Japanese American Joint Board

A panel of representatives from various federal agencies that made judgments about the loyalty or disloyalty of nearly 40,000 Japanese Americans between January 1943 and May 1944.

Background and Purpose

The Japanese American Joint Board (JAJB) came into existence as a result of the decision of the U.S. Army to recruit soldiers for a segregated combat team from within the camps administered by the War Relocation Authority (WRA) and the nearly simultaneous decision of the WRA to encourage Japanese Americans in the camps to leave for jobs in the country's interior. In order to bring these plans to life, both the army and the WRA found it essential to be able to certify to the public that Japanese Americans being released from the camps posed no security risk. The Army Provost Marshall General's Office had a similar concern; it was responsible for industrial security in industries doing work important to the war effort, and needed to be able to screen Japanese American applicants for employment in those industries.

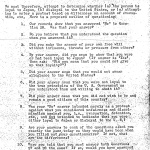

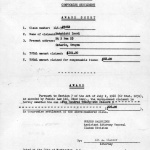

To facilitate these goals, the government required all prisoners in the WRA camps above the age of seventeen to fill out a questionnaire surveying certain aspects of their national, educational, financial, religious, and cultural backgrounds. The questionnaire also asked the prisoners about their willingness to serve in the military and to swear loyalty to the United States and forswear loyalty to the Emperor of Japan or any other foreign power. Along with intelligence information on the incarcerated Japanese Americans in the hands of several civilian and military agencies, these questionnaires created an enormous set of data on the incarcerated Japanese American community.

The JAJB was the board constituted to process this data and produce from it intelligible findings on the loyalty or disloyalty of individual Japanese Americans seeking to leave one of the camps, join the military, or work in an industry doing sensitive war work. The board was chaired by a representative from the office of Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy and initially had a voting representative from the Office of Naval Intelligence , the Office of the Assistant Chief of Staff of the Army's G-2 (Intelligence) Division, the Provost Marshall General's Office (PMGO), the War Department General Staff, the WRA, and the FBI. Just two months into the JAJB's work, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover withdrew his representative, leaving the WRA as the only civilian agency with a seat at the table.

At the beginning, the JAJB had two tasks: to make recommendations to the WRA about which Japanese Americans would be permitted to leave the WRA's camps and to state whether it objected to the employment of individual Japanese Americans in plants and facilities important to the war effort. Its main challenge was to devise a way of converting the vast amounts of information on the loyalty questionnaires and in the files of various intelligence agencies into data that would permit the processing of thousands of individual cases in a very short period of time. Assisting the JAJB in this effort was Calvert Dedrick, the chief of the Census Bureau's Statistical Research Division, whose services the Census Bureau loaned to the Office of the Assistant Secretary of War.

Decisions and Outcomes

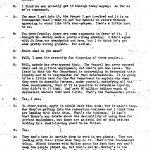

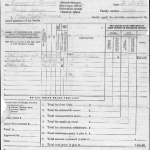

Dedrick's first proposal was a system that assigned positive and negative point values to a wide array of features of an individual Japanese American's background as revealed in his or her answers on the loyalty questionnaire. This system overtly and simplistically penalized stereotypically Japanese cultural attributes and rewarded stereotypically American ones: for example, a Japanese American received negative points for being a Buddhist and positive points for being a Christian, negative points for being an instructor of "Japanese hobbies or sports" and positive points for being an instructor in "an American sport of hobby." After a month, however, Dedrick reported that this system was unworkable. He replaced it with a system that looked for certain recurring patterns of innocent or suspicious attributes and affiliations—again determined along the simplest of racial and cultural lines—and used those patterns to place Japanese Americans into a "white" group who could be approved without further inquiry, a "black" group who could be denied without further inquiry, and a "brown" group in the middle whose files required individualized review and consideration.

Using this system, the JAJB adjudicated the cases of 38,449 Nisei in fifteen months and made adverse findings in 12,404 of them—nearly one-third.

The impact of these adverse findings was less detrimental to Japanese Americans than the numbers would suggest because the JAJB lost influence due to internal conflict. The WRA saw the JAJB as dominated by military agencies that had no experience with Japanese Americans, did not understand them, did not understand the dispiriting impact of removal and incarceration on them, and saw Japanese religious and cultural activities in the most racial and hysterical light. Many of the military agencies saw the WRA as failing to understand the exigencies of war and dangerously sympathetic to Japanese Americans.

As a result of these disagreements, the recommendations of the JAJB became increasingly irrelevant over the course of its fifteen-month lifespan. The WRA came to understand that, as a practical matter, it had final authority to release Japanese Americans from its camps. Once the WRA released someone, that person could not be rearrested even if the JAJB had recommended against his release. By the fall of 1943, the WRA therefore began disregarding adverse JAJB findings with which it disagreed and making its own judgments on standards considerably more lenient than the JAJB's. At around the same time, the War Department formally shifted to the PMGO the authority to make decisions about which Japanese Americans qualified for employment in plants doing work important to the war effort.

The JAJB was formally dissolved in May of 1944.

For More Information

Muller, Eric L. American Inquisition: The Hunt for Japanese American Disloyalty in World War II . Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

Last updated June 15, 2020, 7:02 p.m..