Mike Lowry

| Name | Mike Lowry |

|---|---|

| Born | March 8 1939 |

| Died | May 1 2017 |

| Birth Location | St. John, Washington |

| More information... | |

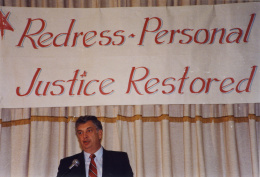

U.S. Congressman representing the Seattle, Washington, area who introduced the first legislation calling for reparations for Japanese Americans forcibly removed from the West Coast during World War II. Mike Lowry (1939–2017) later served as governor of the State of Washington from 1993 to 1997.

Early Life and Career

Michael Edward Lowry was born on March 8, 1939, in St. John, Washington, a small farming town around forty miles south of Spokane. He was the second of three children. When he was seven, the family moved to nearby Endicott, where he graduated from high school in 1957, part of a class of fourteen students. He attended nearby Washington State University in Pullman, graduating in 1962 with a degree in political science. After being turned away from the navy due to high blood pressure, he worked as a salesman and a building contractor. He also became involved in politics, working on the 1968 presidential campaign of Robert Kennedy and the 1968 gubernatorial campaign of State Senator Martin Durkan. Though Durkan's bid was unsuccessful, he offered Lowry a job on the staff of the Senate Ways and Means Committee and became Lowry's first political mentor. Lowry subsequently managed Durkan's unsuccessful 1972 bid for the governorship.

Lowry's first bid at an elected office came in 1973, when he challenged incumbent King County Executive John Spellman. Though he lost, the little-known Lowry received 42% of the vote. He won election in 1975 the King County Council, become the youngest member of the council at age 36 and swinging it to give the body a Democratic majority. He ran for the U.S. Congress in 1978 against Republican Jack Cunningham, who had won the seat in a 1977 special election. After winning a tight primary battle, he won the general election in the heavily Democratic district that included Seattle's primary African American and Asian American enclaves.

Redress Pioneer

At an October 1978 fundraiser, Lowry was approached by Seattle redress activist Henry Miyatake about supporting a redress bill if elected. Lowry agreed on the spot. He kept his promise upon taking office. His aides Ruthann Kurose and Kathy Halley worked with members of the Seattle Evacuation Redress Committee (SERC)—whose " Seattle Plan " called for individual monetary reparations for all those forcibly evicted by the federal government during World War II—to draft legislation. On November 28, 1979, Lowry introduced H.R. 5977, the World War II Japanese-American Human Rights Violation Redress Act, with twenty-four co-sponsors. Following the broad outlines of the Seattle Plan, the legislation called for reparations of $15,000 plus $15 per day incarcerated. However Japanese American legislators and the Japanese American Citizens League did not support the bill, having decided instead to pursue alternative legislation supporting a study commission. Though Lowry saw his bill as being compatible with the study commission bill, it died in the House Judiciary Committee, while the commission bill was eventually passed and signed into law, establishing the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC).

Lowry continued to support redress, speaking at the first Day of Remembrance in 1979 and appearing at the Seattle CWRIC hearings in 1981. After the CWRIC issued its report and recommendations, Lowry introduced H.R. 3387, the World War II Civil Liberties Violation Redress Act, on June 16, 1983, that included many of the recommendations, including the provision for $20,000 individual reparations. A second bill, sponsored by Texas Representative Jim Wright, was introduced on October 6, 1983, and Lowry called on his co-signers to transfer their support to that bill. Though redress legislation did not pass in this Congress, it was passed in the next one and signed into law on August 10, 1988, as the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 . Lowry was not present at the signing, his invitation having been mistakenly sent to William Lowry, a Republican representative from San Diego who hadn't even voted for the bill.

Later Career

Lowry proved to be an enormously popular Congressman, winning reelection four times, the last three times drawing over 70% of the vote. He became known for his constituent relations and frequent community meetings, his pointed criticism of the Ronald Reagan administration, his support of the environment, and for his big annual "shrimp-feed" fundraiser in Washington, D.C. After the death of longtime Senator Henry "Scoop" Jackson in 1983, Lowry ran for his seat, but was defeated in a run-off by former Governor Dan Evans. When Evans decided not to seek reelection, Lowry gave up his house seat to run again for the Senate in 1988, but suffered a narrow loss to Slade Gordon.

After a stint teaching at Seattle University, he ran for governor in 1992, winning the general election over Ken Eikenberry. Despite controversies over a tax hike during a recession, his support for free trade, and a new baseball stadium, he was a popular governor and was favored for reelection. However he chose not to seek reelection, due in part to sexual harassment charges raised by a former staffer in 1995. [1]

He was subsequently involved with housing and environmental organizations and frequently appeared at Japanese American community events and commemorations of the incarceration and of the Redress Movement . Mike Lowry passed away May 1, 2017.

For More Information

Chesley, Frank. " Lowry, Michael Edward 'Mike' (b. 1939). " HistoryLink.org.

" Guide to the Mike Lowry Congressional Papers, 1978–1988. " University of Washington Libraries.

Mike Lowry video oral history . Interviewed by Trevor Griffey, April 19, 2006. Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project.

Shimabukuro, Robert Sadamu. Born in Seattle: The Campaign for Japanese American Redress . Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2001.

" State of Washington Governor Mike Lowry. " Archived web site of Lowry as governor, ca. 1997. Washington State Archives.

Footnotes

- ↑ A investigation by a lawyer chosen by Lowry's office concluded that he had touched his accuser "in a way that she found offensive," but that his behavior stopped short of sexual harassment. Without admitting guilt, he later agreed to settle with her for $97,500. New York Times , March 26, 1995 and July 15, 1995, accessed on September 11, 2013 at http://www.nytimes.com/1995/03/26/us/report-finds-no-harassing-by-governor.html?src=pm and http://www.nytimes.com/1995/07/15/us/governor-is-settling-harassment-charges.html?src=pm .

Last updated May 1, 2017, 6:54 p.m..

Media

Media