Takuichi Fujii

| Name | Takuichi Fujii |

|---|---|

| Born | September 26 1891 |

| Died | July 16 1964 |

| Birth Location | Hiroshima, Japan |

| Generational Identifier |

Takuichi Fujii (1891-1964) immigrated to Seattle in 1906 and became a well-recognized artist in the 1930s. He and his family were incarcerated during World War II, first at the Puyallup temporary detention site and then at the Minidoka War Relocation Authority camp. After the war he resettled in Chicago , where he continued painting until the end of his life. The outstanding feature of his artistic production is an illustrated diary and some 130 related watercolor paintings of his wartime experience. The distinguished historian Roger Daniels has called Fujii's diary "the most remarkable document created by a Japanese American prisoner during the wartime incarceration." [1]

Early Life and Artistic Recognition

Fujii was born in Hiroshima in 1891 and attended school there through the eighth grade, including two years of private study in brushwork, or ink painting. [2] Little else is known of his youth in Japan. In 1906, a few days after his fifteenth birthday, he sailed for Seattle where his father and an older brother were working, and would soon return to Japan. He eventually found work at Main Fish Company in Nihonmachi, where in eight years he rose to salesman, and by 1917 he opened his own business as a fish merchant. On a return visit to Hiroshima in 1916, he met and married Fusano Marumachi (1896-1995). They had two daughters, Satoko (Satoko Mary Rose Fujii Kita, 1917-1999) and Masako (Masako Fujii Nelson, 1919-ca. 2000).

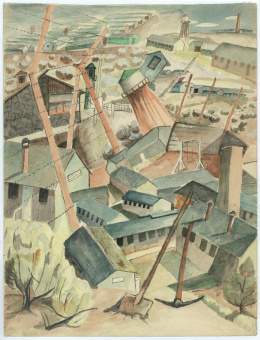

The first record of Fujii's artistic production came in 1930, when his oil painting was selected for the Northwest Annual juried exhibition. The next year his entry won an award. Although there is no evidence of Fujii's earlier engagement, his command of painting tells of his artistic affiliation in the community. Seattle's Nihonmachi had a high level of artistic activity of many kinds; painters working the Western tradition had exhibited prominently in the city since the early twentieth century. Fujii exhibited his work frequently in Seattle and the San Francisco Bay Area in coming years. He painted in an American realist style with attention to modernist currents at the time. When in 1935 some of the city's progressive artists formed the Group of Twelve to advance "the best painting in the Northwest," Fujii, together with Issei painters Kenjiro Nomura and Kamekichi Tokita , was invited to join. [3] The three were among ten artists chosen to represent Washington State at the First National Exhibition of American Art in New York in 1936.

Fujii's artistic rise was interrupted when, for unknown reasons, he and his family moved to Chicago for two years. He exhibited there once, at the Art Institute of Chicago's regional juried annual. In 1939 he and Fusano returned to Seattle, while their young adult daughters remained in Chicago but would return home before 1942. The couple began a new business together, the Mary Rose Florist shop. Fusano assumed primary responsibility, allowing Fujii time to paint, and once again, he participated in regional annual exhibitions.

World War II Incarceration and Artwork

Fujii, his wife, and daughters, along with nearly all others of Japanese ancestry on the West Coast, were incarcerated during World War II. They were confined first at the Puyallup temporary detention site on the Washington State Fairgrounds thirty miles south of Seattle, and in August 1942, sent to the Minidoka incarceration camp in Idaho. Their daughters left Minidoka on work release in 1943, while Fujii and his wife remained there until the camp's closing in October 1945.

Sometime in May 1942, Fujii began an illustrated diary, which eventually reached nearly four hundred pages that span the family's forced removal from Seattle to the closing of Minidoka. Each ink drawing except the final few is accompanied by text, typically a brief caption identifying a place or event, and elsewhere, a distilled and evocative meditation. Step by step in the opening pages, Fujii describes in spare terms his move from freedom to incarceration. The diary is replete with images of the barbed wire fence, armed soldiers, and watchtowers as he methodically surveys Puyallup and then Minidoka. He pictures the daily routine, kinds of work and leisure activities, but the fact of confinement predominates. Throughout the diary, Fujii declares himself a witness as he describes his viewpoint in surveying the grounds at Puyallup and Minidoka and pictures himself sketching in public view. In chronological scope alone, it may be the most extended visual documentation of the incarceration.

Art historian Sandy Kita, the artist's grandson and the diary's primary translator, characterizes Fujii's project as an art diary in the Japanese literary tradition and links it to the long history of combining text and image in Japan. [4] Rather than a daily account of experiences, Fujii's diary, like poetry, is a means of conveying thoughts and emotions one would not reveal in other circumstances. It also represents his perspective as an Issei man. At Puyallup, for example, Fujii declares that the Japanese American Citizens League had cooperated with the Army's Wartime Civil Control Administration and "did everything in this camp," implying if not stating the loss of the Issei's customary authority. In sequential pages, he pictures in subtle contrast the leisure activities of the Issei and Nisei. Elsewhere he alludes to generational tensions arising from questions of loyalty. Throughout the diary, text and image together intensify meaning to reveal a more complex story than either does alone.

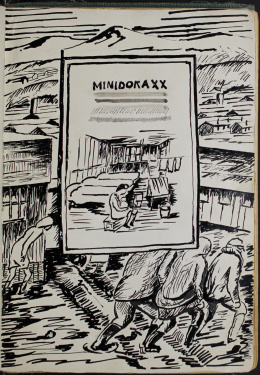

In addition to the diary Fujii produced some 130 watercolors and larger ink drawings that are related to the diary. Some replicate diary compositions, while others are new views. Many of the watercolors have an immediacy that suggests they were made on site, while others could have been painted in later years as he reflected on the wartime experience. Forty-two of the larger watercolors were found matted as if for exhibition and stored in a handmade portfolio, although there is no definitive evidence of their having been displayed. [5] The diary drawings also served as the basis for Fujii's illustrations for a yearbook-style publication, Minidoka Interlude , produced by a Nisei-led team in 1943. [6] Additionally, Fujii produced several oil paintings and carved objects, some for exhibitions held at Minidoka and nearby Twin Falls, and some of more personal character.

Postwar

With the closing of Minidoka, Fujii and his wife moved to Ogden, Utah, where their older daughter, by then married, had moved on work release. They made a final move to Chicago in 1947, and by 1948 the entire family was reunited there. The family soon included two young grandsons, the younger of whom, Sandy Kita (b. 1950), would become a scholar of Japanese art and the translator of Fujii's diary. They lived in the Near North neighborhood, part of a large Japanese American community that developed in wartime as a result of the War Relocation Authority 's dispersal and resettlement policy. Fujii found work in a lithography shop but shortly retired to family life. He continued to paint, picturing the seasonal landscape outside his home and experimenting with various modes of abstraction. He exhibited twice in the late 1950s in large nonjuried exhibitions at Navy Pier. In the last years of his life, his pursuit of abstraction culminated in a series of black and white abstract expressionist paintings. He died of complications of lung cancer in 1964.

Fujii's work during and after the war was unknown until the publication of art historian Barbara Johns's The Hope of Another Spring in 2017 followed by a touring exhibition. [7] Even before he died, Fujii's whereabouts and achievements were unknown to those in Seattle who once knew him; in 1956 he was reported to have returned to Japan. After his death in Chicago, Fujii's diary and artwork from 1942 to 1964 were stored by three generations of his family—his wife, his older daughter, and his grandson, Sandy Kita. Kita recognized the value of the collection and undertook the translation of the diary. Half of the diary in translation is reproduced in Johns's book.

For More Information

Johns, Barbara. The Hope of Another Spring: Takuichi Fujii, Artist and Wartime Witness . Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2017.

———. Signs of Home: The Paintings and Wartime Diary of Kamekichi Tokita . Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2011. [Includes the translated diary of a Seattle Issei incarcerated at Puyallup and Minidoka.]

Minidoka Interlude: September 1942–October 1943 . Hunt, Idaho: Minidoka Relocation Center, 1943. Reissued with an introduction by Tom Takeuchi. Gresham, Ore., privately published, [ca. 1990]. Reprint available from Friends of Minidoka, www.minidoka.org.

Kenjiro Nomura: At Artist's View of the Japanese American Internment . Essay by June Mukai McKivor. Seattle: Wing Luke Asian Museum, 1991. [A Seattle Issei whose paintings depict Puyallup and Minidoka.]

Footnotes

- ↑ Roger Daniels, "Foreword," in Barbara Johns, The Hope of Another Spring: Takuichi Fujii, Artist and Wartime Witness (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2017), viii.

- ↑ This article is based upon Johns, The Hope of Another Spring . Fujii left almost no personal papers except the diary and artwork.

- ↑ Some Work of the Group of Twelve (Seattle: Dogwood Press, 1937).

- ↑ Sandy Kita, "Introduction to the Diary: The Nature of the Work and of Its Translation," in Johns, The Hope of Another Spring , 131-36.

- ↑ Johns, The Hope of Another Spring , 107.

- ↑ Minidoka Interlude: September1942-October 1943 (Hunt, Idaho: Minidoka Relocation Center, 1943).

- ↑ See notes 1, 2 above. The exhibition Witness to Wartime: The Painted Diary of Takuichi Fujii , curated by Barbara Johns, opened at the Washington State History Museum on September 16, 2017 and at the time of this writing will tour nationally through 2021. Fujii's paintings of the 1930s were first brought to renewed public attention by Mayumi Tsutakawa in Turning Shadows into Light: Art and Culture of the Northwest's Early Asian/Pacific Community , edited by Tsutakawa and Alan Chong Lau (Seattle: Young Pine Press, 1982), and They Painted from Their Hearts: Pioneer Asian American Artists , edited by Tsutakawa (Seattle: Wing Luke Asian Museum, 1994).

Last updated Jan. 15, 2024, 8:46 p.m..

Media

Media