Pomona (detention facility)

This page is an update of the original Densho Encyclopedia article authored by Konrad Linke. See the shorter legacy version here .

| US Gov Name | Pomona Assembly Center, California |

|---|---|

| Facility Type | Temporary Assembly Center |

| Administrative Agency | Wartime Civil Control Administration |

| Location | Pomona, California (34.0500 lat, -117.7500 lng) |

| Date Opened | May 7, 1942 |

| Date Closed | August 24, 1942 |

| Population Description | Held people from Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Santa Clara Counties in California. |

| General Description | Located at the Los Angeles County Fairgrounds (Fairplex) in Southern California. |

| Peak Population | 5,434 (1942-07-20) |

| Exit Destination | Heart Mountain |

| National Park Service Info | |

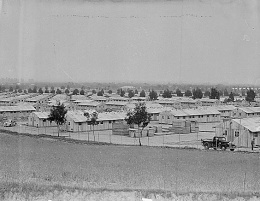

The Pomona Assembly Center was located on the Los Angeles County Fairgrounds (Fairplex), California, about thirty miles east of downtown Los Angeles and only twenty miles east of the Santa Anita Assembly Center . Most of its population came from Los Angeles, San Francisco and Santa Clara Counties in California. With a peak population of 5,434, Pomona was operational for 110 days, from May 7 to August 24, 1942. Almost all inmates were sent for long-term confinement to the Heart Mountain , Wyoming War Relocation Authority camp. The camp was afterwards used by the Third Battalion, 56th Quartermaster Regiment, which was already using the adjoining Pomona Fairgrounds.

Site History/Layout/Facilities

The site was part of an extensive fairgrounds that was the location of the first L.A. County Fair in October 1922, which attracted 50,000 visitors to the small city of Pomona. Subsequently more structures were added: a racetrack with a grandstand, several livestock and administration buildings as well as "the largest exhibit building in the world," seating 16,000. Attendance peaked at 265,000 in 1930, and declined after the Depression hit Pomona. After pari-mutuel wagering was legalized in California in 1933, allowing fans to bet on horse racing, attendance rose to over 330,000 as the Works Progress Administration (WPA) aided in the construction of more buildings. Most of these structures are still used to the present day. [1]

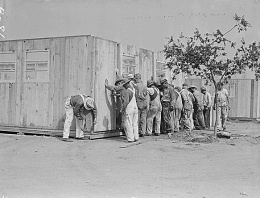

The construction of the camp started on March 21. The barracks were built on a field north of the grandstand and the race track, with only a few existing building being used to house the administration. Since few existing facilities could be used, costs for the Pomona detention facility totaled $1,068,000 (approximately $200 per inmate), more than other WCCA camp. [2]

When the camp's first manager arrived on April 7, one month prior to the camp's opening, the camp was 25 percent complete. Rainy weather during April delayed construction work. Construction was done by the United States Army Engineering Department (USED) and contractors, supported by WPA labor, which remodeled almost all buildings, partitioning, flooring, rewiring, installing additional toilets and providing shelving and cupboards. Seventy WPA man-months were consumed by this work. [3] On April 29, initial construction was completed and the army engineers turned the site over to the WCCA. However, construction work continued until May 25.

By the end of May, 309 barracks served as accommodations, each measuring 20 x 64 feet, subdivided into smaller apartments. Sixty barracks had six apartments each, 42 barracks had five apartments and 207 barracks had three apartments each. At its peak population of roughly 5,400 this equaled 74 square feet per person. (The WCCA's self-imposed standard was 200 square feet per couple).

The army issued 3,500 steel cots, 1,300 canvas cots, and 3,000 cotton mattresses. The remainder received tick mattresses to be filled with straw. "Physically able" persons were asked to leave their steel cots and cotton mattresses to the elderly and inmates with health problems. The main complaint with regard to housing, according to the camp manager's report, was the lack of mattresses and buckets. Rooms were empty except for the army cots and a single light bulb. [4] Years later, when Densho interviewed former inmates, several reported being housed in stables. However, there is no documentary evidence for this.

There were 11 laundry buildings, with 14 double laundry tubs in each laundry. There were 34 bath houses, each having seven showers (one shower head per 23 persons). There was a total of 36 latrine buildings, each measuring 20 x 28 feet. By mid-July the camp administration had contracted a laundry and cleaning service which the inmates could request at their own expense. [5] Latrine improvements done by the WPA included construction of footbaths, the addition of duck boards in front of the latrines, and erecting toilet stalls in women's latrines.

There were eight mess halls, each intended to serve 432 inmates. Each mess hall had a milk station operated by the health service. Breakfast was from 7 to 8 a.m., dinner from noon to 1 p.m., supper from 5 to 6 p.m. There was a separate mess hall for the hospital (seating 20) and another one for the camp administration (seating 40). An additional mess hall was used as a recreation building. The daily ration costs were given as 39 cents per person. Food was stored in five warehouses and two refrigerator cars, which were located in a fenced-off area. There were around 550 Japanese Americans and 10 Caucasians working in the mess section. [6] In July, a weekly mess hall competition was initiated which helped to improve the conditions. [7]

A drawback of the facilities in almost all "assembly centers" was the limited wiring capacities, which forced the administration to severely restrict the usage of electrical appliances by the Japanese Americans. This was, in fact, one of the major complaints by the inmates. [8]

There were two 8 x 8 feet sentry buildings at the camp entrance, in addition to fenced-off guard towers inside the camp boundary fence. The military police were housed in a fenced compound within the camp. Likewise, the administration area and the warehouses were fenced off within the camp. The visitor area, comprising several 16 x 16 feet buildings, shelters and benches, as well as another 8 x 8 feet sentry tower, was also fenced off near the main entrance. [9]

The inmates manufactured furniture and added shrubs and other plants for landscaping.

Camp Population

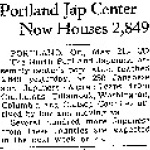

The camp was prepared to induct up to 1,000 by April 26. The first Japanese-American family arrived at Pomona on the afternoon of May 7. Two days later 72 Japanese Americans were inducted, and by May 25, 4,671 people had arrived. About 4,000 inmates of the Pomona Assembly Center came from Los Angeles, 750 from San Francisco's Japantown area, and 650 from Mountain View and Sunnyvale in Santa Clara County. The Los Angeles area inmates mostly came from three areas: about half came from areas east of downtown including Monterey Park, Whittier, and Monrovia, stretching east to the area near the camp. Most of the rest came from the Silver Lake/Echo Park area north of downtown, while a smaller group came from neighborhoods southwest of downtown.

| Exclusion Order # | Deadline | Location | Number |

| 32 | May 9 | South Los Angeles | 603 |

| 41 | May 11 | San Francisco Japantown | 736 |

| 42 | May 11 | Los Angeles: Silverlake area | 942 |

| 43 | May 11 | Los Angeles: Echo Park/Silverlake | 472 |

| 55 | May 15 | Whittier/Monrovia east to Pomona | 1,166 |

| 56 | May 15 | Monterey Park | 740 |

| 96 | May 30 | Santa Clara County: Mountain View, Sunnyvale | 657 |

Source: John L. Dewitt, Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 (Washington D.C.: U.S. Army, Western Defense Command), 363–66. Exclusion orders with fewer than thirty inductees not listed. Deadline dates come from the actual exclusion order posters, which can be found in The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement: A Digital Archive, Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley, http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_b016b01_0001_1.pdf and http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_b016b01_0001_2.pdf .

| Arrival Date | Arrival Time | Number | Via |

| May 7 | 4:30 pm | 6 | Personal car |

| May 8 | 3:30 pm | 72 | Personal car |

| May 9 | 11:00 am | 612 | Busses and cars |

| May 10 | 10:15 am | 1,130 | Busses and cars |

| May 11 | 11:30 am | 270 | Personal car |

| May 12 | 5:30 am | 734 | Train |

| May 14 | 9:45 am | 980 | Busses and cars |

| May 15 | 9:45 am | 850 | Busses and cars |

| May 19 | 8:30 pm | 2 | Personal car |

| May 20 | 11:00 am | 1 | Personal car |

| May 21 | 3:00 pm | 2 | Personal car |

| May 23 | 2:30 pm | 4 | Personal car |

| May 25 | 3:30 pm | 4 | Personal car |

| May 25 | Births to date | 4 |

Source: Clayton Triggs, Pomona Report for Secretary of War, May 27, 1942, Pomona Assembly Center, General Correspondence File, Pomona Center Manager, Secretary of War Report, Reel 180, NARA San Bruno. Note that this report was filed prior to the arrival of the Santa Clara group (Exclusion Order 96) a few days later, so this group is not represented in this table.

According to the May 27 report to the Secretary of War, the induction took an average of two minutes per family. Those arriving by car had their car impounded by an alien property clerk. Property was taken for inspection at arrival and could be reclaimed after the arrivals had undergone the induction procedure. This comprised a brief visual examination at a doctor's table, providing personal data, receiving mess tags and having a barrack assigned.

On July 20 the camp reached its peak population of 5,434 Japanese Americans. There were thirty-one births and three deaths during Pomona's operation. [10]

| Departure Date | Number |

| August 9 | 292 |

| August 15 | 529 |

| August 16 | 519 |

| August 17 | 530 |

| August 18 | 545 |

| August 19 | 507 |

| August 20 | 499 |

| August 21 | 542 |

| August 22 | 492 |

| August 23 | 392 |

| August 24 | 413 |

Source: John L. Dewitt, Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 (Washington D.C.: U.S. Army, Western Defense Command), 282–84.

Virtually all inmates were assigned to the Heart Mountain camp in Wyoming. On August 9, an advance group of 292 left the camp. Starting August 15, groups of about 500 left daily for the Heart Mountain camp.

Staffing

The camp's first manager, Raymond D. Spencer, arrived at Pomona on April 7, one month before the camp opened on May 7. His office, as well as the other administration buildings still under construction, were located at one end of a horse barn where telephones were available. Spencer selected the nucleus of the administrative personnel almost entirely from WPA staff, who selected the balance, again mainly from WPA sources. [11] Spencer, who was a WPA director for the Los Angeles district, was replaced on May 20 by Clayton Triggs who had previously supervised the establishment of the Manzanar Reception Center. Triggs remained director until the camp was closed down on August 24.

Other key staff:

Assistant manager: Ernest Wynkoop

Service director: Jack Conway

Recreation director: A.T. Richardson (also censor for the camp newspaper)

Works and Maintenance director: Bert S. Robards

Director of mess and lodging: Charles G. Patrick

Chief steward: Luigi Liserant

Hospital and health section head: Jack Abbott

Supervisor of supplies: Bernard Nixt

Fire chief: Frank J Maxwell

Police chief: Boyd F. Welker

Store manager: Jim Uyemura

[12]

Institutions/Camp Life

The army's curfew law required inmates to remain indoors from 10:30 p.m. to 6 a.m. A stricter 9:30 p.m. curfew was instituted at Pomona in June. In July, the WCCA classified Japanese language publications as contraband and had them confiscated. Notices written in the Japanese language (such as announcing church services) had to be submitted to the camp director first, with English translation, before they could be posted. [13]

Three weeks after the first Japanese Americans were inducted, the camp manager reported that 1,207 inmates had accepted work duties. By the end of July, there were 1,960 inmates working, a higher rate than in most other "assembly centers," where approximately one third of the population between the age of 18 and 65 were employed. [14] The camp manager recommended placing Japanese Americans in "key positions" in order to "increase efficient management," praising the "highly skilled" and "sincere evacuees" who were making up 96 percent of the staff. [15] According to WCCA policy, the wage scale was $8 per month for unskilled workers, $12 for skilled workers, and $16 for professionals.

The following chart from the May 27 report to the secretary of war shows the staff of the maintenance and operation crew, demonstrating that most work was done by the Japanese Americans themselves:

| Crew | Caucasian staff | Inmate staff |

| Division HQ | 2 | 3 |

| Maintenance and Operation office | 1 | 10 |

| Telephone switchboard | 4 | |

| Fire Department [16] | 6 | 21 |

| Plumbing | 1 | 3 |

| Electrical | 1 | 3 |

| Carpentry | 4 | |

| Painting and sign painting | 6 | |

| Streets | 33 | |

| Grounds | 14 | |

| Rubbish | 7 | |

| Janitor | 74 | |

| Total | 15 | 178 |

In housing, there were 32 inmates and two Caucasians employed, in the supply section there were four Caucasians and 101 inmates employed. [17] While on May 27, the camp director reported a total of about 600 Japanese Americans employed, the timekeeper's report of June 9 showed a total of 1,334 Japanese Americans employed—836 unskilled, 354 skilled, and 117 professional—with 39 Caucasians on the WCCA payroll. Hence in most fields inmates formed the backbone of center operations, and in some fields Caucasians remained supervisors only in name. For instance, George S. Ishiyama became head of the "information center" while W.Y. Hanaoka took over the hospital management. Wage disparities remained: The Caucasian police chief received a monthly salary of $300 (his officers received $175), while the inmate watchmen received $8. [18]

Although employing inmates was by and large a successful strategy it should be noted that by June 2, 56 workers had been dismissed or quit their jobs. Mess hall work was probably the most unpopular, and on July 9 the mess hall supervisor reported a shortage of workers in the mess halls. [19] Appealing to the competitive spirit and to improve sanitary conditions in mess halls, inmates and administration initiated a competition for the best mess hall, rating sanitary conditions and food quality. This was a strategy taken up in almost all temporary WCCA camps. In Pomona, each week a victor was determined who got a blue pennant. [20]

Community Government

Three weeks into the camp's existence, the camp manager reported that there was a "reliable leadership" conferring with the manager and his staff. They planned to have a "general representation" of the inmates and "the entire self-government organization completed within the ensuing week." [21] However, a self-government at Pomona was never established for two reasons: The first was a prohibitive WCCA policy: after the WCCA had received a report by Puyallup 's camp director, worrying that the increasingly assertive community government might "take over the center," the WCCA issued a series of restrictions, which slowed down the process and ultimately had the camp directors pick the representatives. [22] (For more on self-government, see the Puyallup and Tanforan articles.) The second obstacle was the complex, three-stage election procedure which inmates and administrators devised. In the first step, each of the 21 blocks elected three leaders, one of whom was appointed block leader by the camp administration. From this pool the inmates elected four ward leaders to form the advisory council. [23] By the time the advisory council had been elected, news arrived that inmates would soon be sent to a "relocation camp" and the self-government project was abandoned.

Education

With the population entering in May just as schools were letting out, there was no formal schooling set up. There was a nursery/elementary school for children aged four to ten starting in June but no plans for regular schooling, since the State Board of Education was expected to take over. Classes were held in two recreation halls off-hours, as there were no designated school buildings. Local and federal school officials made sure that students received their diplomas as the Pomona camp opened relatively late and students had missed only a few weeks. [24]

Ike Hatchimonji remembered receiving his graduation diploma at Pomona: "Because most of us had to drop out of school before graduation, and so they, somehow or other they arranged to have all the diplomas from various schools that we were in brought, and we had a ceremony outdoors. And so I received a little grammar school graduation diploma." [25] According the Hatchimoji, it was a very informal affair, no caps or gowns, one of the camp administrators handing over the diplomas during an open-air ceremony.

By July, carpentry classes for inmates aged twelve to sixteen were started, with 150 Japanese Americans signing up. Although the inmates had to purchase the tools themselves, it was hoped that these skills would benefit the community as their incarceration continued.

Medical Facilities

The hospital was essentially an army barrack, remodeled by WPA labor, which added hot water heating, desks, tables and benches, and curtains. Likewise, another barrack was converted into a first aid station by removing partitions, installing plumbing, and adding additional wiring and heating for hot water. A dental clinic opened in mid-July, operated by five dentists and a laboratory technician. [26] The 30-bed hospital included a contagious disease ward and an x-ray room, as well as a clinic. Medical supplies had to be approved by Dr. Bowdin from the USPHS.

The hospital staff included a number of qualified medical staff, among them W.Y. Hanaoka, supervising M.D.; Morton M. Kimura, M.D.; Benjamin Higa, M.D.; George Y. Takeyama, M.D.; Lillian Hanaoka, M.D.; Paul K. Ito, M.D.; Kazuto Kawahara D.D.S.; Kazuo Otamura, registered nurse (head nurse); Helen Kojo, registered nurse; and Michi Kajii, registered nurse; as well as 27 nurses and orderlies. The clinic was staffed by County Health Officer Dr. Chapman, County Health Sanitarian Dr. Ryan and Dr. Paul K. Ito. [27]

After three weeks in operation, a total of 58 patients had been hospitalized, 34 of whom had been released. There were 90 ambulance emergency calls and three patients in the L.A. County Hospital in Pomona for treatment. There were one case of mumps, fifteen cases of measles and four cases of tuberculosis. 563 persons had been treated as outpatients in the clinic. [28] According to the U.S. Army's Final Report there was an average of fourteen inpatients per week for the Pomona detention camp and a total of 1,430 outpatients treated in the period August 1 to August 21. There were 31 births and three deaths while Pomona was in operation. [29]

Policing and Unrest

Maintaining order was a small Caucasian police force, consisting of seven policemen plus Police Chief Boyd Welker. This was well below the average rate in WCCA camps, which was four Caucasian policemen to each 1,000 detainees. They were assisted by fifty Japanese American "auxiliary policemen." The camp newspaper repeatedly promoted understanding for their policing work, suggesting inmates see them as "good Samaritans and good neighbors." [30] The army later ordered daily head counts, which took place at least once a week at varying times, though mostly around 11 p.m. The inmates were allowed to recruit an additional thirty persons to take over the "disagreeable task" themselves. [31]

The camp manager reported no difficulties "as behavior of evacuees has been generally excellent." [32] In addition to patrolling the grounds, the police supervised the visitors' barrack, and escorted inmates to the hospital. Otherwise, the only major task was the inspection of luggage at the induction and later the emptying of the camp, which drew no major complaints. [33] Over the 110 days of the camp's existence only eleven arrests were reported to law enforcement agencies, which was well below the WCCA camp average. [34]

Library

The library opened shortly after induction and by May 27 held close to 1,700 books, from Pomona's public libraries and schools, as well as from private donations through the American Friends Service Committee. By June 16, there were 1,120 "residents" holding a library card. Popular items were magazines such as National Geographic , Life , Time , and Popular Mechanics and contemporary bestsellers Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell and Two-way Passage by Louis Adamic. On August 5, Librarian Aiko Yoshimura recalled all 1,921 books in the collection so they could be sent to the Heart Mountain WRA camp. [35]

Newspaper

Information regarding activities in camp was disseminated through the camp's newspaper, the Pomona Center News . Between May 23 and August 15 twenty-five issues appeared. The editor was Kei Hori who also wrote the editorial column "Crying Out Loud," often addressing the unpleasant sides of camp life. Six to eight pages in length, it was published twice a week, Tuesday and Friday, and exclusively in English. The paper was closely supervised by a "press relation representative," A. T. Richardson from the Pomona Progress Bulletin , who was to make sure that only favorable news was reported from the camp. Richardson visited Pomona twice weekly "to help edit the Center News." [36]

The first issue appeared on May 23, 1942. On the editorial board were Kei Hori, Haruo Imura, Michi Onuma and Edward Tokeshi. Estelle Ishigo, a Caucasian woman who had followed her husband, Nisei Arthur Ishigo, voluntarily into confinement worked as an artist for the paper.

Religion

Religious services were held in the two recreation barracks, seating about 185 people each. The first service took place on Sunday, May 24. Due to the limited space in the barracks, thirteen services were held successively: eight Protestant, four Buddhist and one Roman Catholic. Services included Sunday school for small children and for teenagers, fellowship meetings, and regular church service. They were held in the English and Japanese-languages, though Japanese was only allowed if the use of English prevented the congregation from comprehending the service. In such cases the camp director had to sanction the use of the Japanese language. The camp director estimated that about a third of the inmates took part in one kind of service or another. [37] By the end of June four barracks were needed to hold seventeen services for a total of about 2,700 inmates. Caucasian religious workers were allowed to enter the camp during the day. Prominent visitors included Dr. Frank Herron Smith, Bishop Reifsnider, and famous interdenominational preacher E. Stanley Jones who addressed the camp inmates during the Forth of July celebrations. [38]

Recreation

As in all "assembly centers," the army was interested in having a full recreation program to minimize social problems caused by forced inactivity. At the outset, however, even the most basic equipment was lacking as baggage limitations forced Japanese Americans to dispense with anything but the essentials for living. But with ingenuity and outside help the situation was improved to some degree.

As at most of the temporary detention camps, sports leagues were a highlight of camp life. The athletics section offered basketball, softball, judo, sumo, football, and volleyball; a women's section offered volleyball, softball, and ping pong; and the community offered ping pong and miniature golf. The facilities, however, severely limited the activities. There was, for example, only one ping pong table and eight manufactured paddles in the camp. After two weeks there were four baseball diamonds (one reserved for women), two volleyball courts, one judo pit, and a miniature golf course under construction.

To accommodate indoor activities, there were four barrack-size recreation halls, with a seating capacity of 200 each for ping pong and social games such as bridge. Recreation halls were also used for church meetings, discussion groups, talent shows, dances, and classes in flower arranging, wood carving, sewing, and embroidery, as well as piano lessons (there was one piano available), choral groups and band instruction, as "surprisingly many brought their instruments." [39] On June 11, a weekly series of recorded classical music concerts started in Barrack 249. The program included Bourree in A Minor by Bach, Symphony No. 5 in E Minor by Dvorák, the Song "Oh du, mein holder Abendstern" by Wagner, and Piano Concerto No. 3 in C Minor by Beethoven.

A motion picture fund was started, and the first movie to be shown was the comedy western Ruggles of Red Gap . Collecting $90 in donations at the showing, more movie nights were financed. [40]

There were some conflicts between the younger and the elder inmates over the use of the recreation halls, as they had to share the space with several activities taking place at the same time. The major complaints, were in particular the limited size of the recreation barracks, the missing outdoor seating facilities, and the lack of equipment. [41] Still, the camp manager estimated that approximately fifty percent of the population were engaged in one activity or another.

Store/Canteen

The store opened on May 26 and soon carried newspapers, cigarettes, candy and chewing gum, ice cream, oranges, a variety of non-alcoholic beverages, and toilet articles such as soap, razor blades, and toothpaste. As of May 27 there were sixteen inmates employed, and by July 11 the store employed 38 inmates, including store manager Jim Uyemura. The post office was in the same building as the center store and employed fourteen Japanese Americans.

The center store originally housed the draft board, as the camp director expected some 300 persons between the age of 20 and 65 to be registered. However, the registration never took place, as the army had stopped Selective Service in early 1942 on the grounds that Nikkei were not acceptable due to their ancestry. Once a week, a notary public from Pomona offered his service at the center store. [42]

Visitors

Visitors were received at a designated "visitor center," a fenced off area near the west entrance, consisting of a 8 x 8 feet sentry tower, sheltered benches and several 16 x 16 feet buildings. Visiting was regulated by an invitational pass system where inmates requested invitational passes from the administration, then sent a pass to prospective visitors for a specified day and time. The first time visitors were allowed was on May 24, two hours in the morning and two hours in the afternoon. On that Sunday 334 visitors were registered, meeting 583 Japanese Americans. [43] Due to the great demand daily visiting times were introduced, between 3 p.m. and 5 p.m., and the administration agreed to issue "pink passes" for visitors without invitations. An average of 460 passes was issued each week. Despite the tight security, Pomona's visiting system seems to have been one of the more efficient ones among the "assembly centers." [44]

Other

A postal clerk came from Pomona twice daily carrying the mail for the camp. A managing clerk, Ken Yamagi, and fifteen assistants staffed the post office, sorting and delivering the mail. Approximately 100 mail order packages were received daily at the camp's post office. [45]

The Fire Department included six white firemen and 21 inmates, organized in three companies, plus 26 volunteer firemen to assist on major fires. The first fire engine was lent by the L.A. County fire warden with the provision that only whites operate it. After the USED provided their own fire engine to the camp, only two of the six Caucasians remained. The firemen worked 44 hours per week, providing 24-7 coverage. The Pomona fire department, located 1.5 miles away, assured the camp manager they could arrive within ten minutes after being called.

To prove their patriotism the inmates started various initiatives to collect money for buying defense stamps and bonds. On Veterans Day, $150 was collected from the sale of poppies. A U.S.O. drive during the two weeks leading up to the Fourth of July garnered $700. The camp newspaper regularly publicized ads for war bonds. [46]

There were several inspections by outside agencies, such as the U.S.H.S., the WCCA leadership (Emil Sandquist, Col. Karl R. Bendetsen , Lt. Col. William A. Boeckel visited Pomona on July 16), and a Red Cross committee that visited the camp on July 20.

The camp manager praised the "excellent cooperation" between the inmates and the administration. Writing to the army that the inmates' "attitude towards conditions is philosophical and looking forward an end to the conditions," Triggs indicated that despite the cooperation the Japanese Americans were certainly not content with their situation. [47]

Chronology

April 7

Manager Raymond D. Spencer arrives and sets up headquarters. The camp is about 25% completed at this time.

May 7

The first Japanese American family arrives. Over 4,600 enter the camp over the course of the next eight days.

May 20

Raymond D. Spencer is succeeded by Clayton Triggs.

May 23

First issue of the

Pomona Center News

is published.

May 24

First Church Services take places.

June 8

550 attend first day of school.

June 11

First music appreciation hour, a weekly series of recorded music concerts, takes place.

June 14

Allan A. Hunter, Pastor of the Mount Hollywood Congregational Church is guest speaker at the Sunday service.

June 16

The outpatients clinic opens.

Helen Gahagan, a noted California liberal, visits the camp.

June 21

Reverend Paul Y. Watanabe, pastor of the Japanese Baptist Church in L.A. passes away in the L.A. General Hospital. His wife and three daughters are given permission to attend the funeral service.

June 23

First day of block leader elections, starting in blocks 1, 6, 10, 14, 18.

June 27

First open air movie night, showing

Ruggles of Red Gap

.

June 29

200 students receive their diplomas in an open-air ceremony.

Election of block representatives completed.

July 2

Representatives of the Student Relocation Council visit the camp to discuss with students ways to take up or continue their education in colleges outside the prohibited zone.

July 4

Fourth of July celebrations. During the previous two weeks inmates had donated approx. $700 to be handed over to USO officials in Pomona.

July 6

Dental office opened.

July 10

The first paychecks for inmates were issued.

July 17

Barber and beauty shop opened despite lack of supplies.

July 25

Arts and craft exhibit opens.

August 1

The camp newspaper officially announces that the Heart Mountain camp near Cody, Wyoming, will be the destination for most of its resident.

August 2

First sumo contest sees Iruharu Shimatsu winning the individual championship.

August 8

Obon Festival celebrated.

August 9

First advance group of inmates leave the camp. Last church services.

August 15

Evacuation proper starts with approximately 500 Japanese Americans transferred daily by train to the Heart Mountain WRA Camp.

August 24

Transfer completed. The 314th Military Police Escort Guard Company is withdrawn.

Quotes

On recreation activities, vaccinations and guard towers:

"It was really amazing to see all those barracks put up so quick. Part of the fairgrounds were toward the west side where La Verne Airport is, Brackett Field they called it, that was part of the athletic field later on. We had movies, the outdoor movies, after the sun went down, played a lot of softball. It was maybe a start of a vacation. You got to meet a lot of people but the part that hurt the most was being inoculated for typhoid and diphtheria, all of those were done by blunt needles and sterilized with either a candle or no, it was actually a alcohol flame. They'd wipe the needle and heat it up and then wipe it again and then shoot it in you. [Laughs] They kept doing it, I don't know how times they used the same needle."

"Yes, there were [guard towers]. It looked like a prisoner of war camp. They had floodlights that they can move around. I think the sentry was a lot heavier in Pomona than it was in Heart Mountain."

Ted Hamachi, 2010

[48]

On living conditions:

"[W]e lived in a barrack and like there was eight of us in one room and I know that my mother, we hung a blanket between my mother and my two sisters lived on the one side of the blanket and the rest of the male because they got embarrassed, you know, when they had to dress and whatever. So that's one thing I remember in the camp, what happened. I still remember I've never seen so many Japanese in all my life. [...]

"And the thing that I didn't like about it is, you know, living in one room and then you had to go to a bathroom, a central bathroom and a central mess hall to eat and all this. And I still remember in Pomona, the food was terrible because they just gave us C rations, you know, the army food until they can get... make arrangements to do things better. But until then it was terrible, I hated the food in Pomona, it was terrible."

John Nakada, 2010

[49]

On first impressions Pomona and food:

"[Pomona] was quite a disappointment. It was just dilapidated, hastily built barracks, not well built. And you've heard the stories about cracks in the walls, just single walls where you could see everything in the neighboring unit, open ceilings and such. And the bathing facilities and latrine facilities were very poor. And as well as the food and the way it was prepared, it was just very discouraging. [...]

"[A]t first [the food] was very bad because the cooks were Caucasians and I guess they didn't particularly care. They burned a lot of food. How do you burn oatmeal? They did, oatmeal. We just had a lot of things that were very... frankfurters, just raw frankfurters and a slice of bread or something like that. [...] I recall having some digestive problems. It was a long wait, the long waits in line. You've heard this story, it was very common. And it was quite hot and dusty, and we had to stand in long lines."

On having the family car impounded at arrival:

"Yeah, well, [the cars] were all in a fenced-off compound right outside of the camp area, and we could walk out in an open field, dirt field. We don't know why, but whoever's in charge of the military, there was a lot of soldiers who ran the place. They were able to literally race around with those cars and crash into each other. It would be called a jalopy derby, they didn't care if they, how much damage they inflicted on the cars. They were just raising dust and just going around and around, just having a great time. And I remember the nursery truck, the Hayami family, my good friend Walt, I was standing with him and we were watching this. It was amusing at that time. But when you consider what they were doing, allowed to be done, terrible. I don't think there was any compensation for those vehicles. They were just given to the military to destroy as they saw fit."

On receiving Caucasian friends in the camp:

"Mrs. Mills came, because they did allow visitors. They had an area, sort of a compound of high fences, double fences, you couldn't actually be in contact, you had to talk through a double, might have been a chain link fence. And, but we were, I remember Mrs. Mills brought some chicken one time, a box of chicken, and that story I remember very well. We took the box of chicken back after visiting was over, took the chicken back to the barrack unit, and then my brother and my sister and I just gorged ourselves with that. It was delightful to have chicken, fried chicken. But my mother saw that and she was overcome. So I remember that very distinctly."

On leaving Pomona for Heart Mountain:

"Yeah, well, again, the impact of this particular day when we had to walk down this dirt road toward the train, because that's where we boarded the train for Heart Mountain. There were soldiers on both sides of the road with shotguns and every few feet there was a soldier with a shotgun. It struck me at that time that, "Why are they doing this to us?" They're treating us like criminals. I felt, again, the impact was quite strong. I was beginning to realize what's happening, I guess. I guess that's the military way of doing things, but still, it's the impact that it had on me and everybody else. Very unnecessary."

Ike Hatchimonji, 2011

[50]

Aftermath

After Japanese Americans left the camp, the Third Battalion 56th Quartermaster Regiment, already using the Pomona Fairgrounds, expanded into the camp area. According to the Army's Final Report, "Ordnance Motor Transport" was the new agency using the camp. [51]

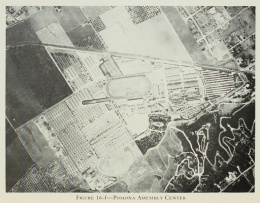

Today the area is a parking lot of the Fairplex where dragsters race and fair-goers park their SUVs. The grandstand and other fair buildings on the 1942 aerial photograph remain. Pomona Assembly Center was one of the twelve California temporary detention centers to share California Historical Landmark #934, so named in 1980, (Fairplex-State Historic Landmark #934-3). On August 24, 2016, a plaque marking the site of the assembly center was dedicated. [52]

For More Information

Allen, David. " Chronicling Internment, one story at a time. " Inland Valley Daily Bulletin , December 3, 2013.

Burton, Jeffery F., Mary M. Farrell, Florence B. Lord, and Richard W. Lord. Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites . Western Archeological and Conservation Center, National Park Service, 1999, 2000. Foreword by Tetsuden Kashima. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002. The Pinedale section of 2000 version accessible online at http://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/anthropology74/ce16f.htm .

Feeley, Francis. A Strategy of Dominance: The History of an American Concentration Camp, Pomona, California . New York: Brandywine Press, 1995.

Grant, Kimi Cunningham. Silver Like Dust: One Family’s Story of America’s Japanese Internment . New York: Pegasus Books, 2011.

Footnotes

- ↑ Fairplex website, accessed on May 4, 2019 at https://fairplex.com/aboutus/our-history .

- ↑ WCCA, undated fact sheet of the Pomona Assembly Center, National Archives II, RG 499, WDC, Unclassified Correspondence, Box 57.

- ↑ Clayton Triggs, Pomona Report for Secretary of War, May 27, 1942, Pomona Assembly Center, General Correspondence File, Pomona Center Manager, Secretary of War Report, Reel 180, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Triggs, Pomona Report for Secretary of War.

- ↑ Clayton Triggs, Weekly Report #14, July 8 to July 14, 1942, Pomona Assembly Center, General Correspondence File, Pomona Center Manager, Sandquist, E. Weekly Reports, Reel 180, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Triggs, Pomona Report for Secretary of War.

- ↑ Clayton Triggs, Weekly Reports #14, #15, #16, #20.

- ↑ Triggs, Pomona Report for Secretary of War.

- ↑ Triggs, Pomona Report for Secretary of War.

- ↑ John L. Dewitt, Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 (Washington D.C.: U.S. Army, Western Defense Command), 202.

- ↑ Triggs, Pomona Report for Secretary of War; Community Analysis Reports and Community Analysis Trend Reports of the War Relocation Authority, 1942-1946 , Reel 3. Washington, [D.C.]: NARA, 1984.

- ↑ Organization List, Pomona Assembly Center, General Correspondence File, Pomona Center Manager, Organization Chart and Lists, Reel 178, NARA San Bruno; Pomona Center News , various issues.

- ↑ Francis. A Feeley, A Strategy of Dominance: The History of an American Concentration Camp, Pomona, California (New York: Brandywine Press, 1995), 19, 29, 65; Pomona Center News , July 7, 1942.

- ↑ Clayton Triggs, Weekly Report report #16.

- ↑ Triggs, Pomona Report for Secretary of War.

- ↑ To be reduced to two Caucasians once the fire engine arrives. Present fire engine on loan by Los Angeles County with provision that only Caucasian engineers be employed.

- ↑ Triggs, Pomona Report for Secretary of War.

- ↑ Feeley, A Strategy of Dominance , 27-29.

- ↑ Pomona Center News , July 10, July 14, 1942; Feeley, A Strategy of Dominance , 34.

- ↑ Pomona Center News , July 10, 1942.

- ↑ Triggs, Pomona Report for Secretary of War.

- ↑ Narrative Report, Puyallup Assembly Center, May 26, 1942, quoted in Louis Fiset, Camp Harmony: Seattle’s Japanese Americans and the Puyallup Assembly Center (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2009), 143

- ↑ Pomona Center News , June 23, 1.

- ↑ Feeley, A Strategy of Dominance , 54-55; Pomona Center News , June 16, June 26, and June 30, 1942.

- ↑ Ike Hatchimonji interview by Martha Nakagawa, Segment 9, Los Angeles, California, Nov. 30, 2011, Densho Visual History Collection, Densho Digital Repository, https://ddr.densho.org/media/ddr-densho-1000/ddr-densho-1000-381-transcript-2146f03596.htm .

- ↑ Clayton Triggs, Weekly Reports #14, #15, #16; Pomona Center News , July 7, 2, July 17, 2.

- ↑ Triggs, Pomona Report for Secretary of War.

- ↑ Triggs, Pomona Report for Secretary of War.

- ↑ Dewitt, Final Report , 199–200, 202.

- ↑ Pomona Center News , June 26 and June 30, 1942.

- ↑ Feeley, A Strategy of Dominance , 23, 29-30.

- ↑ Triggs, Pomona Report for Secretary of War.

- ↑ Triggs, Weekly Reports #14, #15.

- ↑ Feeley, A Strategy of Dominance , 68-69; DeWitt, Final Report, 220-221.

- ↑ Pomona Center News , May 29, June 16, June 30, and August 5, 1942; Andrew B. Wertheimer, "Japanese American Community Libraries in America's Concentration Camps, 1942-1946" (PhD. diss., University of Wisconsin, 2004), 75-76.

- ↑ Pomona Center News , July 14, 1942; Feeley, A Strategy of Dominance , 70-71; DeWitt, Final Report , 213-214. All 25 issues have been digitized by Densho and are accessible online at http://ddr.densho.org/ddr-densho-193/ .

- ↑ Triggs, Pomona Report for Secretary of War.

- ↑ Feeley, A Strategy of Dominance , 65; DeWitt, Final Report , 212.

- ↑ Triggs, Pomona Report for Secretary of War.

- ↑ Pomona Center News , July 10, 1942.

- ↑ Triggs, Pomona Report for Secretary of War; Feeley, A Strategy of Dominance , 50-52.

- ↑ Triggs, Pomona Report for Secretary of War.

- ↑ Triggs, Pomona Report for Secretary of War.

- ↑ Triggs, Pomona Report for Secretary of War; Feeley, A Strategy of Dominance , 66-67.

- ↑ Pomona Center News , June 23, 1942, 4.

- ↑ Feeley, A Strategy of Dominance , 58-59, 69; Pomona Center News , July 7, 1942.

- ↑ Triggs, Pomona Report for Secretary of War.

- ↑ Ted Hamachi interview by Kirk Peterson, Segment 10, West Covina, California, Mar. 4, 2010, Manzanar National Historic Site Collection, Densho Digital Repository, https://ddr.densho.org/media/ddr-manz-1/ddr-manz-1-91-10-transcript-ccc9f43fb5.htm .

- ↑ John Nakada interview by Richard Potashin, Segment 11, Portland, Oregon, July 23, 2010, Manzanar National Historic Site Collection, Densho Digital Repository, https://ddr.densho.org/media/ddr-manz-1/ddr-manz-1-102-transcript-eb2179fe5d.htm .

- ↑ Ike Hatchimonji, 2011 interview by Martha Nakagawa, Segments 4 and 9, Los Angeles, California, Nov. 30, 2011, Densho Visual History Collection, Densho Digital Archive, https://ddr.densho.org/media/ddr-densho-1000/ddr-densho-1000-381-transcript-2146f03596.htm

- ↑ Final Report of Accomplishments and Activities , Clayton Triggs to Emil Sandquist, September 1, 1942, Pomona Assembly Center, General Correspondence File, Pomona Center Manager, Sandquist, E. Weekly Reports, Reel 180, NARA San Bruno; Dewitt, Final Report , 184.

- ↑ "Pomona Assembly Center!," The Bill Beaver Project, accessed on Sept. 14, 2020 at http://thebillbeaverproject.com/2011/09/25/pomona-assembly-center/ ; Burton, Jeffery F., Mary M. Farrell, Florence B. Lord, and Richard W. Lord. Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites (Western Archeological and Conservation Center, National Park Service, 1999, 2000; Foreword by Tetsuden Kashima, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002). The Pomona section of 2000 version accessible online at https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/anthropology74/ce16f.htm ; Rafu Shimpo , Aug. 25, 2016, 1.

Last updated Dec. 30, 2020, 8:36 p.m..

Media

Media