Sueo Serisawa

| Name | Sueo Serisawa |

|---|---|

| Born | April 10 1910 |

| Died | January 16 2004 |

| Birth Location | Yokohama, Japan |

| Generational Identifier |

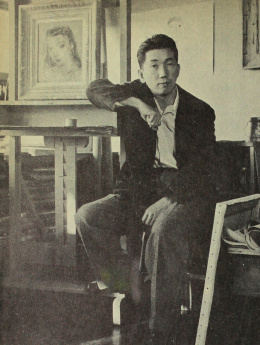

Sueo Serisawa (1910-2004) was a noted

Issei

painter, printmaker, and educator who was an active part of the California art scene.

Early Life and Filmmaking

Issei painter Sueo Serisawa (1910-2004) was born in Yokohama, Japan, on April 10, 1910. His father, Yoichi Serisawa, was a painter who studied with Hashimoto Gahō (who was considered one of the last masters of the Kanō school of painters) at the Japan Academy of Fine Arts (Tokyo Imperial Art Academy). Recognizing his son's talent, Yoichi began Sueo's art education at an early age. [1] Sueo's brother, Ikuo, was born two years later, on May 15, 1912. The family immigrated to Seattle, Washington, in 1918, then moved to Long Beach, California, in 1921, when Sueo was eleven. Once he was enrolled in public school, he began studying art at Long Beach Polytechnical High School, under the wing of the school's art teacher, George Barker, who encouraged his prodigious artistic talents. [2] His father Yoichi supported the family working as a calligrapher and commercial artist, but died from lung cancer in 1927. This unexpected tragedy led his mother to return to Japan, leaving the two teenage brothers in California. Following his high school graduation in 1932, Serisawa enrolled at Los Angeles' Otis Art Institute, where he studied under the New York realist painter, Alexander Brook.

Meanwhile, his younger brother Ikuo was passionately pursuing photography and filmmaking. In 1934, the two brothers collaborated (Sueo directed while Ikuo worked as cameraman) on a documentary-style film titled Nisei Parade about three young Nisei men and a young woman, with Southern California celery fields, the vegetable markets of Downtown LA, the hotel rooms and pool halls of Little Tokyo, and the waterfronts of San Pedro as their background. Although the film was silent, it had subtitles in both English and Japanese. In a 1963 column in the Pacific Citizen , Larry Tajiri wrote that among the actors in "Nisei Parade" were the Tanaka sisters of Long Beach, (who later married the Serisawa brothers,) Tib Kamayatsu, Pete Takahashi, and Alice Iseri. According to the same article, Tajiri was also the writer of the film's titles. [3] The film was previewed at the Miyako Hotel in December 1934 before it opened to the public in 1935. In the spring of 1935, the two brothers travelled a print of the film on a special screening tour at numerous Northern California community venues. Nisei Parade was praised for its photographic excellence by Hollywood technicians, including director Fritz Lang, who saw it at a preview. [4] The film was awarded an honorable mention for documentaries in the 1935 ASCE Amateur Movie awards. According to Pacific Citizen columnist Larry Tajiri, the only print of the film went to a photo supply dealer who had provided film and other materials to the producers, but this print has not resurfaced and is considered lost. [5] On October 18, 1937, he married Mary Tanaka, one of the main stars of Nisei Parade ; their daughter, Susan Eiko Serisawa, was born on February 25, 1941.

An Emerging Artist

By 1940, Sueo Serisawa's career was in full bloom and he began winning prizes and recognition around Southern California for his landscape, still life, and figure paintings, including the Award of Honor of the Foundation of Western Art and honors at the Fine Art Gallery in San Diego. Los Angeles Times critic Arthur Millier called Serisawa's painting "Nine O'Clock News," painted on the day Germany invaded Poland in 1939, "a young man's masterpiece." [6] In 1937, Serisawa had his first one-man show of portraits and landscapes done in oils at a gallery in Long Beach, and his painting titled "Backstreet," a Little Tokyo scene, won first prize at the Laguna Beach art salon, and then honorable mention at the Pomona County Fair. (Drawing on his experience in Little Tokyo, Serisawa also produced "A Second Generation," a portrait study of Issei and Nisei.) That same year, his work was featured in an exhibit of art by "California oriental painters" at the Foundation of Western Art in 1937. In 1939, his still life "The Three Pears" was featured in the Invitational Southern California art exhibit in San Diego's Balboa Park, and the following year, he exhibited work alongside Nisei painters Benji Okubo and Hideo Date in a show at the University of Southern California's Harrison Gallery. Soon after, he held a solo exhibition at the Dalzell Hatfield Galleries, located in the city's Ambassador Hotel. Hatfield would remain a prominent dealer and supporter of his work. In October 1940, Serisawa's painting of a church in a summer landscape was featured in the eighth annual Foundation of Western Art's "Trend" Show and another work won second prize at a exhibition held at the California State Fair. In December 1940, he was awarded the Western Foundation of Arts Medal as the most promising young Southern California artist.

The following year, he was similarly productive and continued garnering awards and attention throughout the state. In February 1941, he held a solo oil painting exhibition at Scripps College. The following month, he joined in the annual exhibit of art at the Oakland Art Gallery (today's Oakland Museum of California) alongside such artists as Miné Okubo and Henry Sugimoto . In September, his painting, "A Portrait of a Singer" (a study of Nisei soprano Tomi Kanazawa), exhibited at an invitational art exhibit of California Paintings at the Los Angeles County Fair at Pomona and one of his watercolors won first prize at a San Diego exhibition. Meanwhile, Serisawa's work began to attract the attention of Hollywood: MGM composer and producer Arthur Freed commissioned him to do portraits of performers Ann Sothern and Judy Garland for the studio, and requests were made for art instruction.

At the age of thirty one, he was a featured artist-of-the-month with a solo show at the Los Angeles Museum, which ironically opened on December 7, 1941. The Los Angeles Times reviewed the exhibit, but Serisawa was forced to abandon his career and life in California after U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 , which effectively pushed Serisawa, his wife, and newborn daughter out of the state. The Serisawa family "voluntarily" relocated themselves outside of the military zones forbidden for Japanese and Japanese Americans to avoid incarceration and settled in Colorado for a year, where their second daughter, Margaret, was born. They then spent a year in Chicago, where he studied for a short period at the Art Institute of Chicago. His brother Ikuo was also in Chicago and had set up at commercial photography studio before settling in Greenwich Village in New York City in 1943. [7] In New York, Serisawa developed friendships with other important artists including Yasuo Kuniyoshi . He was able to exhibit twice while living in New York at the Lilienfeld gallery. Serisawa was also included in a major exhibition of Nisei artists held at the Boston Public Library in June 1945, that included ten artists who created work in the World War II American concentration camps as well as sixteen Nisei artists who lived on the East Coast for many years. This exhibit was organized as a joint project between the Boston WRA office and the JACL Eastern office. In 1947, he and his family moved back to Los Angeles, where he continued to paint in increasingly impressionistic, abstracted styles and was soon represented by one of the West Coast's most renowned galleries, Dalzell Hatfield. He also taught art classes at the Kann Institute of Art (1948-50), Claremont College (1948), and Scripps College (1950-51). His international reputation and popularity amongst Hollywood celebrities even led to private classes for celebrities such as Edward G. Robinson, Claire Trevor and Frances Marion.

Later Career

He collaborated with his brother Ikuo on a second short color film on Japanese art entitled Bunka , which won an award at the 1956 Golden Reel film festival in Cleveland. Prints of Bunka were reportedly purchased by a number of art museums and added to their permanent collections. [8]

Serisawa became a naturalized citizen of the United States in 1953 and returned to Japan for the first time in 1955, accompanied by watercolorist Millard Sheets, which would prove to have an inspirational influence on his painting. Upon his return to the United States, Serisawa began what he called "Zen painting," merging his abstractions with Japanese forms. In 1958, he was commissioned by the Huntington Library to restore the ceremonial teahouse in their Japanese garden. [9] In the ensuing years, Serisawa altered his style from European-style expressionism to heavy reliance on use of Japanese abstract elements. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, he increasingly explored traditional Japanese forms including calligraphic works, woodblock prints, and gold and silver leaf sumi-e paintings. In the mid-1970s, Serisawa re-married and moved to the mountain town of Idyllwild, California, where he began to explore natural themes and forms, blending sumi-e and watercolor techniques.

A range of his work can be found in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Museum of Modern Art, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Smithsonian Institution, and the San Diego Museum of Art, among other national and international museums and galleries.

Serisawa died at age 94 on September 7, 2004, in San Diego, California.

For More Information

Chang, Gordon H., Johnson, Mark Dean, and Karlstrom, Paul J. editors. Asian American Art: A History, 1850-1970 . Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 2008.

Davis, Judson. Sueo Serisawa Retrospective Exhibition Catalogue . Los Angeles: Japanese American Cultural and Community Center, 2000.

Millier, Arthur. "Sueo Serisawa: An Account of the Inner Development of a Young American Painter." American Artist (June 1950).

Robinson, Greg. " Sueo and Ikuo Serisawa's Lifelong Dedication to the Arts. " Nichibei Weekly , Feb. 1, 2018.

Serisawa, Sueo, and Marsha Serisawa. CAABS project interview. May 17, 2000. Idyllwild, Calif. Transcript, Asian American Art Project, Stanford University.

Wechsler, Jeffrey, ed. Asian Traditions/Modern Expressions: Asian American Artists and Abstraction: 1945-1970 . Abrams in association with the Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, 1997.

Wind in the Pines: Serisawa's Poetry in Painting . Film. Los Angeles: Japanese American Cultural and Community Center and Naljoropa Productions, 2000.

Footnotes

- ↑ Greg Robinson, "Sueo and Ikuo Serisawa’s Lifelong Dedication to the Arts," Nichibei Weekly , Feb. 1, 2018, https://www.nichibei.org/2018/02/the-great-unknown-and-the-unknown-great-sueo-and-ikuo-serisawas-lifelong-dedication-to-the-arts/ .

- ↑ Robinson, "Sueo and Ikuo Serisawa."

- ↑ Larry Tajiri, "Vagaries: Thirty Years Ago," Pacific Citizen , Apr. 12, 1963, 3.

- ↑ "Nisei Parade Depicts Life Photographed Against Variegated Scenes of Japanese Life in California," Shin Sekai Nichi Nichi Shinbun , Mar. 14, 1935, 1.

- ↑ Robinson, "Sueo and Ikuo Serisawa."

- ↑ Gordon H. Chang, Mark Dean Johnson, and Paul J. Karlstrom, editors, Asian American Art: A History, 1850-1970 (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 2008).

- ↑ "Nisei Parade...," Pacific Citizen , Apr. 1, 1944, 5. "Before evacuation, Sueo Serisawa was one of California's outstanding painters. Today he is a Chicagoan, after having lived Colorado Springs and Denver during the past two years."

- ↑ Larry Tajiri, "Vagaries: The Serisawa Brothers," Pacific Citizen , Sept. 12, 1958, 3.

- ↑ "Centennial Timeline", https://www.huntington.org/timeline-item/centennial-timeline-1958 .

Last updated Nov. 16, 2020, 3:45 p.m..

Media

Media