Roger Shimomura

| Name | Roger Shimomura |

|---|---|

| Born | June 26 1939 |

| Birth Location | Seattle, WA |

| Generational Identifier |

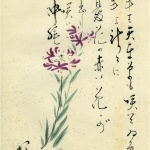

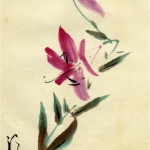

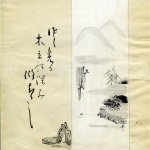

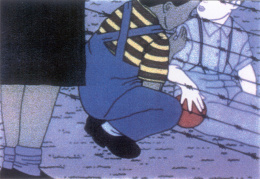

Sansei painter, printmaker, performance artist, teacher and collector Roger Shimomura (1939–) is best known for works that fuse pop art, the appropriated traditions of Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints, comic book characters and other pop culture symbols to deliver barbed messages about stereotyping and racism in America. Incarcerated along with his family in the Puyallup Assembly Center, Washington, when he was two, and in the Minidoka concentration camp in south central Idaho from the ages of three to five, the camp experience informs much of his work.

Early Life, Wartime and Incarceration

Born in Seattle, Washington, on June 26, 1939, to a pharmacist and a homemaker, Shimomura's grandparents arrived in the U.S. in the early 1900s. After the implementation of Executive Order 9066 , Shimomura's father was forced to give up his livelihood to enter prison camp with his family. His sister Carolyn was born in camp and died of meningitis when she was two. Many of the artist's works revolve around the Japanese American concentration camp experience, including the series "Diary" (1980) and "An American Diary" (2002–03), in which Shimomura incorporated selections of the translated diaries of his beloved grandmother Toku Shimomura. One of the most respected midwives in the Seattle area, Toku Shimomura delivered more than 1,000 babies, the last of whom was Shimomura himself.

Postwar Years, Beginnings as an Artist

The family returned to Seattle after the war, where Shimomura's father resumed his work at the Joseph Hart Pharmacy in Seattle. [1] Shimomura attended the highly diverse Garfield High School, where, he recalled, students formed social groups based on race and used racial epithets to distinguish one another. [2] As a child, his dream was to follow in his three maternal uncles' footsteps and become a graphic designer. Describing the atmosphere of his upbringing as "one of rebellion and tension and anguish," [3] he defied his father's wish that he become a doctor, or at least a dentist. Shimomura instead studied graphic design at the University of Washington, receiving his BA in 1961. He was required to join the Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC), which he described as "one of the most painful things for me." [4] Vowing to himself that he would not continue officer training and military science courses after the first two years, his father responded by enlisting the help of World War II veteran, 442nd Regimental Combat Team hero and old family friend Shiro Kashino to talk him out of his decision. A three-hour argument ensued, in which Kashino asserted that the Sansei generation must prove they, like their parents, were capable of being good officers. In the end, the veteran convinced Shimomura to sign up for advanced military science studies. Despite his reluctance, Shimomura excelled in the program and left the University of Washington a "Distinguished Military Graduate." He went on to serve in the U.S. Army Artillery (First Cavalry Division) from 1962 to 1964, stationed in Korea and Ft. Lewis, Washington.

Shimomura spent the next three years working as a commercial artist on jobs including the overall design for the Polynesian Pavilion at the 1964 New York World's Fair. However, his dislike for his adopted profession, especially working with clients, led him to take painting courses at the University of Washington, there "for the first time feeling the joy of what it was like to be a painter," he recalled. [5] Influenced by the burgeoning funk art movement of Northern California friends including ceramic artist Patti Warashina and the Bay Area figurative school, he realized that it was possible to combine painterly and pop imagery.

At Syracuse University, where Shimomura received his MFA in 1969, he also immersed himself in filmmaking and experimented with performance art. A lifelong collector, starting with bottle caps and handmade scooters, he began paying for his finds, including cardboard food advertisements, pre-1940s Disney memorabilia and vintage Coke machines. [6]

From 1969 to 2004, Shimomura served as a professor of art at the University of Kansas in Lawrence, Kansas. There, he made his name as an artist and received numerous awards and recognitions.

Works and Themes

Shimomura has noted that as a longtime resident of the Midwest, albeit based in a liberal academic environment, daily interrogations into his place of origin and assumptions that he was a foreigner could not help but shape his view of the Japanese American perceived as "other" in his or her native country. This, combined with his secure position in an institution that supported his creative efforts, allowed him the opportunity to find his voice as an artist. In the early 1970s he began adopting the pictorial language of traditional and widely recognized Japanese woodblock prints. In 1971 he conceived Oriental Masterpiece #1 , which included a ukiyo-e -style Mt. Fuji, a courtesan and a devil. Shimomura described it as "sort of comic surrealism." When viewers welcomed the new direction because now the work "looked like the artist," he says, "I recognized the full creative potential of my ethnic identity to my art." [7]

Shimomura began exploring the theme of the World War II concentration camps with his series Minidoka (1978–79), paintings focused on the colorful, flat style of ukiyo-e and pop art. Containing only subtle references to the concentration camp experience, Shimomura asserted that first and foremost an artist must be able to sell his work. He developed a style at once accessible and appealing, gradually adding cartoon icons and comic book characters to create works that were visually arresting and narratively ambiguous cultural mash-ups. Shimomura's adoption of ukiyo-e and pop art styles has drawn comparisons to his contemporary, artist Masami Teraoka. Appealing to a generation weaned on Mickey Mouse, Superman, Dick Tracy, and Bruce Lee movies, he inserted subtle and later more open challenges to the racist undertones that he encountered in America.

In "Diary" (1980) and "An American Diary" (2002–03) he mined the diaries of his maternal grandmother. The performance art pieces "Seven Kabuki Plays" (1985–87) were the result of his realization that performance was the only medium inclusive enough to allow him portray the treasure trove of poems, songs, and short stories that Toku Shimomura had also written. In the series Minidoka on My Mind (2006–10), Shimomura was ready to address the camp theme more directly, in "huge, in-your-face paintings" [8] that are frank in their depiction of barren and harsh camp conditions. In his 2012 painting, "Not Pearl Harbor," Shimomura conflated post-September 11 racial stereotypes with those in the wake of Pearl Harbor, depicting caricatures of Japanese wearing turbans and Taliban-style facial hair. In American Knockoff (2006–13) he explored how the physical appearance of Asian Americans affects how other people perceive them, noting, "because of wars, because of exclusion and so on, it is not a comfortable identity to be wearing...not only inaccurate but it's frequently insulting." [9] In the painting "An American in Disguise," Shimomura painted a portrait of himself wearing a traditional Japanese kimono over a Superman t-shirt.

Shimomura has noted that his art is neither therapeutic or cathartic. "Lots of Asian artists are doing beautiful stuff about their culture, but I'm not into that," he said. "I'm what someone once called that stick in the eye: Don't forget, don't forget." [10]

Since retiring from teaching, Shimomura has maintained an active exhibition and speaking schedule, including 15 retrospective exhibitions, the last at New York University’s Asian/Pacific/American Institute in spring 2013. He has donated his grandmother’s diaries and other family memorabilia to the Smithsonian American History Museum and his personal papers to the Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Art. He will also soon donate his large collection of camp memorabilia to the American History Museum. In 2008 he donated his 2,000 collectibles depicting Japanese and Chinese stereotypes to the Wing Luke Museum of the Asian Pacific Experience in Seattle. In 1994 he was designated a Distinguished Professor at the University of Kansas where he taught for 35 years, and was cited as a Distinguished Alumnus at the University of Washington in 2006.

For More Information

DeVuono, Frances. "Roger Shimomura at Greg Kucera Gallery." Artweek , 35:4 (May 2004), 26.

Diaz, Rodrigo. " Roger Shimomura at the San Jose Museum of Art." Artweek , 32:2 (February 2001), 18.

Farr, Sheila. "Internment as Seen by a Boy and Grandmother." Seattle Times , December 16, 2001.

Goodyear, Anne Collins. "Roger Shimomura: An American Artist." American Art , 27-1 (Spring 2013), 70-93.

Hallmark, Kara Kelley. "Roger Shimomura (1939- ), painting, printmaking, and performance art (Japan)." In Artists of the American Mosaic: Encyclopedia of Asian American Artists , Westport, Ct.: Greenwood Press, 2007.

Lippard, Lucy. "Roger Shimomura: Stereotypes and Admonitions." Seattle, Greg Kucera Gallery, 2004.

O'Sullivan, Michael, "Shimomura's Stark Reminders." Washington Post , July 7, 2000, WW, 48.

Shimomura, Roger; Lippard, Lucy R.; Nakane, Kazuko, Corwin, Nancy A.; Foresman, Helen. Roger Shimomura, Delayed Reactions: Paintings; Prints, Performance and Installation Art From 1973 to 1996 . Lawrence, Kansas, Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas, 1995.

Shimomura, Roger. An American Diary: January 16-February 13, 1999 , video. New York, Steinbaum Krauss Gallery, 1999.

Shimomura, Roger; Lew, William W.; Daniels, Roger; Rudolph E. Lee Gallery; et al. Minidoka Revisited: The Paintings of Roger Shimomura . Clemson, South Carolina, Lee Gallery, Clemson University; Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2005.

Shimomura, Roger; Uradomo-Barre, Stacey. Yellow Terror: The Collections and Paintings of Roger Shimomura . Seattle, Wing Luke Asian Museum, 2009.

Shimomura, Roger; Ahivers, Ben; Higa, Karin M.; Daniels, Roger. Shadows of Minidoka: Paintings and Collections of Roger Shimomura . Lawrence, Kansas, Lawrence Arts Center, 2011.

Roger Shimomura, artist website.

Stamey, Emily; Shimomura, Roger; Foresman, Helen. The Prints of Roger Shimomura: A Catalogue Raisonné, 1968-2005 . Lawrence, Spencer Museum of Art, the University of Kansas; Seattle, in association with the University of Washington Press, 2007.

Footnotes

- ↑ Email exchange with Roger Shimomura, December 30, 2013.

- ↑ Anne Collins Goodyear, "Roger Shimomura: An American Artist," American Art 27:1 (Spring 2013): 71.

- ↑ Goodyear, "Roger Shimomura," 76.

- ↑ Goodyear, "Roger Shimomura," 75.

- ↑ Goodyear, "Roger Shimomura," 78.

- ↑ Talk by Roger Shimomura, Asian/Pacific/American Institute New York University, February 13, 2013.

- ↑ Goodyear, "Roger Shimomura," 82-83.

- ↑ Goodyear, "Roger Shimomura," 86.

- ↑ Goodyear, "Roger Shimomura," 73.

- ↑ Michael O'Sullivan, The Washington Post, July 7,2000, WW, 48.

Last updated Jan. 16, 2024, 1:31 a.m..

Media

Media