Heart Mountain

| US Gov Name | Heart Mountain Relocation Center |

|---|---|

| Facility Type | Concentration Camp |

| Administrative Agency | War Relocation Authority |

| Location | Cody, Wyoming (44.5167 lat, -109.0500 lng) |

| Date Opened | August 12, 1942 |

| Date Closed | November 10, 1945 |

| Population Description | Held people from Los Angeles, Santa Clara, and San Francisco, California; Yakima, Washington; and Oregon. |

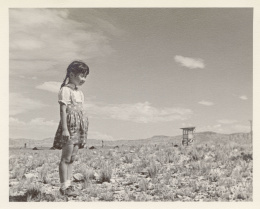

| General Description | Located on 46,000 acres in Park County in northwest Wyoming, 12 miles northwest of Cody, in open sagebrush desert at 4,700 feet of elevation near the Shoshone River. Heart Mountain, 8 miles to the west, creates a dramatic backdrop. Dust storms are common. Winters are severe, with lows dipping to -30 degrees. |

| Peak Population | 10,767 (1943-01-01) |

| National Park Service Info | |

| Other Info | |

Located roughly eight miles away from its namesake, Heart Mountain concentration camp and its inmate population are perhaps best known for their role in fomenting and supporting draft resistance amongst the Nisei during World War II. At maximum capacity, 10,767 inmates from California, Oregon, and Washington were imprisoned at Heart Mountain, including a number who were transferred to Heart Mountain from Jerome concentration camp in Arkansas. [1] Today, Heart Mountain remains a poignant reminder of the innumerable losses incurred due to Executive Order 9066 .

Geography and Prewar History of the Site

Described as "barren" and "pretty spooky" by inmates, and with temperatures thirty degrees below zero during the winter, the location for Heart Mountain concentration camp was chosen not for its beauty or climate, but for its relative isolation from other Wyoming settlements and proximity to fresh water and cheap transportation networks. [2] The land chosen for the camp, which consisted of 46,000 acres between the towns of Cody and Powell, bordering the Shoshone River, was originally part of the Heart Mountain Irrigation Project, which in turn was part of the larger Shoshone Project, both of which were overseen by the Bureau of Reclamation. [3] In 1937 the Bureau of Reclamation began construction of the Heart Mountain Canal eventually utilizing members of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) for labor. Construction was halted when the United States entered WWII and the canal was left incomplete. [4]

Shortly after President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, Wyoming was chosen as a location for a permanent concentration camp that would house thousands of Japanese nationals and Japanese Americans. [5] Although Wyoming's prewar Japanese population was rather small, comprised of only 643 people, the state was not immune to the anti-Asian sentiment that swept through the West Coast. Anti-Asian discrimination was written into Wyoming law through the passage of the 1910 anti-miscegenation law. In addition, beginning in 1939 and continuing throughout the war, law enforcement agencies in Wyoming, responding to a Presidential directive on national defense, initiated programs to safeguard their state from espionage. [6] Local and national anti-Japanese propaganda and hysteria shaped the reactions of some but not all residents to the news that Wyoming would soon host a large Japanese population. Reactions ranged from xenophobia to complacency and from apathy to interest in the potential economic benefits stemming from construction of the camp. Some Wyomingites were particularly interested in the agricultural and industrial labor that internees could provide. However, the general consensus remained that the inmates were not welcome to stay in Wyoming once the war was over. [7]

Establishing the Camp and Moving In

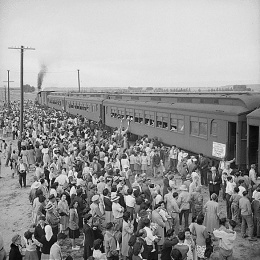

On June 1st 1942, the Bureau of Reclamation officially transferred a portion of the Heart Mountain Irrigation Project, including a number of CCC buildings, to the War Relocation Authority . Construction began shortly after, immediately resulting in a boom in employment and commercial sales for local civilians. The cost of construction was estimated at over 5 million dollars. Around 2,000 individuals were enticed to labor on the camp through offers of overtime pay. Prior experience in construction was unnecessary and advertisements promised, "If you can drive a nail, you can qualify as a carpenter." [8] By August the Army Corps of Engineers and their civilian laborers had constructed 468 barracks and 39 halls and utility buildings. In addition, the campgrounds also included a 150 bed hospital, educational facilities, and pig and chicken farms. [9] In response to the speed of production, laborers "bragged that it took them only 58 minutes to build one apartment barrack," but the lack of worker experience meant that many of the camp buildings were poorly constructed and ill-suited to withstand Wyoming's extreme weather. [10]

In many cases doors and windows were improperly installed and failed to close completely. In addition, gaping cracks between wallboards made both privacy and protection from Wyoming weather difficult. The first inmates arrived at Heart Mountain on August 12, 1942 and were assigned "apartments" within the barracks whose size depended on the number of family members. The inmates worked quickly to improve their new "homes" by hanging spare sheets and celotex from the roof and stuffing cracks with rags and newspapers for warmth and privacy. [11] The units were scantily furnished: each room contained one light, one stove, and army cots for each individual. Therefore, many inmates also took to producing their own furniture and other household items from scrap lumber. (See Arts and crafts in camp .)

Despite these improvements the barracks lacked basic amenities such as running water and cooking facilities. Bathrooms and laundry facilities were communal, differentiated by gender, and located in utility halls. Meals were provided by the camp and were served in mess halls. [12] The communal dining halls proved problematic for a variety of reasons. Many inmates complained about the quality and scarcity of food provided. In addition, youngsters found themselves no longer dependent on their parents for food, clothing, and basic necessities and often ate and socialized with their peers in the mess halls instead of with their parents. As a result nuclear families broke apart. [13]

Life in the Camp

Arrival and Administration

Camp administration was unevenly balanced between Caucasians, who held the high-level authoritative positions; elected Nisei block managers , who served as liaisons between the inmate population and Caucasian administrators; and Issei councilmen. The Nisei and Issei positions were dominated by men; however, Satoye (Ruth) Hashimoto, defied gender norms and served as Block 6 manager at Heart Mountain. [14] Caucasians also dominated leadership positions within the hospital and high school. Both institutions hired Japanese and Caucasians to serve as doctors, nurses, teachers, and teacher aides. War Relocation Authority hiring practices and pay scales however, differed by race, and favored Caucasians. [15] News and information about camp regulations were disseminated by the block managers and through the Heart Mountain Sentinel , the camp newspaper, which published 145 issues from October 14, 1942 to July 28, 1945.

Education and Entertainment

Daily life for young inmates revolved around attending either elementary or secondary school. Classes were conducted by teachers and teaching assistants, the majority of the former being Caucasian. Despite the initial lack of educational materials and complaints about inadequate facilities, the schools provided students with a sense of normalcy and routine during their years in the camp. In particular, Heart Mountain High School, which housed over 1,500 students during its first year of operation, featured a band, the Californians, and a newspaper, Echoes (later renamed the Eagle ), and sponsored social functions and dances. [16] In addition, interscholastic athletic events provided students with the opportunity to socialize with and compete against students from neighboring schools. However, participation in sports did not provide full freedom of movement for the students, as most sporting events were held within the confines of the camp. [17]

Outside of school, religious establishments, the movie theaters, sporting events, scouting, arts and crafts lessons, and cultural activities provided inmates with respite from the banality of camp life. In particular, scouting was very popular with young inmates, many of whom had participated in the organization before incarceration. Although camp administration refused to sponsor Japanese activities, the inmates established cultural clubs and organized celebrations such as the Obon festival . [1]

Employment Opportunities

Countless inmates left behind personal businesses and employment opportunities when they were forcibly moved to Heart Mountain. Upon arrival, some individuals were able to continue to practice their original occupations, albeit for reduced salaries. For example, Bill Hosokawa , a University of Washington journalism major who had worked for English-language newspapers in Asia, was a key player in the establishment of the Heart Mountain Sentinel , and served as editor for the first 52 issues. [18] In addition, Heart Mountain Hospital employed a number of Japanese physicians and nurses as well as more than 600 camp residents for a variety of positions ranging from office clerks to nurse aides and ambulance drivers. (See Medical care in camp .) The majority of these employees, with the exception of the nurses and doctors, had little experience and were paid a mere $12 to $16 a month. [19]

Other inmates found employment by producing vitrified china for the war effort, by seeking jobs in the mess halls or in the school system, by providing the camp with physical labor, or by applying to work beyond the barbed wire. All camp workers were dressed by the Garment Project, which hired inmates to produce uniforms. [20] During the war years, inmates continued the unfinished Board of Reclamation irrigation project, building an additional mile of canal and waterproofing existing canal sections with 850 tons of bentonite. In addition, a number of inmates worked as agricultural laborers in Wyoming, Montana, and Nebraska. [21]

Resistance

Acts of resistance, large and small, were ubiquitous at the Heart Mountain concentration camp. Though perhaps best known for the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee and draft resistance beginning in 1944, a longer standing tradition of protest, both violent and non-violent, developed within the camp.

On September 6, 1942, the strain of working under Caucasian supervisors and the frustration of late food deliveries and thefts drove an inmate cook to physically attack a Caucasian worker with a kitchen knife. The latent antagonism between Caucasian authorities and inmates came to boil again one month later when military police arrested 32 young children for sledding outside of camp boundaries. Although the children were released to their parents, inmates were quick to condemn the treatment of the children by the police. Amidst rising tension the army attempted to recruit volunteer workers to construct a barbed wire fence around the perimeter of the camp. The majority of working-age men went on strike, refusing to participate in the project. They questioned the army's justification for erecting the fence; namely the attempt to keep stray cattle from entering the campgrounds. Three thousand inmates signed a petition "charging that the fence proved that Heart Mountain was indeed a 'concentration camp' and that the evacuees were 'prisoners of war.'" [22]

When the army sought recruits after military service was opened up to Nisei in early 1943, inmate Frank Inouye established the Heart Mountain Congress of American Citizens and demanded the U.S. government re-establish Nisei civil rights, guarantee their citizenship, and eliminate race-based discrimination in the military as a prerequisite to enlistment. As a result, only thirty eight Nisei volunteered for military service from Heart Mountain while 800 Nisei renounced their U.S. citizenship. [23] Later that year, on June 24, 102 hospital employees participated in a walk-out, resulting in a five day strike.

After the War

Inmates began to leave Heart Mountain for the West Coast in January 1945, and the final inmates departed the camp on November 10, 1945. Soon after, farmers established homesteads on the former campgrounds and bid for the camp buildings and agricultural equipment at auction. The former inmates were prevented from homesteading due to an Alien Land Law passed by the Wyoming legislature in 1943 and revoked only in 2001. [24] Although a number of deaths occurred at Heart Mountain, the majority of the deceased were cremated. Around 27 total were buried, most of whom were either the elderly with no known relatives and infants. After the war, seven of the bodies were moved to Crown Hill Cemetery in Powell. [25]

In 1996 the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation, a nonprofit entity dedicated to the historic preservation of Heart Mountain concentration camp, was formed. The Foundation successfully applied for and received National Historical Landmark status for the Heart Mountain site. Today, visitors to Heart Mountain can peruse the newly established Interpretive Learning Center which features permanent and temporary exhibits on internment. The opening of the Center in 2011 coincided with the first annual Heart Mountain Pilgrimage. Visitors can also participate in a 1,000-foot-long walking tour of the remaining camp structures including the Heart Mountain High School, the hospital complex, and barracks living area. Current and ongoing projects include restoring the hospital complex smokestack and improving in-house and web-based educational resources through a 2012 Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant. [26]

For More Information

Bazaldua, Barbara. Boy of Heart Mountain . Camarillo, Calif.: Yabitoon Books, 2010.

Burton, Jeffery F., et al. Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites . Western Archeological and Conservation Center, National Park Service, 2000. Foreword by Testuden Kashima. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002

George and Frank C. Hirahara Photograph Collection, 1943-1945 . Washington State University Library.

Inouye, Mamoru and Grace Schaub. The Heart Mountain Story: Photographs by Hansel Mieth and Otto Hagel of the World War II Internment of Japanese Americans . [Los Gatos, Calif.]: Mamoru Inouye, 1997.

Ishigo, Estelle. Lone Heart Mountain . 1972. Los Angeles: Heart Mountain High School Class of 1947, 1989. Lone Heart Mountain .

Ishizuka, Karen. Something Strong Within . DVD. Frank H. Watase Media Arts Center of the National Museum, 1995.

Mackey, Mike, ed. Remembering Heart Mountain: Essays on Japanese American Internment in Wyoming . Powell, Wyo.: Western History Publications. 1998.

Mackey, Mike. Heart Mountain: Life in Wyoming's Concentration Camp . Powell, Wyo.: Western History Publications, 2008.

Miyagishima, Kara M. 2004. " National Historic Landmark Nomination ."

Nelson, Douglas W. Heart Mountain: The History of an American Concentration Camp . Madison: The State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1976.

Okazaki, Steven. Days of Waiting . VHS. Mouchette Films, 1989.

Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation.

Footnotes

-

↑

1.0

1.1

Jeffery F. Burton et al.

Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites

(Arizona: Western Archeological and Conservation Center, 2000), 129; Mamoru Inouye, "Heart Mountain High School," in

Remembering Heart Mountain: Essays on Japanese American Internment in Wyoming

, ed. Mike Mackey (Powell, Wyo.: Western History Publications, 1998, 86.

Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "ftnt_ref1" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ "A Brief History of the Heart Mountain Relocation Center and the Japanese American Experience," Mike Mackey, accessed May 28th, 2012.

- ↑ Jeffery F. Burton et al. Confinement and Ethnicity , 129.

- ↑ Ibid., 14.

- ↑ Kara M. Miyagishima, "National Historic Landmark Nomination," November 2004, National Park Services, accessed May 26th, 2012, www.nps.gov/nhl/.../wy/Heart%20Mountain%20Nomination.pdf, 20.

- ↑ Ibid., 21-22.

- ↑ Phil Roberts, "Temporarily Sidetracked by Emotionalism: Wyoming Residents Respond to Relocation, " in Remembering Heart Mounysin: Essays on Japanese American Internment in Wyoming , ed. Mike Mackey (Powell, Wyo.: Western History Publications, 1998, 38-39.

- ↑ "National Historic Landmark Nomination," 21-22.

- ↑ Burton, 131 and Inouye and Schaub, 58.

- ↑ "National Historic Landmark Nomination," 21-22.

- ↑ Mike Mackey, Heart Mountain: Life in Wyoming's Concentration Camp (Powell, Wyo.: Western History Publications, 2000), 38-40.

- ↑ Mamoru Inouye and Grace Schaub, The Heart Mountain Story: Photographs by Hansel Mieth and Otto Hagel of the World War II Internment of Japanese Americans ([Los Gatos, Calif.]: Mamoru Inouye, 1997), 22-23.

- ↑ Mackey, 50-51.

- ↑ Inouye and Schaub, 54.

- ↑ "A Brief History of the Heart Mountain Relocation Center and the Japanese American Experience."

- ↑ Inouye, "Heart Mountain High School," 87 and Inouye and Schaub 66, 70.

- ↑ Inouye, "Heart Mountain High School," 84.

- ↑ Bill Hosokawa, "The Sentinel Story," in Remembering Heart Mounysin: Essays on Japanese American Internment in Wyoming , ed. Mike Mackey (Powell, Wyo.: Western History Publications, 1998, 63.

- ↑ Louis Fiset, "The Hospital Strike of June 24, 1943, in Remembering Heart Mounysin: Essays on Japanese American Internment in Wyoming , ed. Mike Mackey (Powell, Wyo.: Western History Publications, 1998, 105.

- ↑ Hosokawa, "The Sentinel Story," 64.

- ↑ Hosokawa. "The Sentinel Story, 56.

- ↑ Frank T. Inouye, "Immediate Origins of the Heart Mountain Draft Resistance Movement," in Remembering Heart Mountain: Essays on Japanese American Internment in Wyoming , ed. Mike Mackey (Wyoming: Western History Publications, 1998, 122-123.

- ↑ Inouye, "Immediate Origins of the Heart Mountain Draft Resistance Movement", 127.

- ↑ Peter Prengaman, "Racist Statutes Under Siege," The Los Angeles Times , September 29, 2002, accessed May 29, 2012, http://articles.latimes.com/2002/sep/29/news/adna-racist29 .

- ↑ Inouye and Schaub, 80.

- ↑ "Dedicated to Sharing the Lessons of History," Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation, accessed May 29, 2012, and Martin Kidston, "Forensic Analysis May Help Save Heart Mountain Smokestack," Billings Gazette , March 29, 2012, accessed May 29, 2012, http://billingsgazette.com/news/state-and-regional/wyoming/forensic-analysis-may-help-save-heart-mountain-smokestack/article_3eabdf9a-97e3-56e2-b571-6903905dc1c3.html .

Last updated Feb. 12, 2024, 10:57 p.m..

Media

Media