Military Intelligence Service

Under a shroud of secrecy and with the backing of the United States War Department, the Military Intelligence Service (MIS) trained and graduated nearly 6,000 linguists—the majority of whom were Japanese Americans. Due to the security-classified nature of their activities, Nisei members of the MIS never received as much publicity as their counterparts in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team (RTC) and 100th Infantry Battalion . They ultimately played a decisive role in the victory of American forces over Japan in the Pacific. They were among the first soldiers to arrive in Japan after its surrender, and they became some of the first American observers to witness the destructive effects of the atomic bombs that had been dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The Nisei later served in important positions in the occupation of Japan and more than seventy MIS linguists provided translation and interpreter services for the war crimes trials held in Japan, China, the Philippines, French Indochina, and the East Indies. As Japanese Americans, these linguists turned out to be instrumental in bridging cultural and linguistic differences and helped to establish the foundations for postwar relations between Japan and the United States. [1]

Role of the MIS in World War II

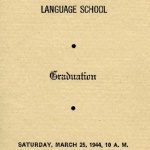

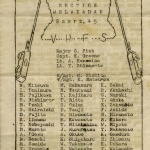

During World War II, MIS graduates took on active service in every combat theater and engaged in every major battle launched against Japanese military forces. According to Major General Charles Willoughby, G2 Intelligence Chief for General Douglas MacArthur, these Nisei "shortened the Pacific war by two years." [2] They served with the United States Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force as well as with British, Australian, New Zealand, Canadian, Chinese, and Indian combat units fighting the Japanese. Trained as interrogators, interpreters, translators, radio announcers, and propaganda writers at the Military Intelligence Service Language School at the Presidio in San Francisco, and at Camp Savage and Fort Snelling in Minnesota, MIS graduates came to be considered the "eyes and ears" of American and Allied Forces in the war against Japan. By September 1945, they had translated 18,000 captured enemy documents, printed 16,000 propaganda leaflets, and interrogated more than 10,000 Japanese prisoners of war. [3] These men faced some of the most dangerous situations during the war, often being placed on the front lines of battle against the Japanese while simultaneously trying to avoid "friendly fire" from American soldiers who could not distinguish them from enemy Japanese. According to John Aiso , an MIS veteran, "We may have been the only soldiers in history to have bodyguards to protect us from our own forces in combat zones so we would not be mistaken for the enemy." [4] More than one MIS soldier became a casualty from "friendly fire," and many MIS personnel had to ensure that Caucasian soldiers who could vouch for their loyalty accompanied them into battle.

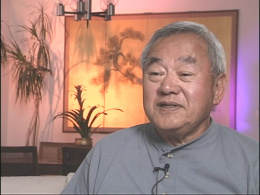

Besides the constant danger of "friendly fire," the Nisei were well aware that imperial forces considered them to be Japanese nationals, and capture meant certain execution as traitors. Their identities doubled the dangers they faced in battle from both Japanese and American soldiers, both of whom perceived them as the enemy. Unlike the Navajo Code Talkers also utilized by the American military, these linguists who operated in the Pacific were confronted by the very real possibility of encountering and fighting against friends, acquaintances, and family members. Many of them had close personal ties to Japan or had attended school in Japan. Throughout the war, many had unexpected meetings and spontaneous reunions with former teachers, classmates, and family members, emphasizing the complicated and personal nature of war for the men of the MIS, particularly as combat came closer to Japan. Takejiro Higa, for example, wondered what would happen if "I meet somebody I know, or my relative, my classmate" in battle or in the prisoner of war (POW) camps. [5] This was Higa's biggest concern—one that weighed heavily on his mind since contact between siblings or former classmates fighting on opposing sides took place fairly regularly. During the Battle of Okinawa, Higa unexpectedly encountered two of his childhood friends as well as his seventh and eighth grade teacher, Shunso Nakamura, who was "dumbstruck, never dreaming he would see one of his former students with the invading forces." [6]

The war took on a very personal element as these soldiers also encountered civilian populations with familiar faces and family ties. One of the most dangerous yet valuable services the men of the MIS provided in Okinawa was to persuade people who were hiding in the numerous deep caves on the island to surrender. If they did not, the Americans would dynamite the caves to prevent Japanese soldiers from using them as hideouts. During the Battle of Okinawa, the men of Okinawan descent, such as Seiyu Higashi, Jiro Arakaki, and Shiney Gima, would often ask for permission to search for their parents or relatives in the mountains or civilian compounds.

Throughout the war these linguists were often present at the most critical encounters—both military and diplomatic—between Japanese and American forces. MIS personnel had the greatest impact in the Pacific Theater where they participated in every major battle and campaign against Japan. MIS soldiers served as undercover agents in the Philippines, fought behind enemy lines with Merrill’s Marauders in Burma, experienced jungle warfare in New Guinea, landed with the Marines on the beaches of Iwo Jima, and crawled into the caves of Saipan to persuade suicidal enemy forces to surrender. Throughout their experiences, they confronted their dual identity as American citizens of Japanese ethnicity, fighting to prove their loyalty against the country of their parents. Numerous soldiers had family members within the incarceration camps, while others knew of relatives still residing in Japan. When the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima on August 6 and on Nagasaki on August 9, 1945, all but ending the war, many Nisei experienced mixed emotions, as many had family members still living in these two Japanese cities.

The Occupation of Japan

According to Nisei veteran Hideo Uto, the "tremendous task of occupying the Japanese homeland" fell upon linguists skilled in communicating in Japanese, including second-generation Japanese Americans who were put to work in all phases of the occupation program and in all parts of Japan. [7] During the occupation of Japan, Nisei interpreters worked closely with both the Marine officers in charge of restoring Nagasaki and Nagasaki City and prefectural officials. In addition to issues related to public welfare and the rebuilding of cities, they were also responsible for the demobilization of Japanese military personnel from various overseas posts in Siberia.

Another important concern for American forces was the arrest and prosecution of Japan's military leaders—a task which also involved Nisei personnel. Many Nisei participated in the prosecution of the individuals housed in Sugamo Prison during the war trials that began in December 1945 and lasted until 1948. [8] More than seventy linguists, most of them members of the MIS, provided translation services for the war crimes tribunals and served as the interpreters for the trials held in Japan, China, the Philippines, French Indochina, and the East Indies. In addition to working directly with Japanese and Japanese officials, many Nisei officers were assigned as language aides and cultural liaisons to key General Headquarters (GHQ) officers.

Administrative matters also constituted an important concern for American forces as a new Japanese constitution needed to be written. MIS graduate George Koshi became intimately involved in this historic undertaking, which forever renounced war as a "sovereign right of the nation." [9] The new constitution also forbade the existence of a Japanese military. To maintain internal security, the constitution provided for a national Police Reserve force, which came about with the assistance of MIS personnel such as Raymond Aka. Further, members of the MIS, including Shiro Tokuno and Shigehara Takahashi, participated in the implementation of the compulsory agrarian land law throughout Japan in October 1946. This revolutionary piece of legislation remanded nearly six million acres of farmland to individual farmers and eliminated the prewar rural domination by large landowners.

During this period of upheaval and reorganization in Japan, two organizations staffed by MIS personnel proved critical to maintaining order. The first, the Civil Censorship Detachment (CCD), extracted civil intelligence information from various mass media sources in Japan to monitor and ensure the orderly implementation of occupation policies originating from MacArthur's headquarters in Tokyo. The CCD was responsible for censoring all forms of Japanese communication. The other important organization in the occupation was the Counter Intelligence Corps, or CIC, which had offices in all major Japanese cities. Several hundred Nisei special agents and investigators worked throughout Japan to detect and prevent subversive activities.

According to the dominant literature, the efforts made by Nisei of the MIS during the occupation of Japan contributed to the rebuilding of Japan through the development of personal relationships between Japanese and Americans. As members of both cultures, they exploited their dual identity to bridge cultural differences and create understanding and reconciliation between the two nations. Many scholars as well as veterans themselves have argued that their loyalty arguably belonged to both Japan and the United States: while they worked for an American military victory and were active during the occupation of Japan, they also possessed a deep and abiding interest in the welfare of the Japanese people during the rebuilding of Japan. Other scholars like Eiichiro Azuma offer a more critical perspective of the actions of the MIS during the occupation of Japan as Nisei soldiers were also used as direct enforcers of United States military domination against Japanese nationals. Thus, to protect their reputation of uncompromised loyalty, some Nisei soldiers also behaved in a most "undemocratic" manner to Japanese citizens as they served as "middlemen" between occupying forces and the general population. [10]

Both perspectives, however, recognize the challenges facing Nisei soldiers of the MIS who held American citizenship yet possessed ethnic and cultural ties to Japan. As "cultural brokers" between Japan and America, their dualistic identities posed a challenge both in the United States and Japan as they were identified as cultural liaisons but were never really embraced by both sides. The nebulous position occupied by members of the MIS enabled these soldiers to engage in a wide variety of activities and behaviors that were both celebrated and criticized by American and Japanese officials during and after the war. As such, a nuanced perspective of the role of the MIS is necessary to understand the diversity of their experiences and actions particularly during the occupation of Japan.

For More Information

Americans of Japanese Ancestry and Their Contributions to the Second World War . University of Hawai'i at Mānoa Hamilton Library (n.p., n.d.,) microfilm, 1972.

Azuma, Eiichiro. "Brokering Race, Culture, and Citizenship: Japanese Americans in Occupied Japan and Postwar National Inclusion." The Journal of American-East Asian Relations 16:3 (fall 2009): 183-211.

Go for Broke National Education Center. "History: Military Intelligence Service (MIS)." http://www.goforbroke.org/history/history_historical_veterans_mis.asp .

Harrington, Joseph D. Yankee Samurai: The Secret Role of Nisei in America's Pacific Victory . Detroit, Michigan: Pettigrew Enterprises, 1979.

Hellinger, Charles. "The Secrets Come Out for Nisei Soldiers: Japanese-American Role in Military Intelligence Service Finally Told." The Los Angeles Times, July 20, 1982, Part V, 1.

Ichinokuchi, Tad and Daniel Aiso, eds. John Aiso and the M.I.S.: Japanese-American Soldiers in the Military Intelligence Service, World War II . Los Angeles: The Club, 1988.

Japanese American Veterans Association. "Military Intelligence Service." http://www.javadc.org/index3.htm .

Kikuchi, Yuki. The Pacific War of the Nisei in Hawai'i . Translated by Yoko Hayashi Horiuchi. Pearl City, Hawai'i: n.p., 1999.

Military Intelligence Service Veterans Club of Hawai'i. Secret Valor: M.I.S. Personnel, World War II, Pacific Theater, Pre-Pearl Harbor to Sept. 8, 1951: 50th Anniversary Reunion, July 8-10, 1993 Military Intelligence Service Veterans Club of Hawai'i . Honolulu: Military Intelligence Service Veterans of Hawai'i, 1993.

Nakasone, Edwin M. The Nisei Soldier: Historical Essays on World War II and the Korean War . White Bear Lake, MN: J-Press, 1999.

National Japanese American Historical Society. http://www.njahs.org/ .

The Pacific War and Peace: Americans of Japanese Ancestry in Military Intelligence Service 1941 to 1952 . San Francisco: Military Intelligence Service Association of Northern California and the National Japanese American Historical Society, 1991.

Takemae, Eiji. The Allied Occupation of Japan . New York: The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc., 2002.

Tamura, Linda. Nisei Soldiers Break Their Silence: Coming Home to Hood River . Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2012.

A Tradition of Honor . DVD. Produced by Craig Yahata and David Yoneshige. Go For Broke Educational Foundation in Association with Hanashi Oral History Program, 2003.

Tsai, Michael. "Sohei Yamate: Hawai'i Nisei Recalls Tojo's Imprisonment at Sugamo Prison." The Hawai'i Herald 14, 14 (1993): A-28.

Uto, Hideo. "The Nisei in Japan: Relationships Between Nisei and Japanese." Social Process in Hawai'i XII (August 1948): 43.

Footnotes

- ↑ Research for this article was supported by a grant from the Hawai‘i Council for the Humanities .

- ↑ Tad Ichinokuchi and Daniel Aiso, eds., John Aiso and the M.I.S.: Japanese-American Soldiers in the Military Intelligence Service, World War II (Los Angeles: The Club, 1988), 177.

- ↑ Eiji Takemae, The Allied Occupation of Japan (New York: The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc., 2002), 21.

- ↑ Aiso, 177.

- ↑ A Tradition of Honor , prod. Craig Yahata and David Yoneshige (Go For Broke Educational Foundation in Association with Hanashi Oral History Program, DVD, 2003).

- ↑ Military Intelligence Service Veterans Club of Hawai'i, Secret Valor: M.I.S. Personnel, World War II, Pacific Theater, Pre-Pearl Harbor to Sept. 8, 1951: 50th Anniversary Reunion, July 8–10, 1993 Military Intelligence Service Veterans Club of Hawai'i (Honolulu: Military Intelligence Service Veterans of Hawai'i, 1993), 101.

- ↑ Hideo Uto, "The Nisei in Japan: Relationships Between Nisei and Japanese," Social Process in Hawai'i XII (August 1948): 43.

- ↑ Michael Tsai, "Sohei Yamate: Hawai'i Nisei Recalls Tojo's Imprisonment at Sugamo Prison," The Hawai'i Herald 14, 14 (1993): A-28.

- ↑ Koshi also served as defense counsel during the war crimes investigations and trials held from December 1945 to mid-1948 in Tokyo and Yokohama. The Pacific War and Peace: Americans of Japanese Ancestry in Military Intelligence Service 1941 to 1952 (San Francisco: Military Intelligence Service Association of Northern California and the National Japanese American Historical Society, 1991), 72.

- ↑ Eiichiro Azuma, "Brokering Race, Culture, and Citizenship: Japanese Americans in Occupied Japan and Postwar National Inclusion," The Journal of American-East Asian Relations , 16:3 (fall 2009): 187.

Last updated Oct. 16, 2020, 5:54 p.m..

Media

Media