopes that Japan would avoid both informal and formal colonization by western powers at the height of imperialistic competition, and might eventually be accepted as an equal in a new global power struggle. These drastic changes, in turn, created the circumstances that both enabled and encouraged many, particularly rural, Japanese, to seek opportunities away from their ancestral villages, including immigrating to Hawai'i and the United States.

Japan's sudden and forced opening had a drastic effect on the national economy. While certain Japanese products such as tea and silk found an immediate and lucrative market abroad, the rapid changes and social upheaval and resulting dislocation of many rural residents left the Japanese countryside in disarray. Especially after an effort by the central government in the early 1880s to stem inflation through tax reform left many farmers destitute, rural youth began seeking work away from their ancestral villages. Many flocked to the urban centers of Tokyo and Osaka, but others chose to seek their fortunes abroad, in the Territory of Hawai'i and the continental U.S. In addition to economic opportunities, these young Japanese were also often attracted to the excitement, adventure, and intellectual and cultural stimulation that far-flung locations—until recently closed off to them—seemed to offer.

Simultaneous to the changes occurring in Japan, the United States was also undergoing changes that made the American West an ideal place to which Japanese might immigrate. American expansion across the continent to the West Coast, and America's entrance into the frenetic competition for new colonial territories in the Pacific, not only brought Japan into the American sphere of influence and interest, but also opened up the American West to migrants from the eastern and central U.S. and immigrants from both Europe and Asia.

Waves of Migration

Until the 1880s, with a few exceptions, emigration from Japan to the U.S. was quite limited. The very first group of immigrants, known as the "gannenmono" because they left in the first year—or gannen —of the Meiji period, were contract laborers recruited to work on Hawaiian sugar plantations through a joint effort by officials from the Kingdom of Hawaii and the new Japanese government. In the continental U.S., many of the early immigrants were well-educated students or entrepreneurs who flocked to urban centers along the West Coast in search of further educational and economic opportunities, and those who eventually settled often became the core of the economic and intellectual elite of the immigrant communities that developed along the West Coast.

Large-scale laborer immigration, to both Hawai'i and the continental U.S., did not begin in earnest until the mid-1880s, and continued until 1907, when the Gentlemen's Agreement between the U.S. and Japanese governments restricted further laborer immigration. Between 1895 and 1908, approximately 130,000 Japanese immigrated to Hawai'i and the U.S. [1] Unlike the first wave of immigrants who left Japan to seek an education as part of a wider effort to improve Japan's position in the world, the immigrants who began arriving in the 1880s left their homes mostly in search of quick economic opportunities, and initially, intended to return to Japan once they had earned enough money. Once news of a former village resident's successes abroad reached his or her village, others from the same village often followed suit, resulting in a concentration of immigrants from certain regions. Typical immigrants came from farming families with some resources, and were second or third sons who could not inherit their ancestral land. The practice of dekasegi , or migrant labor, had a long tradition in rural areas as a way to offset bad harvests or to supplement a family's income. Thus, initially, immigration to the Territory of Hawai'i and the continental U.S. was viewed as a form of dekasegi labor, and as an alternative to finding work in Tokyo and other urban centers or, after the turn of the twentieth century, in one of Japan's new colonies or territories.

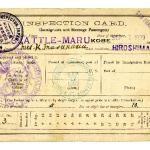

Until Hawai'i was annexed by the U.S. in 1898, most immigrant laborers to Hawai'i arrived under a labor contract that obligated them to work on a sugar plantation until their contracts expired. They were actively recruited by brokers in Japan that focused on residents in the southwestern prefectures such as Fukuoka, Hiroshima, Kumamoto, and Yamaguchi. Since laborers were paid much better in the continental U.S., some immigrants to Hawai'i moved on to the American West Coast at the end of their contracts instead of returning to Japan. When Hawai'i was annexed all existing contracts were voided, leading to a large-scale migration of Japanese laborers from Hawai'i to the West Coast in search of more lucrative economic opportunities.

In the burgeoning cities along the West Coast like San Francisco, Los Angeles, Seattle, and Portland, some of the earlier immigrants became professional labor contractors and actively recruited immigrants to work primarily in agriculture, but also in logging, mining, and the other local industries in need of manual labor. Japanese filled the void created when Chinese labor immigration was barred by the passage of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Law . Immigrants settled not only in coastal areas, but also in cities in the Intermountain West such as Salt Lake City and Denver, and in inland agricultural areas from the West Coast to the Rocky Mountains. While far fewer, and usually limited to students and entrepreneurs, Japanese also settled in other major American cities such as Chicago and New York.

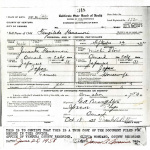

Following the Gentlemen's Agreement labor immigration was theoretically eliminated. However, since relatives of immigrants were still granted visas, a small number of family members and so-called " picture brides "—women who had agreed to marry male immigrants they had "met" only through the exchange of photographs and whose marriages had been arranged through intermediaries—continued to arrive in the U.S. until 1924, when all Japanese immigration was excluded.

Following the 1924 Immigration Act , Japanese continued to seek new opportunities abroad, but since they were no longer able to go to the U.S.—and as the Japanese Empire continued to expand—they immigrated instead to countries in Central and South America as well as areas under Japanese control or influence such as Korea, Taiwan, southern Sakhalin, islands in the South Pacific, treaty port cities in China, and Manchuria. After the end of World War II, Japanese women who married American soldiers stationed in Occupied Japan were granted special visas so that they could move to the U.S. It was not, however, until the passage of the McCarran-Walter Act in 1952 that Japanese immigration to the U.S. was legalized again.

For More Information

Azuma, Eiichiro. Between Two Empires: Race, History, and Transnationalism in Japanese America . New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Gordon, Andrew. A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present . New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Hane, Mikiso. Peasants, Rebels, and Outcasts: The Underside of Modern Japan . New York: Pantheon Books, 1982.

Ichioka, Yuji. The Issei: The World of the First Generation Japanese Immigrants , 1885-1924. New York: Free Press, 1988.

Kimura, Yukiko. Issei: Japanese Immigrants in Hawaii . Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1988.

Lee, Shelley Sang-Hee. Claiming the Oriental Gateway: Prewar Seattle and Japanese America . Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2010.

Moriyama, Alan. Imingaisha: Japanese Emigration Companies and Hawaii , 1894-1908. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1985.

Odo, Franklin, and Kazuko Sinoto. A Pictorial History of the Japanese in Hawaii , 1885-1924. Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press, 1985.

Footnotes

- ↑ Eiichiro Azuma, Between Two Empires: Race, History, and Transnationalism in Japanese America . (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 29.

Last updated June 22, 2020, 6:51 p.m..

![Certificate of residence [in Japanese] Certificate of residence [in Japanese]](https://encyclopedia.densho.org/front/media/cache/58/53/58534703c76c724035b2269a20119e0f.jpg)